LONDON: Towering above the fertile Bekaa Valley, the Temple of Jupiter and Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek stand as monumental symbols of Roman power, while the ruins of Tyre echo the splendor of the Phoenician civilization.

Today, these UNESCO World Heritage sites, along with countless other historical landmarks, face a grave threat as the conflict between Israel and Iran-backed Hezbollah fighters encroaches on Lebanon’s unique and ancient heritage.

After nearly a year of cross-border exchanges that began on Oct. 8, 2023, Israel suddenly escalated its campaign of airstrikes against Hezbollah targets across Lebanon.

Smoke rises following an Israeli airstrike that targeted the eastern Lebanese city of Baalbeck on November 3, 2024, amid the ongoing war between Israel and Hezbollah. (AFP)

In recent weeks, Baalbek’s famed Roman temples, celebrated for their architectural sophistication and cultural fusion of East and West, have come dangerously close to being hit.

Although these structures have so far been spared direct strikes, adjacent areas have suffered, including a nearby Ottoman-era building. The city’s ruins, which have survived the test of time and the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war, are now at significant risk.

The ancient city has suffered multiple airstrikes since evacuation orders were issued on Oct. 30 by Israel, which has designated the area a Hezbollah stronghold.

FASTFACTS

• UNESCO World Heritage sites in Baalbek and Tyre are at risk of direct hit or secondary damage under Israeli strikes.

• ALIPH has allocated $100,000 to shelter museum collections and support displaced heritage workers in Lebanon.

• Preserving heritage fosters resilience, identity, and post-conflict recovery, say UNESCO and heritage advocates.

The proximity of these airstrikes has left archaeologists and local authorities fearing that damage, whether intentional or collateral, could be irreversible. Even indirect blasts pose a serious risk, as reverberations shake these ancient stones.

United Nations Special Coordinator for Lebanon Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert (L) and Director of the UNESCO Office in Beirut Costanza Farina (C) visit the Roman citadel of Baalbeck, in the Bekaa valley, on November 21, 2024. (AFP)

“The threats come from direct bombing and indirect bombing,” Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, a Lebanese archaeologist and founder of the non-governmental organization Biladi, told Arab News. “In both ways, cultural heritage is at huge risk.”

Reports indicate that hundreds of other Lebanese cultural and religious sites have been less fortunate. Several Muslim and Christian heritage buildings have been reduced to rubble in southern towns and villages under shelling and air attacks.

“Some of them are known and already registered in the inventory list and some of them unfortunately we know about them when they are destroyed and inhabitants share the photos of them,” said Farchakh Bajjaly.

The six columns of the Temple of Jupiter at the Roman citadel of Baalbeck, in the Lebanese Bekaa valley, on November 21, 2024. (AFP)

Many of these sites carry irreplaceable historical value, representing not only Lebanon’s heritage but also that of the broader Mediterranean and Near Eastern regions.

Baalbek’s origins stretch back to a Phoenician settlement dedicated to Baal, the god of fertility. Later known as Heliopolis under Hellenistic influence, the city reached its zenith under the Roman Empire.

The Temple of Jupiter, once adorned by 54 massive Corinthian columns, and the intricately decorated Temple of Bacchus, have attracted pilgrims and admirers across millennia.

Cultural heritage is a key reason people visit Lebanon. The cultural heritage of Lebanon is the cultural heritage of all humanity.

Valery Freland, ALIPH executive director

Tyre, equally revered, was a bustling Phoenician port where the rare purple dye from Murex sea snails was once crafted for royalty. The city is home to ancient necropolises and a Roman hippodrome, all of which have helped shape Lebanon’s historical identity.

Valery Freland, ALIPH executive director

Israel’s war against Hezbollah, once the most powerful non-state group in the Middle East, has thus far killed more than 3,200 people and displaced about a million more in Lebanon, according to local officials.

The Israeli military has pledged to end Hezbollah’s ability to launch rocket and other attacks into northern Israel, which has forced around 60,000 people to flee their homes near the Lebanon border.

On Oct. 23, the Israeli military issued evacuation orders near Tyre’s ancient ruins, and began striking targets in the vicinity.

Children displaced by conflict from south Lebanon play in the courtyard of the Azariyeh building complex where they are sheltering in central Beirut on October 15, 2024. (AFP)

The cultural devastation in southern Lebanon and Bekaa is not limited to UNESCO sites. Across these regions, many cultural heritage sites of local and national significance have been reduced to rubble.

