The dismantling of the Soviet bloc symbol was a sign that the Cold War’s days were numbered

Summary

On Nov. 9, 1989, jubilant crowds on both sides of the East-West border began tearing down the Berlin Wall, the hated symbol of the Cold War that had divided Berlin and Berliners for almost three decades.

The wall had been built in 1961 by the puppet communist state installed by the USSR after World War II in occupied East Germany. For 28 years, it stood as the physical manifestation of British wartime leader Winston Churchill’s rhetorical prediction in 1946 that the Soviets were intent on drawing “an iron curtain” across Europe.

Over the years, thousands of East Berliners risked their lives, and hundreds lost them, attempting to defect to West Berlin. In the end, the collapse of the wall, toppled by popular pressure as the communist states of Eastern Europe suddenly began to fall, symbolized the collapse of communism itself. In 1991, just one year after East and West Berlin were reunited, the USSR itself imploded.

DUBAI: I have a piece of the Berlin Wall. Don’t we all? If every “piece of the Berlin Wall” were genuine, the edifice itself would have encircled the globe three times with enough left over to separate the US from Mexico. Nevertheless, no one will persuade me that my chunk of crumbling concrete, stained with the fading paint of a long forgotten graffiti artist, is anything other than the real thing.

Of less dubious provenance are my East German border guard’s fur hat and lapel pin, purchased at an impromptu trestle-table market set up by enterprising Berliners near the Brandenburg Gate. These have a back story.

When it became clear that the wall would fall, many of the communist guards (not the most popular of fellows, having been responsible for the deaths of up to 200 of their fellow Germans in the previous 30 years) fled down the broad Unter den Linden avenue, casting off their uniforms for fear of being identified. Ironically, many were subsequently detained, betrayed by the fact that in the unforgiving chill of a German November, they were wearing only underwear.

In September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain described Adolf Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland as a “quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing.” A year later, Britain was at war with Nazi Germany.

In June 1961, East German leader Walter Ulbricht declared: “No one has the intention of erecting a wall.” It was the first clue that this was precisely the intention.

Ross Anderson

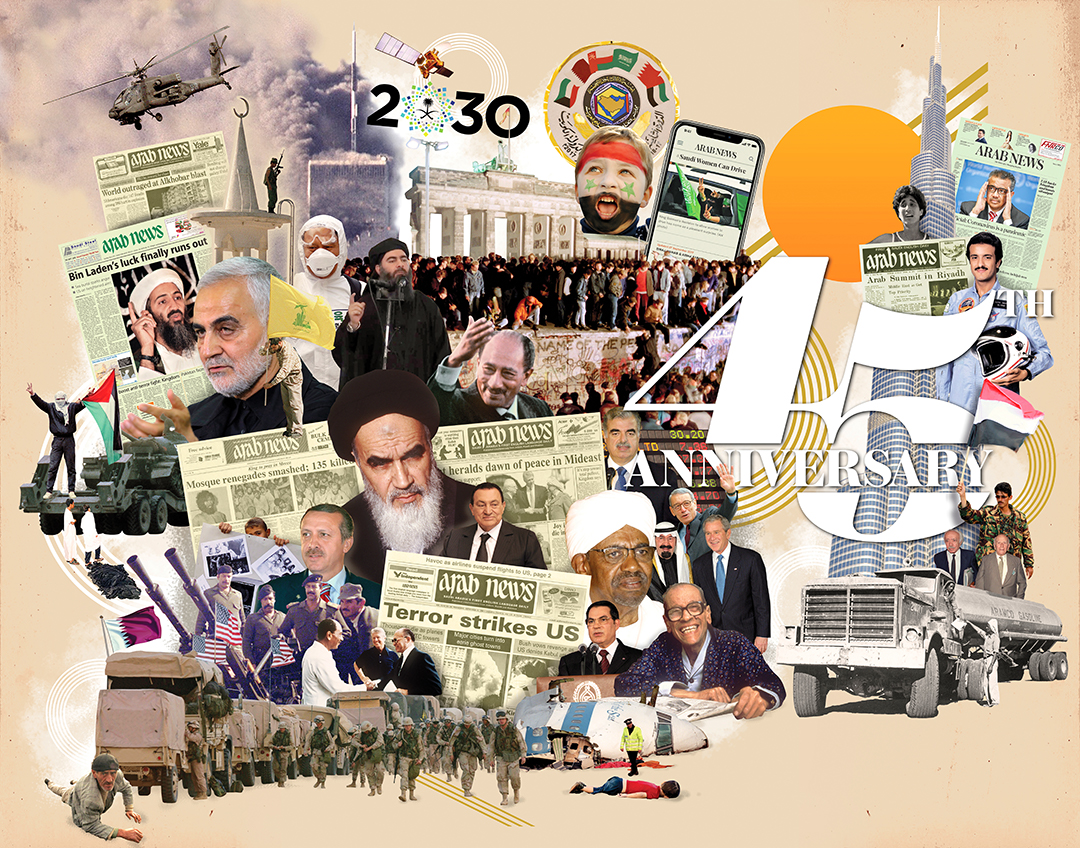

On Nov. 11, 1989, no such insular myopia afflicted Arab News, which devoted a large chunk of its front page to events in Germany — “a far away country,” certainly, but one where the Cold War played out every day in a single city, with profound implications for the Middle East and the whole world.

