KARACHI: Slogans echo from the crowd gathered outside the historic 19th-century Victorian-style, double-story building on Sarwar Shaheed Road in the heart of Karachi. Inside, a conference is underway— one of many events that have transformed this once-quiet haven for journalists into a dynamic hub of activism and dissent.

This is the Karachi Press Club (KPC), often called the “Hyde Park” of Pakistan, and an iconic institution in the country’s largest city.

Founded in 1958, KPC is one of Pakistan’s oldest and most influential press clubs, serving as a gathering point not only for media professionals but also for writers and intellectuals. Frequently described as a symbol of press freedom, the club has long been a refuge for journalists seeking solidarity, especially during times of political upheaval and censorship.

“The Karachi Press Club turned into an institution because it became the voice of dissent,” Mazhar Abbas, a veteran journalist and former secretary of the club, told Arab News, recalling how it evolved from a space for journalists “to sit, share their notes and enjoy tea or coffee” into a center for protests.

Arab News’ Naimat Khan (left) and senior photojournalist Zahid Hussein enter Karachi Press Club in Karachi, Pakistan, on October 30, 2024. (AN photo)

“Irrespective of whether it was a civilian or military government [in Pakistan], the press club became the voice for those whose voices couldn’t make it to the media,” he added. “It raised its own voice against restrictions imposed on it and provided a platform for political parties facing bans.”

KPC truly emerged as a hub of democracy and dissent during the 1970s and 1980s, especially under the military rule of General Zia-ul-Haq, when Pakistan experienced strict censorship and widespread crackdowns on freedom of expression.

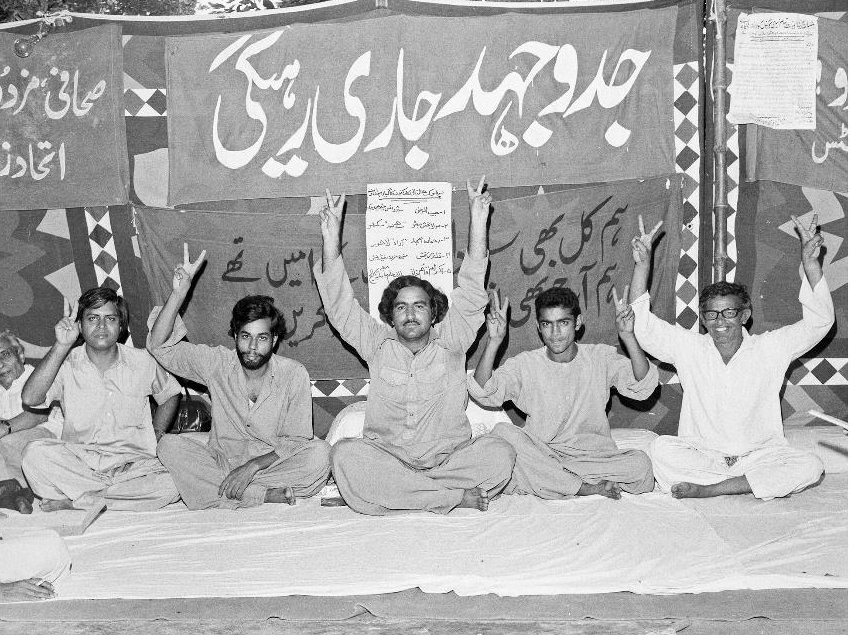

Journalists sit at a camp during their hunger strike at the Karachi Press Club in 1978, during a movement by the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) against the crackdown on newspapers and journalists by then-military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq. (Zahid Hussein/ Arab News)

The club became a stronghold for journalists, activists and intellectuals advocating for democratic principles and press freedom, organizing protests and sit-ins and often risking personal safety.

A.H. Khanzada, a senior journalist and former club leader, recalled how a minister in the Zia regime labeled KPC “enemy territory” for amplifying the voices of the opposition.

“A journalist quipped in response, ‘No, sir, this is not enemy territory; this is the most liberated area,’” he said with a hint of pride, adding that KPC had since been “a symbol of democracy.”

The picture shared by the Karachi Press Club administration on November 1, 2024, shows members of the Karachi Union of Jouranalists protesting against press freedom in Karachi, Pakistan. (Karachi Press Club/ Arab News)

Khanzada remembered the time when it was difficult for politicians to gather, but the club opened its doors, allowing historic meetings by the Movement for Restoration of Democracy, a major political alliance against the Zia regime, which was formed in 1981.