“Cultural heritage sites that are located in the south or in the Bekaa and that are scattered all over the place … were razed and wiped out,” said Farchakh Bajjaly.

“When you can see the demolition of the villages in the south of Lebanon … the destruction of the cultural heritage is coming as collateral damage. The historical sites, the shrines or the castles, aren’t being spared at all.”

Tebnin/Toron castle in southern Lebanon (Shutterstock)

As a signatory to the 1954 Hague Convention, Lebanon’s heritage should, in theory, be protected from harm during armed conflict. However, as Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada has appealed to UNESCO, these symbolic protections, like the Blue Shield emblem, have shown limited effectiveness.

In response to the escalation, the Geneva-based International Alliance for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Conflict Areas, known as ALIPH, has provided emergency funding to Lebanon, working alongside Biladi and the Directorate General of Antiquities.

With $100,000 in initial funding, ALIPH is sheltering museum collections across Lebanon and providing safe accommodation for displaced heritage professionals.

Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, a Lebanese archaeologist and founder of the non-governmental organization Biladi.

“We are ready to stand by our partners in Lebanon, just as we did after the 2020 Beirut explosion,” Valery Freland, ALIPH’s executive director, told Arab News.

“Our mission is to work in crisis areas… If we protect the cultural heritage now, it will be a way (to stop this becoming) another difficulty of the peacebuilding process.”

Documentation has also become a critical tool for preservation efforts, particularly for sites at risk of destruction. Biladi’s role has been to document what remains and, where possible, secure smaller objects.

A man checks the destruction at a factory targeted in an overnight Israeli airstrike in the town of Chouaifet south of Beirut on September 28, 2024. (AFP)

“Unfortunately we are not able to do any kind of preventive measures for the monuments for several reasons,” said Farchakh Bajjaly.

“One of the most obvious ones is due to the weapons that are being used. If the hit is a direct hit then there’s no purpose of taking any action. Nothing is surviving a direct hit.

“The only measures that we can do, as preventative measures … (are) to secure the storage of museums and to find ways to save the small items and shelter them from any vibrations and make sure storages are safe and secure.”

