RIYADH/DUBAI/NEW DELHI: Arab countries are braced for a sharp rise in the price of all things sweet after it emerged this week that India, a major supplier of agricultural products to import-reliant Middle East, plans to suspend sugar exports from this October until September next year.

According to three Indian government sources who spoke to Reuters news agency, New Delhi imposed the 11-month ban — the first of its kind in seven years — mainly due to reduced cane yields caused by a lack of rain over the summer monsoon season.

A tractor operator prepares a sugarcane field for planting in Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, India. Lack of rainfall in some parts of the country has prompted the government to suspend exportation of sugar. (Shutterstock)

“This potential ban stems from inadequate rainfall in critical sugarcane cultivating districts,” Pushan Sharma, director of research at CRISIL Market Intelligence and Analytics, told Arab News.

Although rainfall distribution in the sugarcane-growing states of Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka was normal this summer, Sharma says “a few key districts have received lesser rainfall, and the yields are expected to be lower” in the 2023-24 sugar season.

The fall in production is a major concern for the sugar industry as these states alone account for more than half of India’s total sugar output.

Reduced production in India and the country’s absence from the world market will undoubtedly cause price increases at a time when sugar was already trading at multi-year highs.

There are now renewed fears of further inflation in global food markets, particularly in the Arab world, which buys much of its sugar from India.

“There are some Arab countries that will not be able to absorb the price increase shock, and this will affect its imports, its stock, and the distribution process,” Fadel El-Zubi, a lead consultant for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in Jordan, told Arab News.

“These Arab countries will witness further inflation, at a time when their local currencies are already weak.” Therefore, these countries need to take proactive measures ahead of anticipated disruptions in the food market, he said.

The prices of sweets and other sugary food products could rise in the Arab world, which buys much of its sugar from India. (Shutterstock)

Arab countries will not weather future price fluctuations “unless they start implementing the right food system and gradually increase self-sufficiency.”

While these countries do not necessarily need to achieve total self-sufficiency, El-Zubi added, they do need to increase the current level of production and depend less on importing food items.

El-Zubi predicts “some consumption behavior” will change as a result of the sugar export suspension, but such a change “can’t happen overnight.”

FASTFACTS

India to suspend sugar exports from October 2023 to September 2024.

Middle East countries are major importers of Indian sugar.

Move is expected to increase food inflation in the Arab world.

The rise in crude oil prices in recent years, which invariably impacted the cost of freight, had made India a popular choice for Middle Eastern sugar importers, given its relative proximity compared to other major sugar producers like far-flung Brazil.

