RIYADH: Muslims have paid great attention to miniatures and manuscripts throughout history.

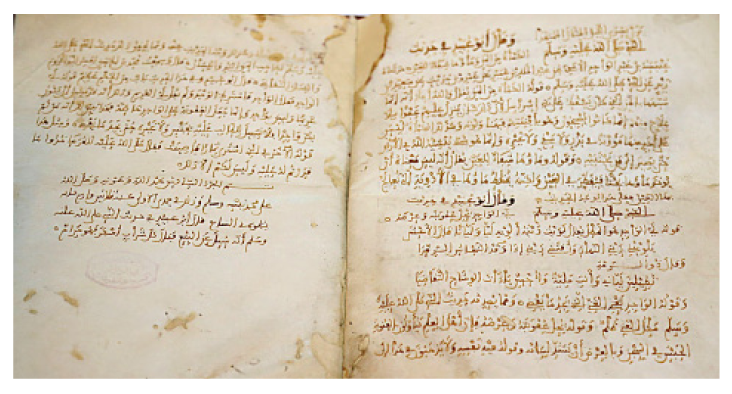

In Arabic the word miniature translates to munamnamat, a small painting on paper, and it was a way to preserve what Arab and Islamic artists had created.

They became valuable artifacts and told stories of the religion’s golden age, leaving a tradition that has been studied by researchers to understand Arab and, in particular, Islamic culture and its evolution.

These small yet intricate scrolls reveal stories that have been captured with an extreme focus, offering a detailed look into the lives of people through the ages.

The earliest examples date from around 1000 AD. Scholars divide Islamic miniatures into four types: Arabic, Indian, Ottoman, and Persian.

The King Abdulaziz Public Library has, since its establishment in 1988, contributed to the preservation of miniatures and manuscripts to protect Arab and Islamic heritage and make it available to researchers.

Dr. Bandar Al-Mubarak, who is the library’s director general, said there were around 8,000 original manuscripts in the collection and that they had been digitally converted.

The library has bought most of the miniatures and manuscripts it owns, they have not been donated, and it has certain criteria when acquiring a manuscript. Rare, old, containing exquisite artwork and possessing a distinctiveness that sets it apart.

“The library takes great care of the manuscripts it owns,” Al-Mubarak told Arab News. “We have some of the rarest in the world. The oldest manuscript is “Al-Nawader fe Al-Lugha” (Stories of Language), which dates back to the year 377 Hijri (987 CE). Our manuscripts cover a variety of subjects, including medicine, Qur’ans and languages, and important topics in Arab and Islamic history such as horsemanship and more.”

The miniatures, manuscripts, and old books are sterilized annually to prevent their deterioration. They are kept in a special room that is cold and dark to thwart insects and bacteria because both of these can damage the paper and even the animal skin used in some manuscripts.

The library also has a particular way of storing the precious books, especially the delicate ones, by laying them down horizontally on shelves instead of storing them vertically, similar to the way that libraries in the early Islamic era used to store them. They are positioned that way to protect the spine of the book from damage. The spine is the most important feature of a book's structure and is one of its most delicate features, so great care must be taken to avoid damaging it.

Islamic miniatures have captured images of everything from customs, rituals, behavior and historical events to architecture, costumes, and the arts, helping researchers to learn about Islamic aesthetics and morals.

The distinctiveness of the manuscripts and miniatures lie in their detail. From double rule borders in red, gold, brown or green to page orders in gilt floral patterns or geometric shapes.

“The library recently launched a new manuscript-preservation project,” said Al-Mubarak. “It has always worked to preserve manuscripts but the new project includes enhanced preservation methods, including professional conservation treatments, to prolong their lifespan and allow more people to benefit from them,”

The library owns one of the famous manuscripts copied in 1772 AD by Abdelkader Bin Salim Al-Shafei called “Dalail Al-Khayrat Wa Shawariq Al-Anwar Fi Dhikr Al-Salat Ala Al-Nabi Al-Mukhtar,” (Guidebook of Benefits and Illuminations of Prayers to the Chosen Prophet).

This manuscript is one of the most famous books mentioning prayers for Prophet Muhammad. The author collected the forms of prayer and divided them into seven sections to read throughout the week.

This book has grabbed the attention of many Sufi scholars, who have made it part of their daily routine.

What makes the manuscript even more special are the two illustrations of the Kaaba in Makkah, at the back of page 30, and the other of the holy mosque in Madinah, and the tombs of the Prophet Muhammad and his two followers Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq and Omar bin Al-Khattab on page 31.

The library has also shown interest in acquiring Islamic scientific heritage. One of the miniatures that the library preserved is a copy of “Anatomy of the Human Body” by one of the 15th century’s most prominent medicine scholars, Mansour bin Mohammed bin Ahmed bin Yusuf bin Ilias Al-Kashmiri.

Al-Kashmiri preceded the scientist Andreas Vesalius, who published a classic work on anatomy, as well as Leonardo da Vinci.

European scientists have benefited from Al-Kashmiri’s drawings of the human body and anatomy that became part of their medical education and have helped in a number of medical discoveries.

Iraq, Iran, and Syria have been among the most active countries in providing miniature arts and paid attention to it because of their past heritage in drawings and sculpture.

One of the more well-known Persian miniatures that the library possesses is “Khamsat Nizami,” a selection of five poetic works from Nizami Ganjavi. The five selections are: “Makhzan Al-Asrar,” “Khosrow and Shirin,” “Layla and Majnun,” “Haft Peykar,” and “Eskandar-Namah.”

The inscriptions at the beginning of each of the book's five sections, as well as the clear and beautiful calligraphy, are what make this item so special.

The book itself is a mixture of tragic romance, fictional versions of real love stories, and popular Persian tales.

Even though miniatures were not popular in the history of the Arabian Peninsula’s culture, the library restores them in order to preserve the past and provide researchers with the opportunity to study them.