ACCRA, Ghana: Despite the loss of its strongholds in Iraq and Syria at the hands of a US-led international coalition, the terror group Daesh has been making alarming advances across the African continent, particularly in notoriously unstable regions such as the Sahel, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and Mozambique.

The resurgence of Daesh in Africa is not only a cause for grave concern for the continent, but it also poses a potential threat to global security, especially with the pace of foreign fighter mobilization in fragile states and the transnational appeal of Islamic radicalism.

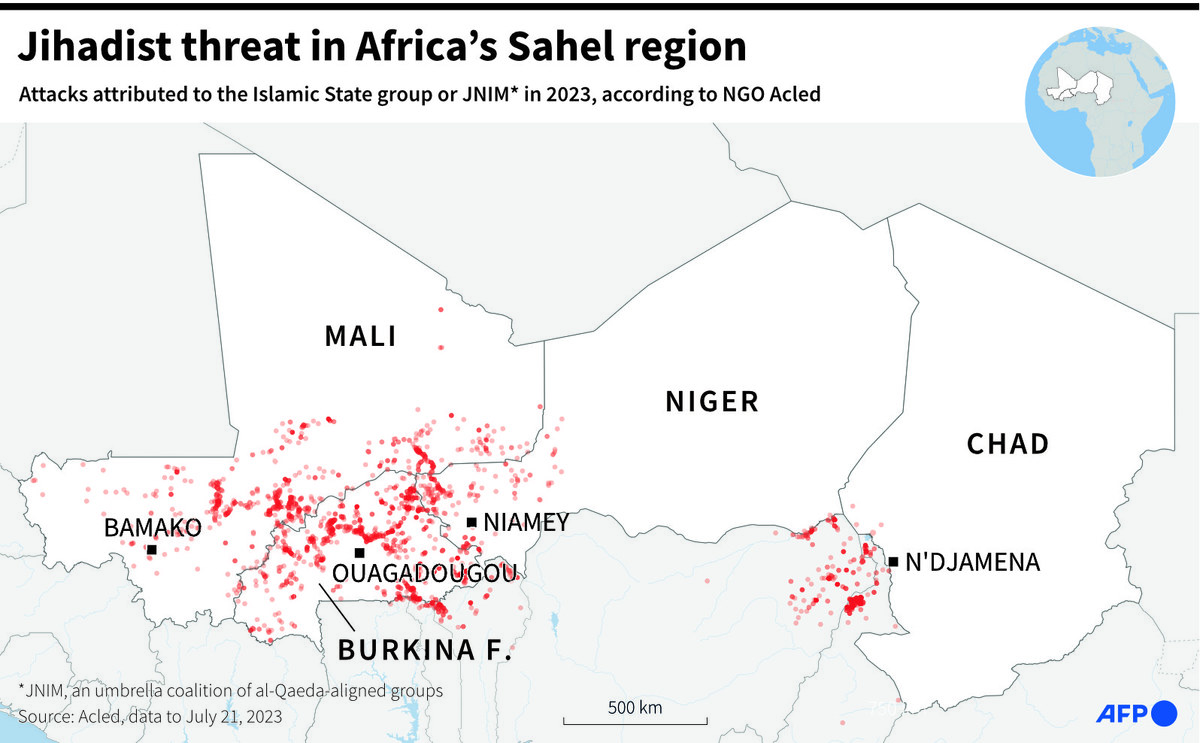

Map locating jihadist attacks attributed to the Daesh or other jihadist groups since 2021 to July 21, 2023 in the Sahel region. (AFP/File)

Recent developments, including arrests in Spain linked to recruitment efforts for Mali, underscore the growing interest and activity of Daesh in Africa. Meanwhile, the substantial revenues generated by Al-Shabab, which takes in an estimated $120 million from extortion alone, is cementing its position as the most cash-rich extremist group in the continent.

As international involvement wanes in the Sahel and regional governments grapple with internal instability, terrorist organizations are exploiting the resulting vacuum to escalate their activities.

