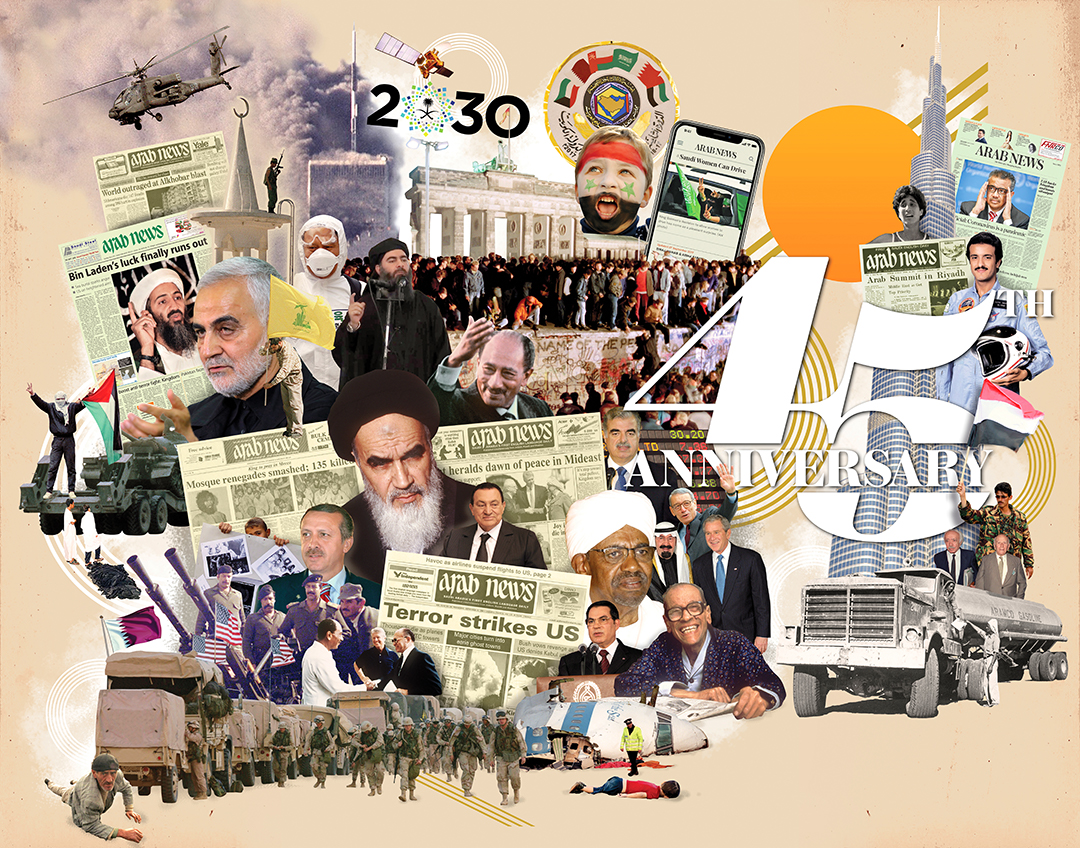

Long a taboo subject, the full fallout from Juhayman Al-Otaibi’s attack on the Grand Mosque only came to light decades later

Summary

On Nov. 20, 1979, the first day of the Islamic year of 1400, tens of thousands of worshippers converged on the Grand Mosque in Makkah for the once-in-a-lifetime chance to experience the dawning of a new century in Islam’s holiest place.

But within moments of the completion of fajr, the first prayer of the day, joy turned to horror as gunshots rang out across the courtyard. The Grand Mosque, Islam’s holiest sanctuary, had been seized by a group of 260 heavily armed religious fanatics. It was the beginning of a bloody siege that would last two weeks and, coming as it did in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, would lead to a setback in modernization from which Saudi society is only now recovering.

JEDDAH: Shrouded in secrecy and rarely discussed, the 1979 siege of Makkah nevertheless had severe repercussions for Saudi Arabia, with many of my generation growing up largely unaware of the high price we were paying for the extremist attack.

Key Dates

-

1

A group of religious extremists led by Juhayman Al-Otaibi, a former corporal in the Saudi National Guard, seizes the Grand Mosque in Makkah.

