TOKYO: Tokyo-born Fuad Kouichi Honda is widely recognized as one of the world’s top Arabic calligraphers. The native Japanese Muslim, who teaches at Daito Bunka University, has won numerous awards for his work, including at the International Arabic Calligraphy Competition. His most famous pieces use passages from the Qur’an.

Fuad began learning Arabic decades ago. Reading the Qur’an in Arabic inspired him to try his hand at Arabic calligraphy, which he describes as “music without sound.”

“Later, I embraced Islam in order to better feel the essence of this faith and to feel God,” he says. “My works are a Japanese style of expressing Islam and Islamic culture.”

His style is also a reflection of landscapes he encountered on his travels through Arab countries. Honda led mineral surveys in the deserts of Saudi Arabia for three years in the 1980s, and he says the beauty of the sand dunes and the calligraphy he saw there combined to ignite his passion for this artform.

Honda began learning Arabic decades ago. (Supplied)

Despite encouragement from his father, Honda was not especially keen on calligraphy as a boy. In fact, he says, he gave up studying it in favor of sports. But when he became an undergraduate in Foreign Studies at Tokyo University in 1965, Honda decided to take Arabic lessons as he was interested in ancient civilizations in the Middle East, particularly Egypt. And it was a choice he initially came to regret.

“I think (Arabic) is the most difficult language in the world,” he says. “I dropped it after two years. The teacher asked me to read a book in Arabic about the legendary Arabic hero, knight and poet Antarah ibn Shaddad. That was seriously difficult literature for me.”

It was topography that brought Honda back to the Arabic language and to calligraphy. After graduating, he joined a Japanese company that was working with the Saudi government to survey and make maps of the Arabian Peninsula.

He traveled to the Kingdom in 1974 as a translator for the company. Several of the maps the company was using bore Arabic calligraphy, and Honda says he fell in love with the art. He started teaching himself to recreate the work he had seen.

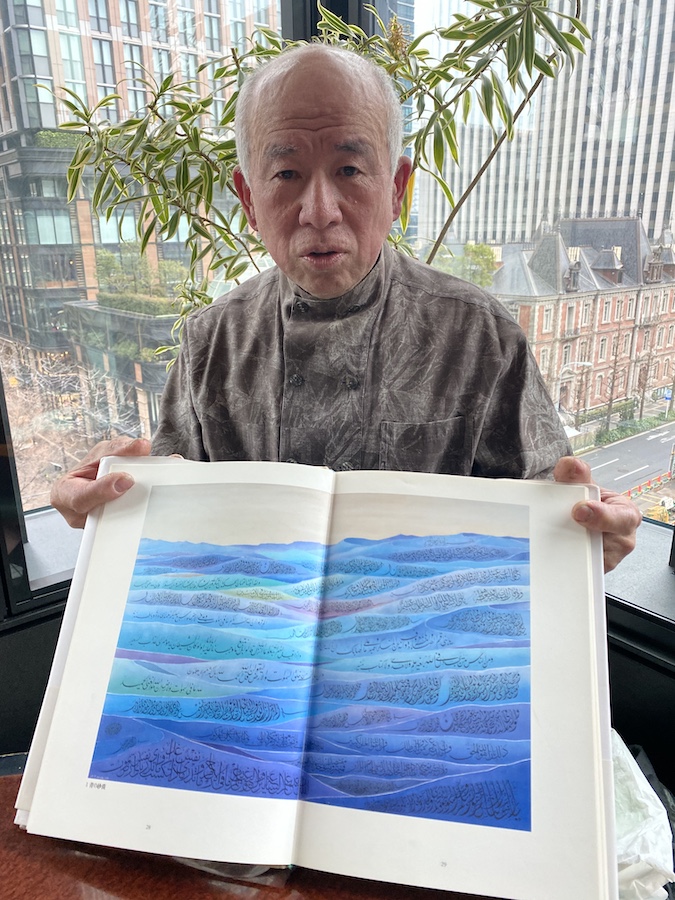

Quran Surat Al-Baqarah148. (Supplied)

Honda recalls that one calligrapher he met, whose job was to write the official correspondence of the petroleum ministry, advised him to buy a beautiful book on Arabic calligraphy by Naji Zein, which became a major influence on Honda's own work.