If the fall of the wall was inevitable, so too was its construction, which began in August 1961 amid the division of Europe after World War II. Within four years of the conflict ending, the Soviet Union had installed puppet communist governments throughout Eastern Europe, including the new German Democratic Republic, or East Germany.

The Western allies set up a parallel administration in areas they controlled, which became the Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany. The frontline of this Cold War was West Berlin, a Western enclave surrounded by the communist East.

It was never going to work. As the West prospered, thanks to an influx of Marshall Plan funds from America, the East stagnated, stifled by economic mismanagement and a sclerotic bureaucracy.

Tensions simmered for 12 years, exacerbated by the original “brain drain” of the young, the bright and the ambitious from East to West. In June 1961, East German leader Walter Ulbricht declared: “No one has the intention of erecting a wall.” It was the first clue that this was precisely the intention.

East German troops and police closed the border at midnight on Aug. 12, and the following day — still known in Germany as Barbed Wire Sunday — they began sealing off West Berlin with the beginnings of the wall. By the time it was complete — it went through four iterations, in 1961, 1962, 1965 and 1975 — the wall was more than 150 km long and 4 meters high, with 186 watchtowers, more than 250 dog runs and 20 bunkers.

Key Dates

-

1Walter Ulbricht, East German Communist Party leader, orders construction of a wall to separate East and West Berlin.

-

2Construction of the Berlin Wall begins.

-

3In a speech in West Berlin, US President John F. Kennedy says: “Today in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’.”

-

4US President Ronald Reagan, visiting West Berlin, calls on Mikhail Gorbachev, leader of the USSR, to “tear down this wall.”

-

5The East German government lifts travel restrictions, and crowds begin dismantling the wall.

-

6West and East Germany are reunified as the Federal Republic of Germany.

-

7Gorbachev resigns as president of the Soviet Union, replaced by Boris Yeltsin as president of the new state of Russia.

The Soviet bloc maintained for 40 years that the purpose of the wall was not to keep its people in, but to keep the “fascist West” out — a claim somewhat diluted by the facts. Between 1961 and 1989, more than 5,000 East Germans defeated the wall — whether by tunneling under it, flying over it or simply driving straight through it. The number who traveled in the opposite direction is not thought to be large.

The wall, and all it represented, were a red rag to successive US presidents. Less than two years after its construction, John F. Kennedy told a crowd of 450,000 in West Berlin: “All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin, and therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words, ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’” Pedants (and bakers) pointed out that he had declared himself to be a jam-filled German pastry, but the point was made.

Twenty-four years later, in a speech at the Brandenburg Gate, Ronald Reagan directly challenged Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev: “If you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe … Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Reagan did not have long to wait. As he spoke, the Soviet dominoes were beginning to tumble. The communist government in Poland was booted out of office. Hungary dismantled the fence along its border with Austria, and 13,000 East Germans took that route to the West. There was unrest in Czechoslovakia. East Germany’s puppet leader Erich Honeker resigned in October 1989, having predicted that the wall would stand for another 100 years. He was, as he had been for most of life, wrong.

In the end, the wall came down even more quickly than it went up. After a bungled press conference by an East Berlin Communist Party official on Nov. 9, apparently relaxing the regulations on travel to the West, thousands of jubilant East Germans massed at the wall and demanded that the crossing gates be opened. The more enterprising climbed on top, where they were joined by their brothers and sisters from the other side. Vastly outnumbered and without orders (their commanders were equally confused), the guards simply stood aside. The wall had fallen.

“Twenty-eight years after locking its citizens in one of the largest prisons ever constructed through the Berlin Wall, the East German regime has given in to the irresistible pressure of freedom.”

From an editorial in Arab News on Nov. 11, 1989

The beaming, blond-haired young man at the immigration counter in Berlin’s Tegel Airport was friendly but firm. “No need!” he declared. “No need to stamp the passport! Today we’re one country once more! A historic day!” We all pleaded: “But you don’t understand, that’s precisely why we want our passports stamped.”

Eventually the pfennig dropped. With Teutonic efficiency, desks were set up in one corner of the arrivals lounge, in front of which anyone with a sense of history queued up to have their passports stamped with that day’s date — Oct. 3, 1990, the day Germany was reunified.

In central Berlin, although the wall had been gone for less than a year, the only sign that it had ever been there was a narrow scar slicing through the heart of the city; the only sign, that is, until you crossed from what had been West into what had been East.

A page from the Arab News archive showing the news on Nov. 11, 1989.

The former was vibrant, a riot of color, and the parties seemed to have been going on since the previous November. The latter was grey — the streets were grey, the buildings were grey, even the people were grey, their faces blighted for a dull pallor betraying decades of poor diet.

Since then, the old East Germany has been playing catch-up, at an eye-watering reunification cost of €2 trillion ($2.14 trillion), but with considerable success — best personified by Angela Merkel. Brought up in the East German city of Leipzig from the age of 3 months, and a member of the official communist youth movement at the age of 14, she is now the right-wing chancellor of Germany. Reagan would be proud.

- Ross Anderson, associate editor at Arab News, was on duty as a senior editor at Today newspaper in London the night the Berlin Wall came down. He visited Germany the following year, and was in Berlin on reunification day, Oct. 3