Islamist fighters loyal to Somalia’s Al-Qaida inspired al-Shabab group perform military drills at a village in Lower Shabelle region, outside Mogadishu. (AFP/File)

Climate risks, food insecurity and metastasizing violence were all set to intensify in the West African Sahel, predicted a World Economic Forum report of January 2019.

Since then, the withdrawal of French and European forces from Mali, coupled with the suspension of UN peacekeeping missions, has emboldened militant groups, leading to a spike in attacks on civilian populations and security forces.

French anti-jihadist troops began pulling out of Mali in 2022 amid a disagreement between France and West African's nation's military rulers. (Etat Major des Armees nadout via AFP)

In Mali, where a fragile transition to civilian rule is underway amid escalating violence, Islamist groups such as Jama’at Nusrat Al-Islam wal-Muslimin and the Islamic State Sahel Province have intensified their offensives, aiming to consolidate control over northern territories.

The withdrawal of UN peacekeepers has left a security void that these groups are keen to fill, leading to increased clashes with both government forces and Tuareg rebel factions.

Neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso and Niger are also grappling with lawlessness and soaring violence. Recent attacks by extremist groups have resulted in large casualties among security personnel and civilian populations, worsening the already precarious security situation in these countries.

Fighters of the Azawad National Liberation Movement (MLNA) gather in an undisclosed location in Mali. Fearful of being caught in the middle of the conflict engulfing Mali, the country's Tuaregs helped in the French-led campaign to drive Islamic radicals out of the country. Now they have to fight on their own. (MNLA handout photo/AFP)

The massacre at a public event in the Russian capital, Moscow, last month, which killed at least 140 people, was one of the largest terrorist attacks in recent years, particularly after the thwarting of plots in locations like Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, France and Turkiye, along with dozens of recent terrorism-related arrests.

European governments have moved to their highest alert levels for many years.

INNUMBERS

• 5,000 Estimated Daesh fighters in Iraq.

• 50% Africa’s share of terrorist acts worldwide.

• 25 Central Sahel region share of terrorist attacks worldwide.

• $25 million Estimated financial reserves of Daesh.

The entity accredited with many of these audacious plots is Daesh’s “Khorasan” branch, or Daesh-K, which is based in Afghanistan and is active throughout Central and South Asia.

Amid these developments, the lack of international support poses a clear and imminent danger to the stability of the entire Sahel region, a difficult-to-monitor territory spanning several countries from the Atlantic coast to the Red Sea.

Furthermore, last year’s coup in Niger — one of the poorest countries in the world with minimal government services — and the subsequent suspension of the country from the African Union have further complicated efforts to address the terrorist threat. With regional alliances shifting and international assistance dwindling, the prospects for effectively countering terrorism in the Sahel appear increasingly uncertain.

In addition, extremist groups have demonstrated their capability to launch attacks beyond the Sahel, posing a direct threat to the security of coastal states of West Africa, including Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Ivorian soldiers carry the coffins of four compatriots serving with United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali at a military base in Abidjan on February 22, 2021. The four were killed during an attack by extremists. (AFP)

“To understand their recent re-emergence, it’s important to look back at the group’s beginnings, how they engaged with other violent extremist organizations and non-state armed groups in their sub-region,” Aneliese Bernard, director at Strategic Stabilization Advisors, an advisory group focused on conflict and insecurity, told Arab News.