-

2

For the first time in centuries, no Friday sermon is preached from the Grand Mosque. The ulema issues a fatwa authorizing force against the militants on holy ground if they reject an opportunity “to surrender and lay down their arms.”

-

3

After hours of bloody fighting, troops retake the Safa-Marwa gallery, driving Al-Otaibi and the surviving insurgents into the warren of interconnected rooms under the mosque.

-

4

At the start of the final assault, gas is dropped into the basement maze through holes drilled in the floor of the courtyard. This triggers 18 hours of bitter fighting before the final stronghold is breached, 15 days after the siege began.

-

5

King Khalid addresses the nation, thanking Allah for His support in crushing the “seditious act of sacrilege.”

-

6

Call to noon prayer brings thousands of worshippers to the mosque for the first time in three weeks. Many have camped out all night for a historic ceremony that is broadcast to other Islamic states.

-

7

Interior Ministry announces that 63 captured extremists have been executed in eight different cities. Al-Otaibi is among the 15 executed in Makkah.

Ringing in the new year with early morning prayers, the worshippers on their once-in-a-life-time pilgrimage were shocked to hear gunfire and then a demand to pledge allegiance to the so-called Mahdi. This figure is referred to as the Messiah in several passages of the Hadith (Prophet’s sayings), although Islamic scholars are divided over the meaning.

It wasn’t until I was 16 and in my junior year of high school in 2002 that I first heard of the siege. On the 23rd anniversary of the attack, I opened the Friday edition of the local newspaper Okaz and saw two pages featuring graphic black-and-white images of a mosque with smoke pouring from its minaret, and a photograph of a man with piercing eyes and a disheveled look. It was then that I learned the name of the extremist behind the horrendous attack: Juhayman Al-Otaibi. Curious by nature, my interest began to grow.

For years there was little information to be found in Saudi Arabia about the seizure of the Grand Mosque. However, when the Internet was introduced, search engines provided me with the means to know more — but still it wasn’t enough.

It was only in September 2019 that a highly anticipated interview with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on CBS’s “60 Minutes” shed more light on the matter. Speaking to Norah O’Donnell, the crown prince explained how two events in 1979, the Iranian Revolution and the Grand Mosque siege, halted progress in Saudi Arabia.

“After 1979, it’s true, we were victims, especially my generation that suffered from this a great deal,” said the crown prince. “We were living a very normal life like the rest of the Gulf countries. Women were driving cars, there were movie theaters in Saudi Arabia.”

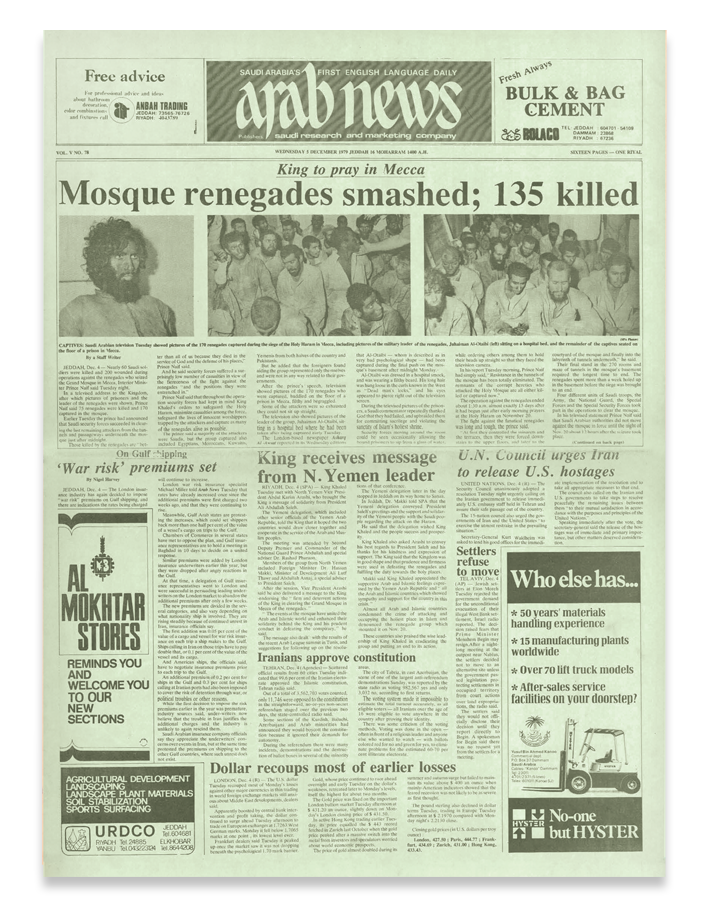

“Television showed pictures of the 170 renegades who were captured, huddled on the floor of a prison in Makkah, filthy and bedraggled.”

