Lehman Brothers’ collapse led to the mother of all modern recessions — until now

Summary

On Sept. 15, 2008, the collapse of the Lehman Brothers investment bank sent shock waves around the world and turned problems in the US property market into a global financial crisis.

The crisis of 2008-09 brought unprecedented change — and fear — to the world economy. Government intervention, not least by China, averted catastrophe, but left a legacy of soaring debt. In the current economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the worry is that a more divided world will be unable to apply the same remedies.

DUBAI: In his epic account of the 2008 global financial crisis, “Too Big to Fail,” Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote: “Never have I witnessed such fundamental and dramatic changes in business paradigms and the spectacular self-destruction of storied institutions.”

What superlatives will Sorkin use when it comes to tell the story of the current crisis, which threatens to eclipse the economic damage of just over a decade ago by a multiple factor?

The events of the global financial crisis (GFC) seemed at the time so utterly transformational that it was impossible to imagine anything similar happening twice in a lifetime.

At the beginning of 2007, the world appeared on an ever-improving path, with rising economic growth, stock markets and personal living standards. The financial industry, especially in real estate, was an eternal wealth-creating machine.

By the end of 2009, stock markets had collapsed, economies around the world were in steep recession, individuals — the ones who had not gone bankrupt or lost their homes — had taken such a hit to their standards of living that many just gave up. There was a sharp rise in reported suicides.

In the Middle East in 2007, oil prices — as ever the determining factor in regional economies — had been on the rise since the turn of the millennium, driven by the global economic boom.

Saudi Arabia was benefiting from that revenue and was thinking about diversifying its economy away from oil. Membership of the World Trade Organization a couple of years before had given the Kingdom a more extrovert perspective, perhaps with one eye on the glittering example of Dubai, a booming economic role model for the Arab world.

Fast forward two years, and the oil price had collapsed, losing $100 per barrel in value in the second half of 2008, diversification plans were on hold as policymakers made survival their priority, and Dubai was on the brink of an existential threat to its debt-fueled business model.

“It was the financial equivalent of 9/11,” one commentator said at the time.

'Asia tumbled first on the news yesterday, followed by the Middle East, Russia and then Europe before the shock wave hit the North and South American markets.’

From a story by Khalil Hanware on Arab News’ front page, Sept. 16, 2008

Like that attack a few years earlier, the GFC had its “ground zero” in New York. The “masters of the universe” on Wall Street had recovered from the blips of the Al-Qaeda attacks and the dot-com bust, and had piles of other people’s capital to put to invest.

The American dream — a home, a couple of cars, maybe even a boat somewhere — was within reach. All bought on credit. And Wall Street had come up with a revolutionary method of financing.

All that credit could be bundled into “collateralized debt obligation” (CDO) and sold as investable instruments that could be traded among the big firms, which were, of course, “too big to fail.”

But by the summer of 2007, what was termed the “subprime” mortgage market was in serious trouble. The loans bundled together in CDOs were worth only as much as the most toxic mortgage in the basket.

The first sign that this was anything more than a threat to the US property market came when Merrill Lynch, one of Wall Street’s “blue blood” banks, suffered a shocking $5.5 billion loss.

The stock market caught the contagion, with shares prices falling 50 percent over a few months. The “mom and pop” businesses of Main Street USA found their capital and pensions wiped out in a Wall Street bloodbath.

Key Dates

-

1Merrill Lynch, one of Wall Street’s leading investment banks, records a big loss, evidence that the crisis in US real estate markets is infecting the entire financial system. The bank is eventually sold to Bank of America to save it from bankruptcy.

-

2The Dow Jones Industrial Average index hits 7,000 points, representing a 50 percent loss over the previous four months. The crisis is in full swing on the world’s biggest stock market.

-

3The collapse of Lehman Brothers, one of Wall Street’s ‘blue blood’ banks, sends shock waves around the world and turns the problems in the US property market into a global financial crisis. One observer calls it the ‘financial equivalent of 9/11.’

-

4The World Bank warns that global economic activity will fall by almost 3 percent over the years, the first downturn since World War II. The financial crisis is affecting the global economy and threatening a second ‘Great Depression.’

-

5Dubai World, creator of the Palm Jumeirah and perhaps the best known of the government-owned conglomerates that made up ‘Dubai Inc,’ says that it will be unable to repay up to $63 billion of debts. Dubai eventually renegotiates its liabilities to international banks with $20 billion of financial help from Abu Dhabi.

-

6Signifying an end to the global recession, crude oil rises above $130 a barrel, its highest point since the boom before the financial crisis. Oil trades consistently above $100 per barrel until the over-supply shock in summer of 2014.

A financial nadir was reached when Lehman Brothers, a 150-year-old pillar of the US financial system, filed for bankruptcy. Despite the hundreds of billions of dollars US federal authorities had spent on propping up the system, it turns out nobody was too big to fail.

The global financial system was dangerously close to freezing up altogether, with credit increasingly difficult to obtain. Massive government intervention, not least at the emergency G20 meetings in 2008 and 2009, kept the wheels just about moving.

