DUBAI: The largest Jewish population that ever existed in the Arab world was in Morocco, which was home to over 250,000 Jews by the 1940s. A free photography exhibition, which runs at the Museum of the Art and History of Judaism (mahJ) in Paris until May next year, offers a rare insight into their lives there.

“Juifs du Maroc” showcases around 60 black-and-white photographs and drawings by the late French photographer and painter Jean Besancenot, who travelled to Morocco several times and became enamored with the culture there.

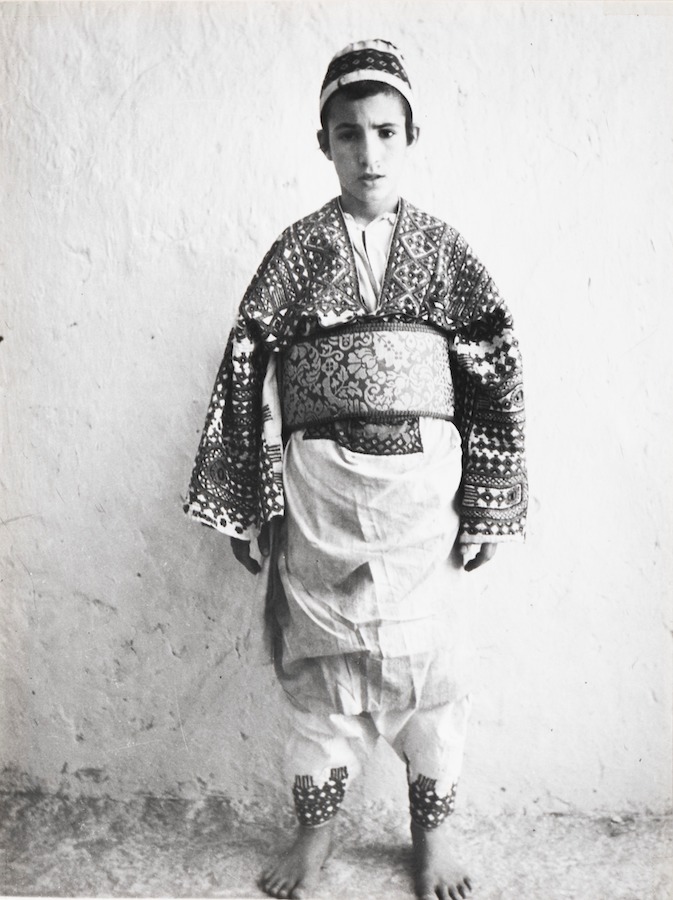

The images on display were photographed between 1934 and 1937. They are both intimate and a documentary-like portrayal of Morocco’s Jewish community — some of men, women and children posing in elaborate attire against a neutral background, others of people practicing daily activities of baking, brewing, and reading. Overall, the exhibition preserves and presents “a priceless record of rural Jewish communities in Morocco no longer in existence,” according to a statement published by the museum.

Erfoud, Tafilalet Region Rouhama and Sarah Abehassera in Wedding Suits mahJ. (Adagp, Paris, 2020)

One of the driving forces behind “Juifs du Maroc” is co-curator Hannah Assouline, a French photographer with more than 30 years of experience, who was born in Algeria and resides in Paris. The exhibition is a particularly personal endeavor for Assouline, since one of the photographs on display is of her father, a then-adolescent Rabbi Messaoud Assouline, who came from a destitute family. The story of how she found this valuable photograph is one of coming full circle and an unlikely coincidence.

“I met Jean Besancenot in 1985, when my interest in photography began,” Assouline told Arab News with some translation help from her assistant Paul. “As soon as Besancenot saw me, he immediately knew where I was from. He told me, ‘You come from Tafilalet (a region in southern Morocco) and you are a Jew.’

“I wanted to buy pictures from him, but since I didn’t have enough money I couldn’t buy a lot,” she continued, adding that Besancenot had 2,800 photographs portraying the Jewish world of Morocco. “He showed me more than 100 pictures — all of Jewish people, among them were many girls and young women.”

Goulmima, Tafilalet Region Young Woman in White mahJ. (Adagp, Paris, 2020)

By chance, Assouline came across a snapshot from 1935 of a very young married couple, and noticed that the boy resembled one of her nephews. Intrigued, Assouline purchased the photograph — along with six more as gifts for her siblings — and was eager to show it to her family.

“I went to my parents’ home to show them the pictures on a Friday night, which is Shabbat,” she said. “My father was very religious and didn’t want to see the pictures on Shabbat. When he finally agreed to look at the pictures, he said in Arabic: ‘It’s me!’ He had never seen this picture before — it took him 50 years to see it. He went through exile, war, moved to a new country with a new story and, in the end, he found his picture.”

It turned out that Assouline’s then-13-year-old father — timid and barefoot — was only playing the part of a groom and was photographed in Erfoud, one of the centers of Moroccan Jewish life at a time when the North African country was a French protectorate.

Erfoud, Tafilalet Region Messaoud Assouline (Tinghir, 1922 – Jerusalem, 2007), 13 years old, in Wedding Suit

Hannah Assouline Collection. (Adagp, Paris, 2020)

The reason why Besancenot was exploring and documenting these closed-off regions was that he was commissioned by the Foreign Ministry and the then newly built Musée de l’Homme in Paris to carry out ethnographical work — through detailed notes, films, and colorful drawings — of traditional Moroccan clothing. In the publicity for the exhibition, the museum notes of the female costumes and adornments that their “repertoire is sometimes common with that of Muslim women.”

The presence of Jewish women dominates Besancenot’s work. Their imposing headpieces and voluminous layering of necklaces, earrings and bracelets was central to their identity, beauty, and in some cases, social status. “In some of the pictures, you’ll see women wearing torn, old clothes but they’re still wearing all their jewelry,” Assouline noted.

“I love the pictures, because Besancenot was a real human,” she said of the photographer’s compositions. “He took pictures without judgment. The pictures are very sensible and he was very close to the sitters. He came often to Morocco to see the people. It was not a one-time shoot – he came day after day to talk with everyone and then he took the pictures. The exhibition is set between 1934 and 1937, but he always came back to Morocco. All his life, he circled around that country.”