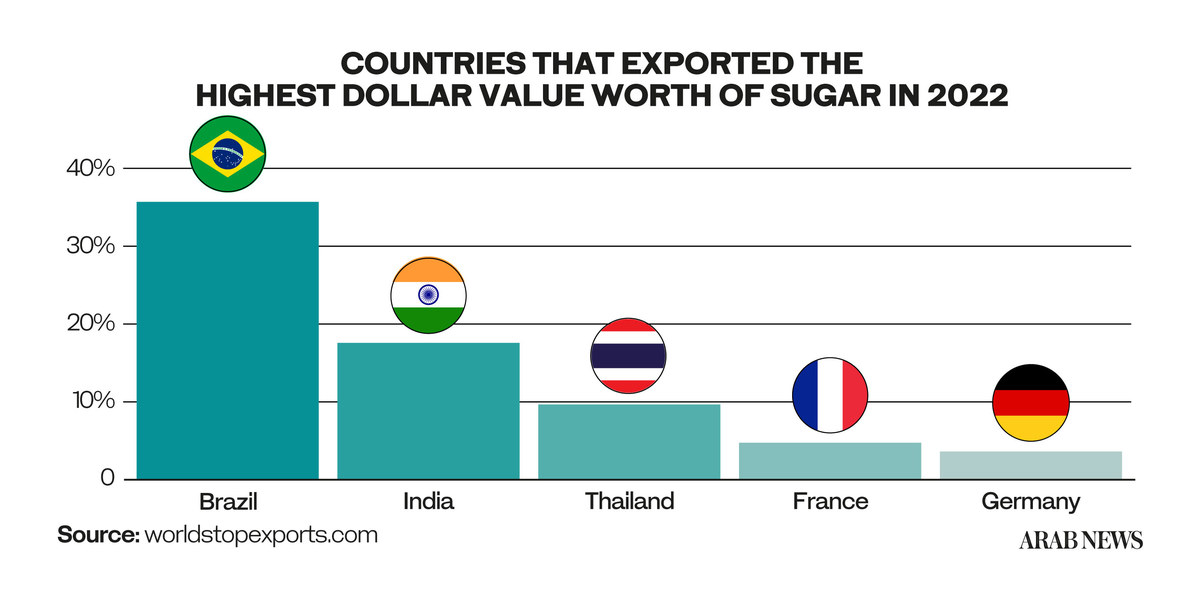

Nevertheless, Arab countries, mainly in North Africa, imported approximately 10 percent of Brazil’s sugar exports in the first quarter of 2023.

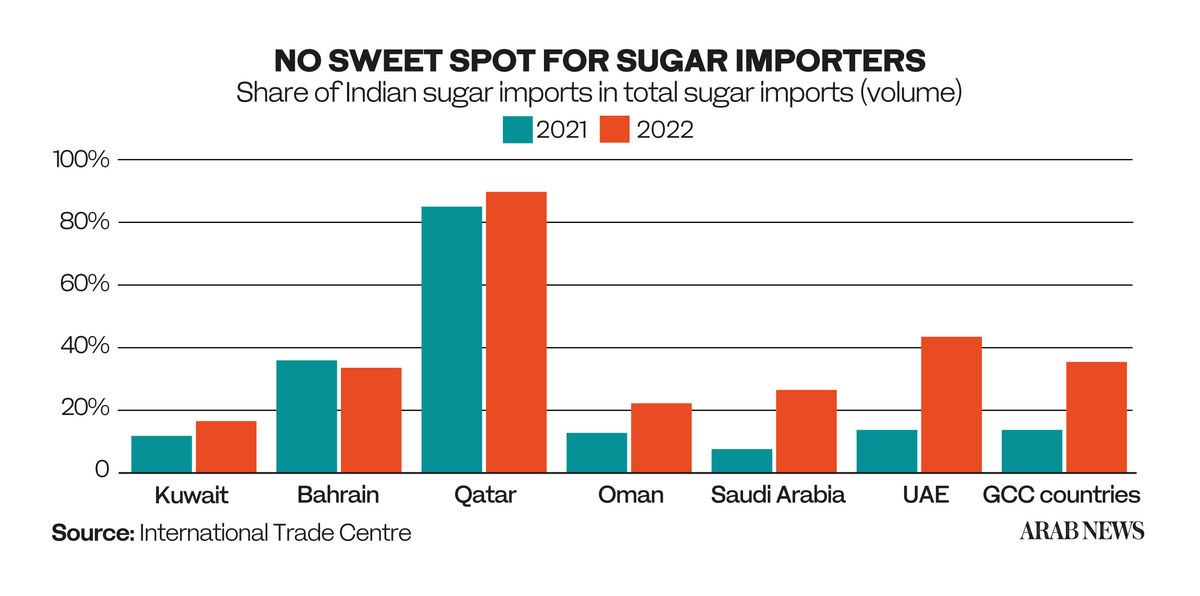

Last year, Qatar imported 90 percent of its sugar from India, the UAE 43 percent, Bahrain 34 percent, and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait 28 percent each, according to figures from the International Trade Center.

Sugar is a staple ingredient in Gulf Cooperation Council countries, making them especially susceptible to price rises as a result of the export suspension.

“Since all GCC countries have significant dependency on Indian sugar, an export ban in India would lead to lower supplies in the global market, making imports more expensive for all sugar-importing countries,” said Sharma.

