JEDDAH: Despite the record-fast rescue by Lebanese security services on Tuesday of a kidnapped Saudi citizen, the incident comes as yet another reminder of the many heists, abductions and hijackings that have plagued the Arab country since the 1970s.

Mashari Al-Mutairi, an employee of Saudi Arabia’s Saudia airlines who lived in the Beirut suburb of Aramoun, was abducted at about 3 a.m. on Sunday. The Lebanese Army’s intelligence directorate found and freed him after a security operation on the border with Syria.

He was received at the Saudi Embassy in Beirut by Ambassador Walid Bukhari, who said in a statement: “The released Saudi citizen is in good health, and we thank the army and internal security forces. The security efforts confirm the Lebanese authorities’ keenness to secure tourism security.”

News of Al-Mutairi’s abduction will have come as little surprise to millions of Lebanese who have endured decades of similar disappearances, hostage situations and armed robberies — crimes that are again on the rise as the nation grapples with chronic economic woes.

Saudi Ambassador to Lebanon Walid bin Abdullah Bukhari, right, and Lebanon’s caretaker Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi attend a press conference at Saudi Arabia’s embassy in Beirut, Lebanon. (Reuters)

In the first 10 months of 2021, the number of car thefts rose by 212 percent, robberies by 266 percent and murders by 101 percent compared to the same period of 2019, according to figures from International Information, an independent consultancy based in Beirut.

Ever since the 1975-90 civil war, Lebanon has been a transit, source and destination country for arms trafficking. These same networks are today used to move stolen goods, control the black market and facilitate the burgeoning drugs trade — many of them controlled by the armed Shiite group Hezbollah, which continues to dominate Lebanese public life.

“Any country that has a non-state actor within it is considered a ‘failed state,’” Salman Al-Ansari, a Saudi political researcher, told Arab News. “Lebanon has never been this dominated by a militia that works for an outside power.

“The crime, drug smuggling, economic collapse, currency decline are only symptoms of the actual root problem, which is the lack of national sovereignty. There is no point in rectifying the symptoms as long as the actual root problem exists. It’s like hoping to treat a serious illness with a painkiller.

“Lebanon should change course and realize that their future is very dark if they allow a non-state actor to dictate its trajectory.”

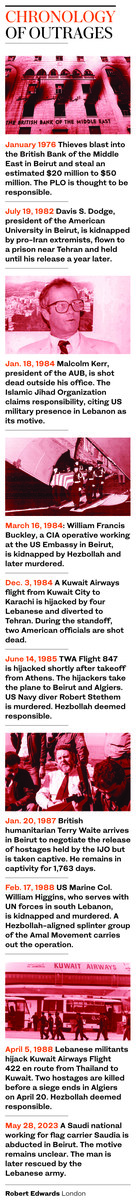

Events in Lebanon today have echoes of the bad old days of the 1980s, when kidnappings, torture, murder and drug trafficking reached endemic proportions against the backdrop of the civil war, which devastated the country.

Events in Lebanon today have echoes of the bad old days of the 1980s, when kidnappings, torture, murder and drug trafficking reached endemic proportions against the backdrop of the civil war, which devastated the country.

Back then, Westerners were common targets. In 1982, pro-Iran extremists kidnapped Davis S. Dodge, then president of American University in Beirut, from the university campus. He was flown to a prison near Tehran and held until his release a year later.

In 1984, Dodge’s successor as president of the AUB, Dr. Malcolm Kerr, was shot dead by two gunmen outside his office. The Islamic Jihad Organization claimed responsibility for the killing, citing the US military presence in Lebanon as its motive.

The same year, William Francis Buckley, a CIA operative working at the US Embassy in Beirut, was kidnapped by Hezbollah and later murdered. One of the reasons for his abduction was thought to be the upcoming trial of 17 Iran-backed militants in Kuwait.

Several times during this period, whole planeloads of people were taken hostage. In 1984, a Kuwait Airways flight from Kuwait City to Karachi, Pakistan, was hijacked by four Lebanese and diverted to Tehran.