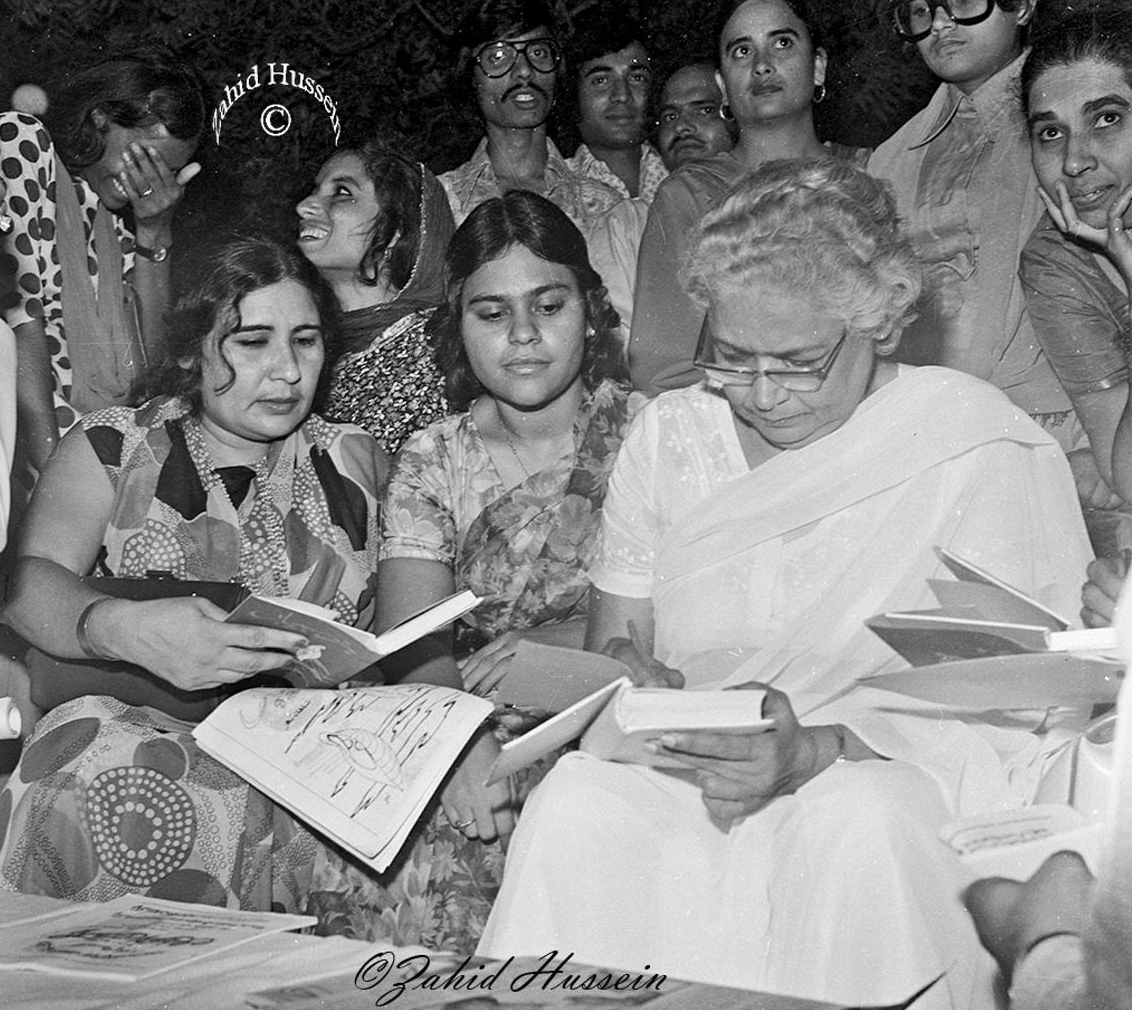

He recalled how Nusrat Bhutto and Kulsoom Nawaz Sharif, the wives of two former Pakistani premiers from rival political factions, held gatherings inside the club when they faced significant state pressure.

Kulsom Nawaz (in green), wife of Pakistan's former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, is pictured at Karachi Press Club in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN photo)

Kulsom Nawaz (left), wife of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, Maryam Nawaz Sharif (center) are pictured at Karachi Press Club in Karachi, Pakistan. (AN photo)

KPC also provided space for leaders of Pashtun and Baloch rights movements to voice dissent and freely express grievances amid extreme pressure.

Shoaib Ahmed, the club’s secretary, said KPC had not only supported democratic forces in Pakistan but also practiced democracy within its walls, noting that its own elections had been held regularly since its inception.

These elections produce a 12-member governing body led by a president and a secretary, which manages the club’s administration and provides various services to over 1,800 members and their families.

“We conduct workshops and awareness sessions, and we provide medical facilities for our members,” he said, adding that the club has a computer lab and digital studio to assist journalists in their work. The facility also features a gym and indoor games.

Fan crowd famous Urdu novelist Ismat Chughtai (right) during her visit to Karachi Press Club in Karachi, Pakistan, in December 1976. (Zahid Hussein/ Arab News)

KPC now has over 150 women members, most of whom have joined in recent years and benefit from a dedicated complex for female members, offering a place to rest and work.

“To enhance women’s development and skills, various workshops and programs are also organized here,” Mona Siddiqui, a governing body member, said.

While women have held various positions within the club, Siddiqui expressed her hope that more of them would assume leadership roles, including those of president and secretary, in the coming years.

“We too will strive to maintain the identity of this club and uphold the principles of freedom of expression, following in the footsteps of our predecessors,” she said.