An Egyptian man shows a bag of sugar he just bought from a truck in the capital Cairo on October 26, 2016, as the country suffered from a sugar shortage. With India's move to suspend the exportation of sugar, some countries in the Middle East are expected to be hit badly with inflated sugar prices. (AFP/File)

And these countries will not find it easy to find new or substitute sources for their sugar in the meantime.

“While these sets of restrictions will force the Arab world to diversify their supply sources, it will take time to change suppliers,” Anupam Manur, an assistant professor at the Bangalore-based Takshashila Institution, told Arab News.

“In the short-run, higher food inflation will be seen.”

Coffee lovers in the Middle East may have to do with less sugar to cushion themselves from the impact of Inda's sugar export ban. (AFP)

Despite these predictable ramifications, the Indian government has concluded the ban was a necessary step.

“Domestic considerations come into play in the ban. The government is looking at the domestic consumers’ interest,” Gokul Patnaik, chairman of Global AgriSystem Pvt. Ltd. and former director of the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, told Arab News.

“Farmers and growers can make some money through increased prices. In the case of onions, the growers are affected directly. In the case of sugar (a processed product), it’s an indirect effect. But it harms the growers in all cases.”

For Manur, a pattern is emerging in India’s agricultural trade policy. New Delhi’s “successive restrictions on export” clearly indicate it seeks to “prioritize domestic supply requirements” over export earnings, he said.

Workers harvesting sugarcane in Maharashtra, India. (Shutterstock photo)

Overall retail inflation in India was also a recent concern, with the consumer price index jumping to a 15-month high of 7.44 percent in July and food inflation to 11.5 percent, its highest in over three years.

“However, inflation is as much a result of demand-supply mismatches as it is with consumer expectations,” said Manur.

“Ironically, by undertaking this series of restrictions on exports, it is sending a signal of scarcity, and that can drive up prices by itself. It also diminishes incentives at the margin for increased production.”

India has proven to be one of the fastest-growing sugar exporters in recent years. Last year, it was the second-largest exporter of the commodity worldwide, selling $5.7 billion worth, up from a comparatively paltry $810.9 million in 2017.

New Delhi’s increased sugar exports can be attributed to a number of factors ranging from favorable weather conditions to rising domestic sugar production and government policies supporting sugar exports.

Indian workers loading sugarcane at the Triveni sugar refining factory in Sabitgarh village, in Bulandshahr district of Uttar Pradesh state. (AFP/File)

“India holds the position of the second-largest sugar exporter globally after Brazil, contributing to 15 percent of global exports,” said Sharma.

“However, for the October 2022 to September 2023 sugar season, the export share is expected to decline to 11 percent due to a significant drop in exports.”

Sugar is not the only Indian food export that has proven unreliable in recent months.

The country surprised foreign consumers last month by imposing a ban on non-basmati white rice exports. It also set a 40 percent duty on onion exports in an attempt to stabilize food prices ahead of state elections later this year.

Indian workers pack processed sugar at the Triveni sugar refining factory in Sabitgarh village, in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh. New Delhi's decision to suspend the exportation of rice, sugar and other staples could backfire, with India eventually losing its share of the market in the Middle East, critics warn. (AFP/File)

“This kind of knee-jerk reaction of banning the export is not good for our well-being as a long-term exporter,” said Patnaik. “At best, there can be adjustments in export taxes, but the total ban should not be done.

“If you ban, you lose credibility as a long-term supplier. The ban will no doubt affect the Arab world. But it will also affect India’s credibility.”

Manur concurred with this assessment. “India might experience strained trading relations with its trading partners and could result in either retaliatory tariffs or the loss of negotiating power in future trade talks,” he said.

“Further, this can hurt India in the long run as many countries would scramble to diversify their food suppliers.”

In the short term, it could negatively impact poorer countries in the Arab world, where food security is already a concern, especially since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war, which threatens to imperil grain exports to major importers.

While major sugar-importing countries like the UAE have sufficient financial cushioning to deal with increased food prices, developing nations in the region do not.