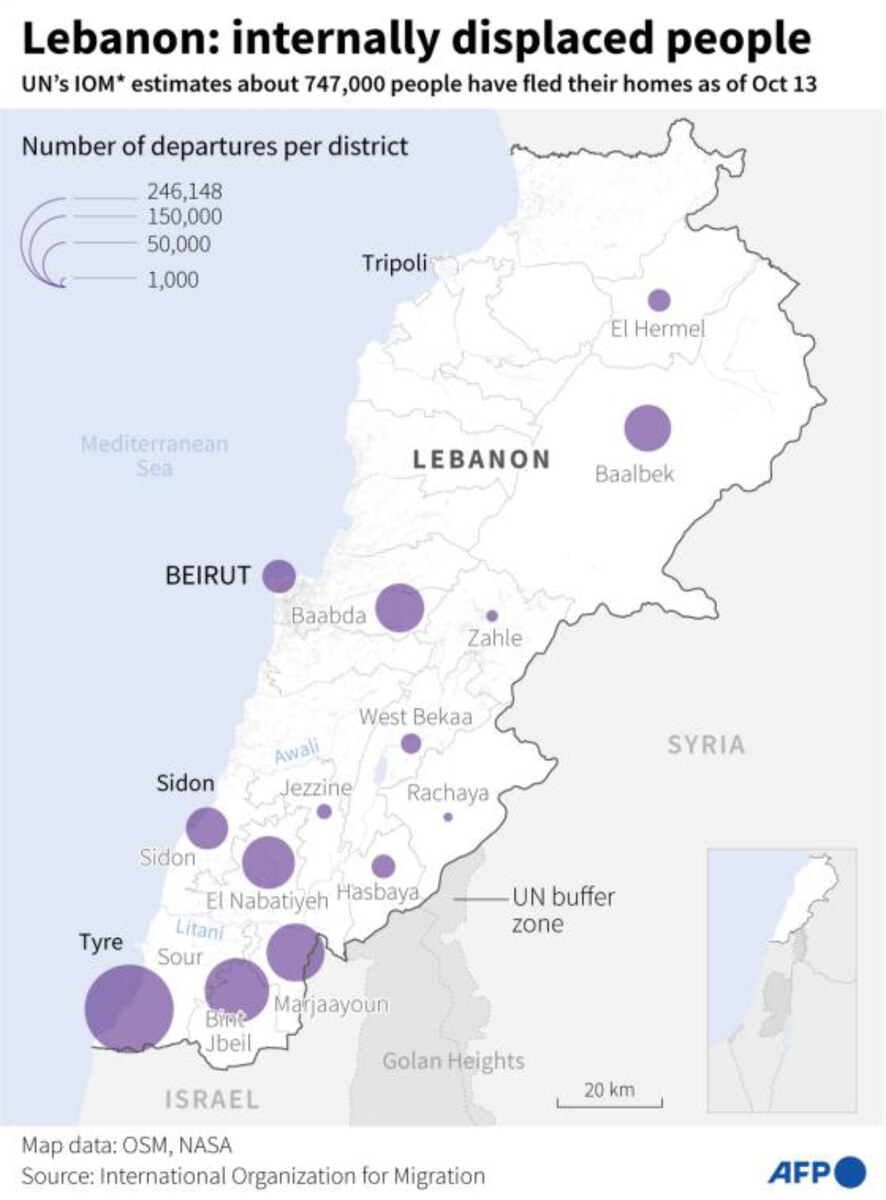

Map of Lebanon showing the number of people who have fled their homes by district as of October 13, according to the International Organization for Migration. (AFP)

Farchakh Bajjaly describes a “dilemma of horror” arising from the conflict. When the IDF issued its evacuation order for Baalbek, around 80,000 residents fled, with some seeking refuge within the temples themselves.

“The guards closed the gates and didn’t let anyone get in,” she said, explaining that, under the 1954 Hague Convention, using protected sites as shelters nullifies their protected status. “If people will take refuge in the temples, then it might be used by the Israeli army to target temples. Thereby killing the people and destroying the temples.”

The displacement of Baalbek’s residents has added to Lebanon’s swelling humanitarian crisis. With more than 1.2 million people displaced across the country due to the conflict, the city’s evacuation order has compounded local instability.

Historic ancient Roman Bacchus temple in Baalbek, Lebanon. (Shutterstock)

Despite the harrowing reality, Farchakh Bajjaly insists that preserving cultural heritage is not at odds with humanitarian goals. “Asking to save world heritage is in no way contradictory to saving people’s lives. They are complementary,” she said.

“It’s giving people a place to find their memories, giving them a sense of continuity when in war, usually, nothing remains the same.”

UNESCO has been actively monitoring the conflict’s impact on Lebanon’s heritage sites, using satellite imagery and remote sensing to assess visible damage.

Arch of Hadrian at the Al-Bass Tyre necropolis. UNESCO world heritage in Lebanon. (Shutterstock)

“UNESCO liaised with all state parties concerned, reminding (them of their) obligations under the 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage,” Nisrine Kammourieh, a spokesperson for UNESCO, told Arab News.

The organization is preparing for an emergency session of the Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property to potentially place Lebanon’s heritage sites on its International List of Cultural Property under Enhanced Protection.

The importance of cultural preservation extends beyond mere aesthetics or academic interest. “It’s part of the resilience of the population, of the communities and it’s part of a solution afterward,” said ALIPH’s Freland.

Elke Selter, ALIPH’s director of programs, believes “protecting heritage is essential for what comes after. You cannot totally erase the traces of the past.”

Indeed, the preservation of Lebanon’s cultural heritage is as much about safeguarding identity and memory as it is about recovery.

“Imagine that your town is fully destroyed and you have to go back to something that was built two weeks ago; that is very unsettling in a way,” Selter told Arab News, noting that studies have shown how preserving familiar landmarks fosters a sense of belonging after displacement.

In the broader context of Lebanon’s recovery, cultural heritage can play a key role in economic revitalization, particularly through tourism.

“For Lebanon’s economy, that’s an important element and I think an important one for the recovery of the country afterwards,” said Selter. “Cultural heritage in Lebanon was one of the key reasons why people would visit Lebanon.”

The tragedy facing Lebanon’s heritage is also a global concern. “The cultural heritage of Lebanon is the cultural heritage of all humanity,” said Freland.

For Biladi and other heritage organizations, Lebanon’s current crisis offers a test of international conventions that aim to protect heritage in times of conflict.

“If the conventions are being applied, then cultural heritage will be saved,” said Farchakh Bajjaly. “Lebanon has become in this war a sort of a field where it’s possible to test if these conventions work.”