When he returned to Tokyo, he continued to practice calligraphy and received requests from the Saudi Embassy to create pieces for National Day banners. Other embassies began asking for similar services. And it came to the point where Honda decided he wasn’t content to treat calligraphy simply as a side hobby.

“(When I returned) to Japan in the late Seventies I became an office worker in the company,” he says. “I felt the routine work didn’t fit my life and mind, so I decided to resign and started teaching Arabic.”

He adds that the main motivations for his resignation were a strong desire to “live a free life” and keep learning Arabic calligraphy.

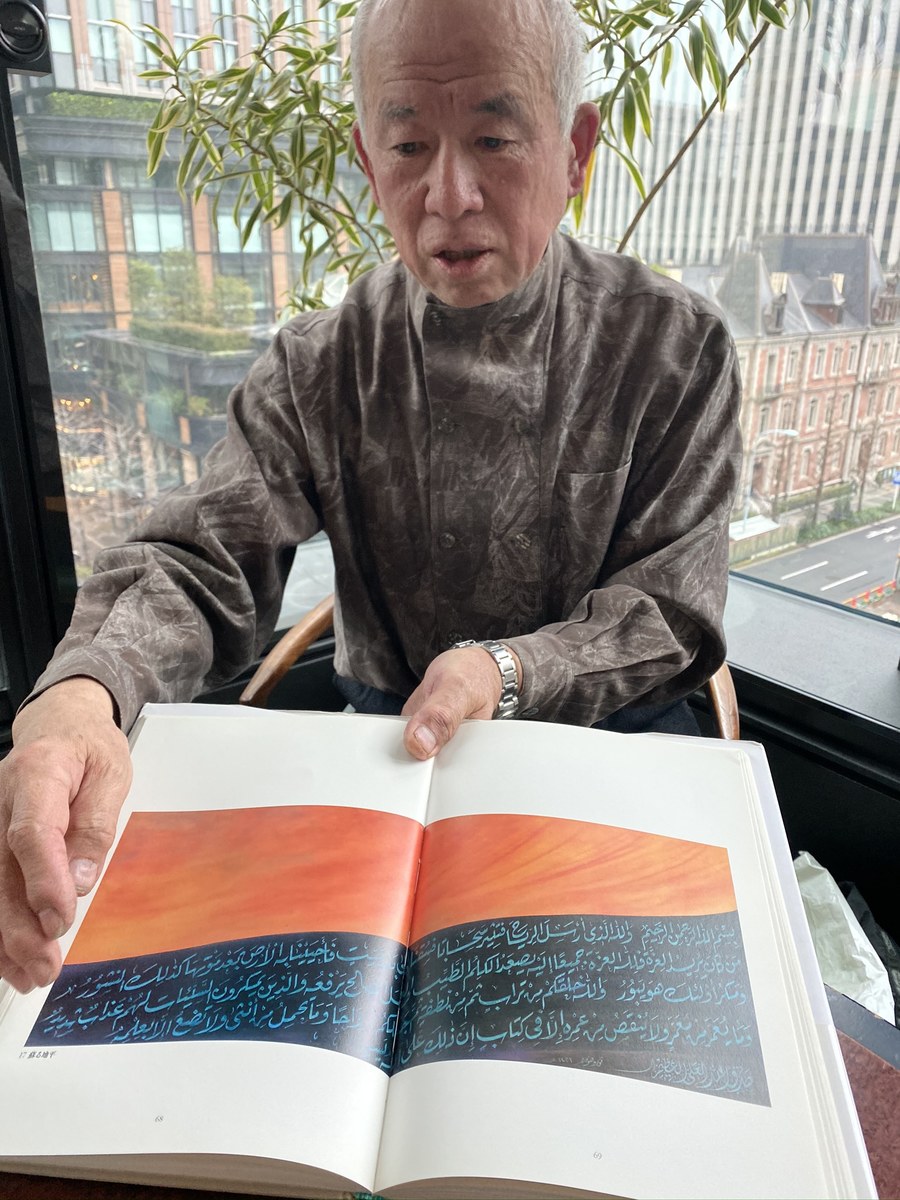

Reading the Qur’an in Arabic inspired Honda to try his hand at Arabic calligraphy. (Supplied)