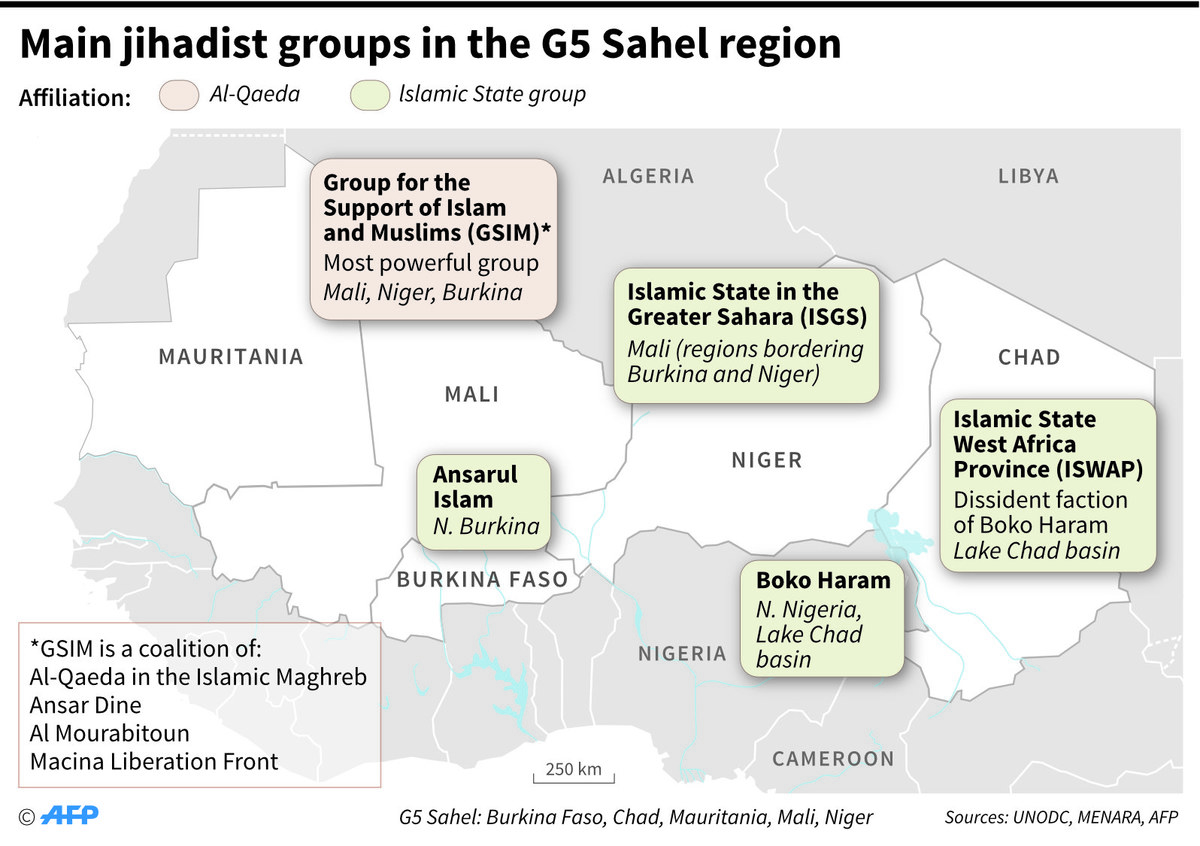

She pointed out that ISSP initially partnered with Al-Qaeda-aligned groups until 2019, when their alliance broke due to differences in governance methods. JNIM’s focus on redistributing revenue clashed with ISSP’s individual looting approach, leading to defections and tension between the groups.

“There were other reasons as well, including the fact that the regional security forces were very focused on reducing IS Sahel’s footprint in Niger, pushing them into space that was controlled by JNIM, causing the groups to compete over space and clash further,” Bernard said.

Other internal factors also contribute to the rise of Daesh in Africa. The leader of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, the predecessor to ISSP, was killed by French forces in the Sahel in August 2021, and “the group was quiet for a bit as leadership and its structure recalibrated.”

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Some suggest that ISSP and JNIM might have called a truce, although clashes continue intermittently. Others stress that the security vacuum in Niger created by the July 2023 coup has likely emboldened ISSP to resume its activities.

Also, “the disintegration of key regional alliances, such as the G5 Sahel, following the withdrawal of key members (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso), has exacerbated the problem,” Souley Amalkher, a Nigerien security expert, told Arab News.