Due to unmet demands, the hijackers shot and killed American passengers Charles Hegna and William Stanford, both of whom were officials from the US Agency for International Development, before dumping their bodies on the tarmac.

Less than a year later, on June 14, 1985, TWA Flight 847 was hijacked soon after taking off from Athens. For three days, the plane went to and from Algiers and Beirut. US Navy diver Robert Stethem was murdered aboard the flight.

Dozens of passengers were held hostage over the next two weeks until they were finally released by their captors after some of their demands were met. The hijackers had demanded the release of 700 Shiite Muslims from Israeli custody.

Western analysts accused Hezbollah of hijacking the plane, a claim the group rejected.

In 1987, British humanitarian and hostage negotiator Terry Waite traveled to Beirut to negotiate with the IJO, which had taken several hostages. However, he was himself abducted by the group and remained in captivity for 1,763 days — the first four years of which he spent in solitary confinement.

A year later, Col. William Higgins, a US marine serving with the UN forces in South Lebanon, was kidnapped and murdered by a Hezbollah-aligned splinter group of the Al-Amal movement, “Believers Resistance.”

Malcolm Kerr, President of the American University of Beirut, who was shot and killed by gunmen as he arrived at his office on campus. (AUB)

Although Lebanon is no longer in the grip of outright civil war, the financial crisis which began in 2019, combined with the political class’s failure to establish a new government, have created an environment of growing lawlessness and desperation.

Indeed, there are indications that the kidnapping of Al-Mutairi could have been orchestrated by a criminal organization with a hand in the production and trade of the amphetamine Captagon, which blights the entire region.

Lebanese news station MTV reported in recent days that a drug dealer known as Abu Salle, who is described as one of the region’s most prominent cartel bosses, was behind Al-Mutairi’s kidnapping.

The Lebanese Army raid of a Captagon factory in connection with the kidnapping lends weight to this theory.

Criminal networks move stolen goods, control the black market and facilitate the burgeoning drugs trade in Lebanon — many of them controlled by Hezbollah. (AFP)

Although Lebanese officials were quick to condemn the kidnapping, there are concerns the incident could hamper efforts to normalize relations between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, which have long been strained by the influence of Hezbollah.

However, Al-Ansari is confident the kidnapping will not obstruct progress on normalization.

“This could be considered a small obstacle in the way, but at the end of the day, Saudi Arabia is committed to having Lebanon back to the Arab fold in a way that it can have its own sovereignty away from Iranian hegemony,” he said.

In March, Saudi Arabia and Iran restored diplomatic relations under a Chinese-mediated deal. How this new arrangement will impact the activities of Iran’s proxy forces throughout the region, however, remains ill-defined.

TWA Boeing 727 captain John L. Testrake from Richmond, Missouri, emerges from the cockpit of his hijacked airliner 19 June 1985 at Beirut airport to talk to newsmen. (Getty Images/AFP)

“It is still unclear what the Chinese mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran will result in with regard to the Lebanese file,” Al-Ansari said. “It will de-escalate the tension, but it will not solve the problem overnight.”

Although Lebanon is a long way from reaching stability, Al-Ansari believes Saudi Arabia “will work hard with the highest level of government in Lebanon to find a way to have political and economic reforms, combat corruption and drug smuggling, and have the right kind of governance.”

International observers warned of a potential power vacuum after long-time president Michel Aoun left power in October. To this day, Lebanon’s parliament has yet to elect a new president, prolonging the nation’s political paralysis.

“The Saudi ambassador to Beirut has been vocal and supportive in finding a solution to the power vacuum and pushing for reforms and appointing a government, because at the end of the day, Saudi Arabia can’t provide anything if there is no actual solidified government in Beirut,” Al-Ansari said.

“Saudi Arabia doesn’t want anything from Lebanon except for it to be politically stable and prosperous. It will take a long time to accomplish these goals, but at the end of the day, it’s up to the Lebanese to decide their future, and the Saudis will be helping them with whatever they can.”