What Honda did not fully realize at the time was that his way of thinking had undergone a major — albeit subconscious — shift. His time in Saudi Arabia had forged a strong spiritual link for him with the country and culture, but also with Muslims and Islam in general.

He had been interested in Islam since his university days, he says, and that interest deepened as he made Muslim friends in Saudi Arabia, and as he read the Qur’an and other religious books. After returning to his homeland, quitting his job and beginning to explore the language and calligraphy more intensely, Honda decided to convert to Islam.

He declared his conversion at the Islamic Center in Tokyo and adopted the Arabic name Fuad. He says the name, which means “heart,” just came to him. Rather than referring to the organ, he believes it symbolizes his heart’s connection with God.

In 1988, Honda received his first invitation to display his work overseas. He went to Baghdad — taking three of his works with him — to participate in an international Arabic calligraphy conference along with around 180 other calligraphers. It was there that he met the renowned Turkish calligrapher Hasan Chalabi.

Fuad asked the master calligrapher to teach him more about the art, and Chalabi agreed. It was the start of years of correspondence between the two.

He declared his conversion at the Islamic Center in Tokyo and adopted the Arabic name Fuad. (Supplied)

“He corrected me a lot,” says Honda. “I was surprised and disappointed sometimes.” But those corrections decreased over time. And after about a decade of instruction, Chalabi presented Honda with his certificate — with a caveat.

“At the ceremony in Istanbul, he told me the certificate did not mean I had reached my goal, but that it was a new start (and should inspire me to be) more creative and to work harder,” he says. Crucially, the certificate also meant he could now sign his work.

By that time, Honda was creating his own designs and participating in exhibitions. He had received some awards, but says that imitating old works made him feel “limited by tradition.”

“One day, when I was reading verses from the Qur’an, vague formations like circles and triangles flashed in my mind,” he recalls. “I felt this was the inspiration to design new (forms of) calligraphy that reflect the meaning of the Qur’an — so I started doing that.”

While Honda stresses that he has great respect for the heritage of Arabic calligraphy (believing it “sits on top of the fine arts of the world in terms of aesthetic value”), he says he felt a desire to create a style that was more personal to him, with a new background style — an original one with “philosophical meaning” that would bring a new aspect to an ancient art.

He became an undergraduate in Foreign Studies at Tokyo University in 1965. (Supplied)

Colors play a vital role in that style, particularly blue and gold — with blue representing sky, water and eternity, and gold reflecting divinity. “Words about water have a very profound meaning,” he explains. “Water is important in the Qur’an as it has different shapes every moment and this is shown in my design.”

He adds depth to his work through gradual coloring, a technique widely used by Japanese painters. One of his favorite pieces depicts a blue desert with verses from the Qur’an on each sand dune. He was inspired to make it after visiting Saudi Arabia’s Rub’ al Khali, or Empty Quarter and noticing how the dunes changed color depending on time and their shifting shape. He felt the dunes were reminiscent of waves and the delicate lines on their surface evoked the calligraphy of the Qur’an.

Like the art form he adopted, Honda’s career has flourished. In addition to teaching Arabic calligraphy to Japanese students for more than two decades, he has published books, given lectures overseas and established the Japan Arabic Calligraphy Association.

“I believe that all Muslims in the world, regardless of their nationality, (should) take great pride in (Arabic calligraphy), the aesthetic value of which has not been reached by (any other artform),” he says.

“Calligraphers should fully maintain this heritage by adhering to the rules of calligraphy. (But also) introduce further creativity, so that it becomes even more beautiful.”