From a staff story on Arab News’ front page, Dec. 5, 1979

I knew this interview would encourage others to re-examine this event. In 2019, on the 40th anniversary of the attack, I was working at Arab News and was able to carry out a proper investigation as lead reporter on an online Deep Dive that looked at the siege in detail. The special report was a way of answering all the questions still on my mind.

As our team reported, Al-Otaibi was among 260 heavily armed religious fanatics who seized the Grand Mosque and sparked a standoff with Saudi forces that lasted for more than two weeks. Well trained and ruthless, the extremists launched the siege by locking the mosque’s gates, trapping an estimated 100,000 worshippers inside for more than four hours.

Over the broadcast system normally used for prayers, they told those inside that the so-called Mahdi, Al-Otaibi’s brother-in-law Mohammed Al-Qahtani, was there to rid the world of evil and return Islam to its true path. The Kingdom, prospering and developing into a modern nation, was deemed evil by Al-Otaibi, Al-Qahtani and his followers.

Thus began one of the bloodiest battles the Holy Mosque of Makkah has seen in centuries. The unbelievable events that unfolded are still difficult to believe, as many of our sources recounted, including Prince Turki Al-Faisal, head of Saudi intelligence at the time; a pilot from the Royal Saudi Air Force who flew over the mosque; and the grandson of a hostage who escaped with many others through star-shaped windows in the Safa-Marwa gallery.

A page from the Arab News archive from Dec. 5, 1979.

While I was not alive to witness it, the siege of Makkah changed the psyche of Saudi society, with repercussions for many in my generation.

Rawan Radwan

For the first few days, the Saudi forces pushed into the mosque and a battle ensued. The events played out like a scene from an action movie, with the Saudi forces forcing the religious extremists back. Faced with the final assault, Al-Otaibi and his followers barricaded themselves in the basement, making it more difficult for the Saudi forces to reach them.

During the battle, Al-Qahtani was killed, along with more than 100 extremists. In the final stages, Saudi forces launched gas before they entered the labyrinth of tunnels under the mosque, where they captured Al-Otaibi and his remaining followers, including women and children.

When the siege finally came to an end, the mosque’s walls were riddled with bullets, and more than 25 innocent worshippers lay dead. More than 450 soldiers were wounded, and 127 lost their lives. In Al-Otaibi’s group, 117 were killed and hundreds arrested, with 63 later executed. In January 1980, Al-Otaibi was executed along with 14 of his followers in Makkah.

In an Arab News report from Dec. 5, 1979, entitled “Lessons of Makkah,” the writer concluded: “It is safe to say that the fact that they chose the Holy Kaaba for their attack is prime proof of the false nature of their call. We can only describe them as a gang of brainwashed religious fanatics, trained to believe in society’s deviation from Islam in the existence of their ‘expected Mahdi’ who they claim would ‘bring justice to the world.’”

The aftermath was grave. While I was not alive to witness it, the siege of Makkah changed the psyche of Saudi society, with repercussions for many in my generation. In the wake of the siege, the religious police were empowered, and the Kingdom’s steady modernization was put to a halt. School curriculums, everyday activities and social norms were drastically changed.

Although Saudi Arabia — religiously conservative, yet peaceful — rejected Al-Otaibi’s violent call for the “return to the true religion of Islam,” many felt pressured to conform to changes taking place in their communities.

The search for answers never stopped. It was only when Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman vowed to return the country to “moderate Islam” 2017 and referred to pre-1979 Saudi Arabia in his CBS interview, that it began to make sense.

- Rawan Radwan, regional correspondent for Arab News based in Jeddah, has a keen interest in Saudi history. For more than 15 years, she has carried out research into the siege of Makkah, and for the 40th anniversary in 2019, she was lead reporter on an Arab News Deep Dive that recreated the event in detail