Previously, the G5 Sahel consisted of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, and focused on development and security issues in West Africa. By the end of 2023, only Chad and Mauritania remained, announcing that the alliance would soon dissolve.

“Without effective governance structures in place, addressing terrorism becomes increasingly challenging, underscoring the urgent need for improved governance policies and the creation of secure environments for local populations.

“To address these challenges, there is a pressing need for regional collaboration between Sahelian states and those in North Africa, particularly Libya and Algeria. Strengthening regional initiatives can help fill existing gaps in counterterrorism efforts and bolster the resilience of affected regions,” Amalkher said.

The root causes of Daesh’s expansion in Africa are manifold. Prominent among them are the fragility of local state structures, social injustice, ethnic and religious conflict, and economic inequality.

Insufficient rainfall since late 2020 has come as a fatal blow to populations already suffering from a locust invasion between 2019 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic in Baidoa, Somalia. The situation in the Horn of Africa has raised fears of a tragedy similar to that of 2011, the last famine that killed 260,000 people in Somalia. (AFP/File)

“Daesh and other extremist organizations in Africa are predatory groups that rely on exploiting absences in governance and security,” Bernard said.

“They operate as insurgents rather than traditional terrorists, often launching guerrilla-style attacks before dispersing into local communities. Then, heavy-handed security responses contribute to grievances and fuel extremist recruitment.”

Bernard explained that counterterrorism efforts can often backfire, furthering even more fighting and bloodshed. “These efforts, if lacking coordination with security operations, often fall short against insurgents who adapt quickly, emphasizing the need for more effective strategies addressing root causes,” she said.

In the DRC, the Daesh-affiliated Allied Democratic Forces are just one of over 100 militias and active armed groups. Despite joint efforts by Uganda and the DRC to combat the ADF in 2021, the group remains elusive and difficult to eradicate.

An aerial image shows displaced people fleeing the scene of an attack allegedly perpetrated by the rebel group Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) in the Halungupa village near Beni in DR Congo on February 18, 2020. (AFP/File)

Recently, Uganda raised its security alert as ADF militants crossed into the country, underscoring the persistent nature of the threat posed by the group. In Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, the threat of terrorism continues to pose a significant challenge. Despite initial momentum against ISIS-Mozambique, inadequate coordination and tactics have hindered efforts to eliminate the group.

IS-M’s use of guerrilla warfare tactics and constant movement make it difficult for security forces to root them out, “with some operations seemingly stuck in a routine of patrols and defense rather than actively pursuing the group,” Canadian security expert Royce de Melo told Arab News.

The presence of other armed groups, including the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group, which recently rebranded itself as the Africa Corps, complicates the security landscape within and beyond the Sahel. De Melo said: “Their involvement has fueled anti-government sentiments and served as a rallying cry for Islamist groups, portraying the Russians as oppressors.”

He added that Wagner’s involvement in Mozambique to combat IS-M in Cabo Delgado ended in failure “due to incompetence, racism and internal conflicts.”

Protesters holds a banner reading "Thank you Wagner", the name of the Russian private security firm present in Mali, during a demonstration organized by the pan-Africanst platform Yerewolo to celebrate France's announcement to withdraw French troops from Mali, in Bamako, on Feb. 19, 2022. (AFP)

The rise of extremist violence in Africa is not only a security concern; it also compounds the region’s pervasive humanitarian crisis. Displacement, food insecurity, and economic instability are further worsened by the activities of terrorist organizations, creating a vicious cycle of instability and suffering for millions of people across the continent.

“When evaluating the success of counterterrorism strategies, if terrorist groups remain active, continue to launch attacks, and even grow in strength despite efforts to eradicate them, it becomes evident that current strategies are ineffective and require reassessment,” De Melo said.

“Training, discipline, equipment, technology and culture, as well as good governance, good leadership and morale, are all factors in having a powerful and effective security force that can take the war to Daesh.”