But the global economy was feeling the shock, and with it the Middle East, which had survived the credit crisis relatively well, thanks mainly to government austerity measures and big financial reserves. Vital oil prices rose quickly as the global economic situation improved on the back of an economic stimulus package by China.

The regional exception was Dubai. With minimal oil reserves, its exuberant growth had been fueled by debt and, by late 2009, it found it could not service many of those liabilities. Dubai World, one of the government companies at the forefront of extravagant projects such as the Palm Jumeirah, told creditors it was seeking a “standstill” on debt repayments while it renegotiated its loans.

The year-long negotiations were fraught, but in the end Dubai’s creditors stood by it, as did the oil-rich government of Abu Dhabi, which provided $20 billion as a life-saving act of fraternal support. “Standing still, but still standing” was how The Economist magazine described it.

Despite the hundreds of billions of dollars US federal authorities had spent on propping up the system, it turns out nobody was too big to fail.

Frank Kane

But in many ways, the Dubai experience encapsulates the global situation since the GFC, and explains why the current crisis could get even more serious. The emirate has restructured and extended its debts, even repaid some, while taking out others. Dubai’s aggregate level of indebtedness is still roughly the same as it was in 2010, according to the IMF.

The world has also continued its debt spree. Total global indebtedness is estimated at $250 trillion, three times what it was in 2008. The IMF in its most recent forecast said that the economic effects of the pandemic crisis could be the worst since the 1930s Depression.

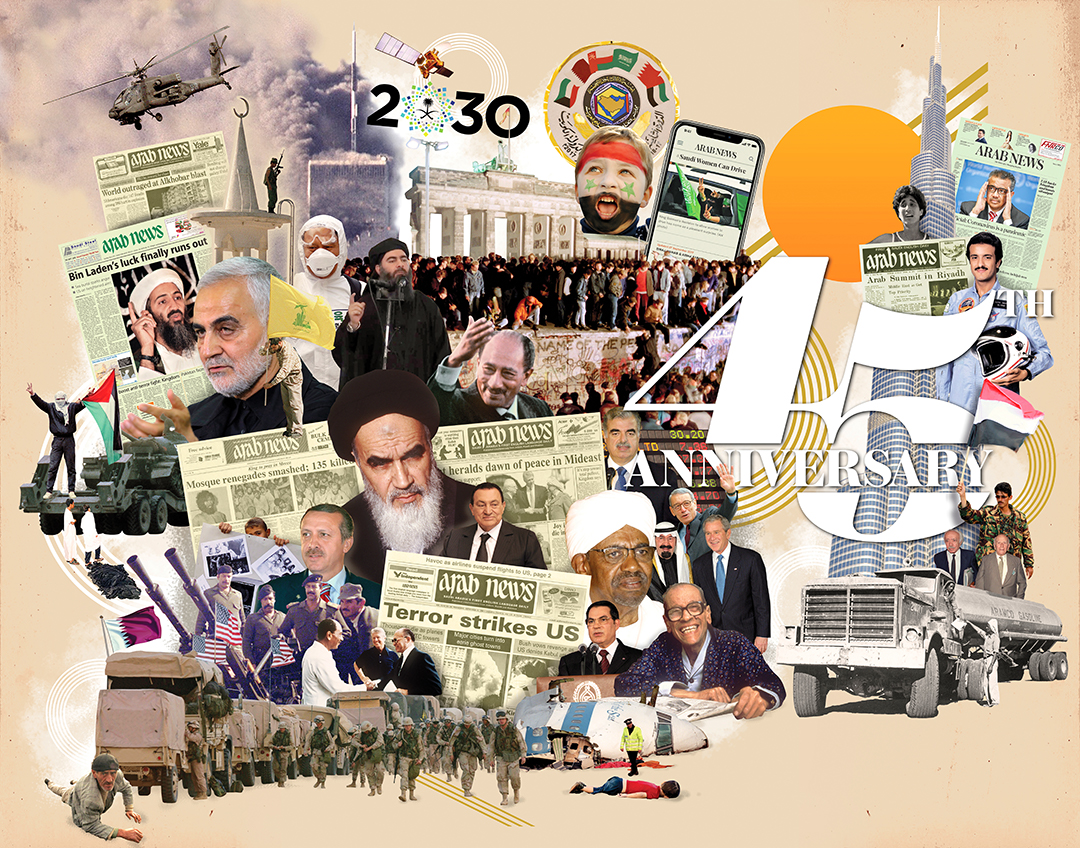

A page from the Arab News archive showing the news on Sept. 16, 2008.

Apart from the debt factor, the coronavirus crisis is different from the GFC in other ways, none of them encouraging. There is the immediate threat to life, of course, and the worry that China does not have the capacity to pull off another rescue act. There is also the fear that global institutions are not as capable now as they were in 2008 of adopting effective measures to avert catastrophe.

“The world economy is now collapsing,” ran a headline in the Financial Times recently. Sorkin will have to consult the superlatives dictionary for his next book.

- Frank Kane has reported on every financial crisis since 1987 for some of the world’s leading newspaper titles.