KETI BANDAR, Thatta: Fatima Hanif was just a teenager when she and her family sought refuge in Baghan, a town in the southern Pakistani district of Thatta, after a devastating sea storm hit their village, Hasan Utradi, near the Keti Bandar port in 1999. The storm claimed around 400 lives across the coastal belt in Pakistan’s Sindh province, depriving thousands of their homes and valuables.

In June last year, authorities issued an alert regarding Cyclone Biparjoy and Hanif, now in her 40s, rushed to the same town along with her husband and son to seek refuge. However, their village and the coastal belt of Sindh were largely spared this time, thanks to the expanded mangrove forests along the coastline in the southern Sindh province.

“Twenty-five years ago, when these [forests] weren’t here, our houses were flooded,” Hanif said, gesturing to the mangroves lining along her coastal village. “Now that these are here, our houses are saved, and we ourselves remain safe too.”

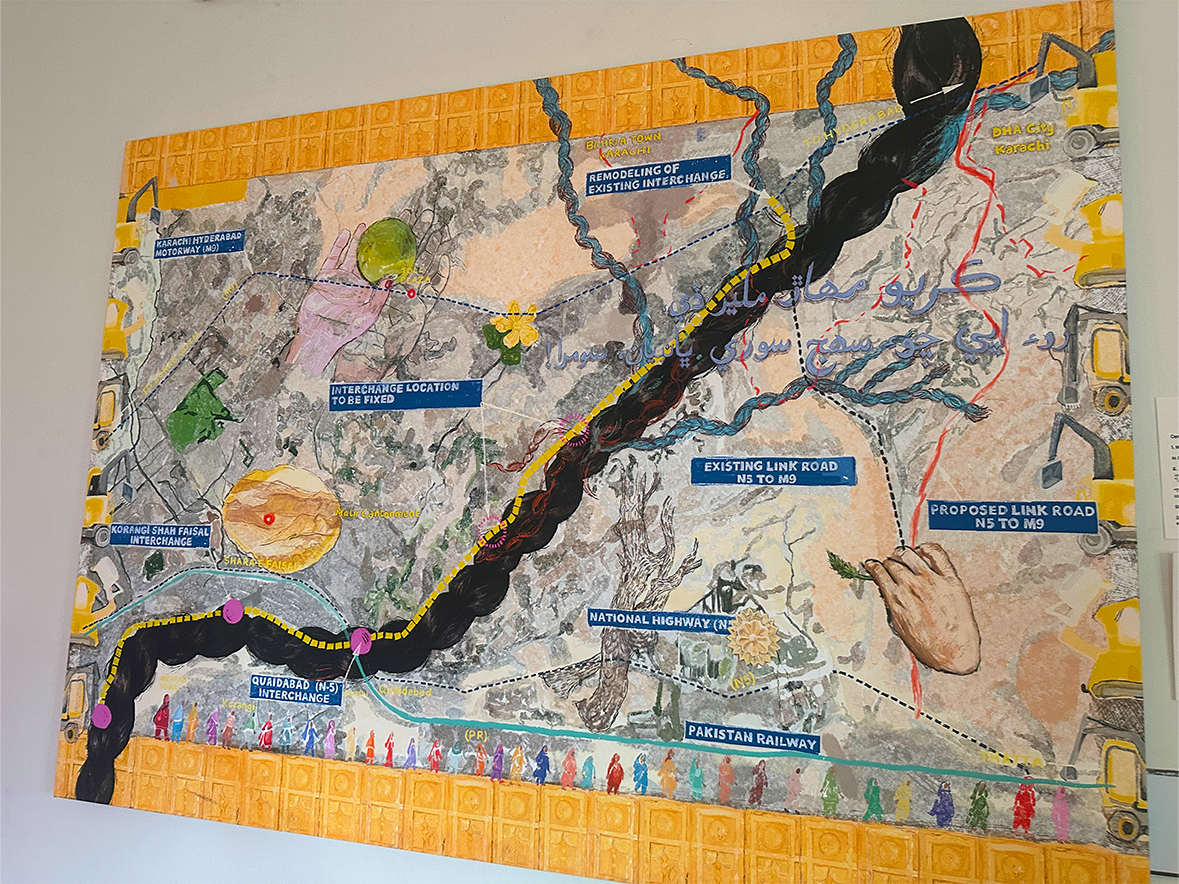

Hanif’s village lies in the Indus River Delta — a low, flat triangular piece of land where the river splits and spreads out into several branches before entering the Arabian sea. The Indus delta has 17 creeks starting from Qur’angi area in Pakistan’s largest city of Karachi to Sir Creek on the Pakistan-India border to the east.

Spanning over 600,000 hectares, the Indus delta ranked as the sixth largest in the world and was flourishing around a century ago, with 260,000 hectares, or 40 percent of the area, covered in mangroves. But this cover drastically reduced to 80,000 hectares due to the low inflow of fresh water from the Indus River due to the construction of several dams and barrages, according to Riaz Ahmed Wagan, chief conservator of the Sindh Forest Department.

Due to this decline in flow of fresh water, Sindh forest authorities launched an extensive reforestation drive in the 1990s and planted harder, salt-tolerant mangrove species such as Avicennia marina, Aegiceras corniculatum, Rhizophora mucronata and Ceriops tagal. As a result, the Indus delta now boasts the largest arid climate mangrove forests in the world.

“From 260 [thousand hectares], it reduced to 80,000 [hectares] and now from 80,000 [hectares], we have currently made it up to 240,000 [hectares]. So, we are nearly about 33-34 percent of the overall delta,” Wagan told Arab News.

“We hope that at least 500,000 hectares in all can be restored through manmade efforts and we hope that by the year 2030 we will be able to reach that landmark.”

Currently, Sindh Forest Department workers have been planting mangrove propagules in a nursery near Keti Bandar, an ancient town that has been rebuilt several times after being submerged by seawater, according to Muhammad Khan Jamali, the Keti Bandar range forest officer.

“When the off-season [from October till February] arrives, we transport them from here to the plantation areas ahead, where they are planted,” Jamali told Arab News as he monitored the process in the nursery.

Ameer Ahmed leads a team of 150 workers who have been diligently planting 80,000 propagules a day in Dabo Creek, some 20 nautical miles from Keti Bandar.

“We lay down a rope and plant [propagules] at 10-feet intervals,” Ahmed told Arab News, placing a rope for his team to follow. “There are 150 of us and we plant 80,000 plants daily.”

The precise pattern, visible from a drone camera, highlights the effectiveness of this manmade effort to restore mangrove forests after decades of reduced freshwater inflow hindered their natural growth.

“Some have matured, some are still premature, and we are planting new saplings, so they are small,” Jamali said, explaining the difference in size of mangrove patches across the delta.

But the reduction water inflow was not the sole reason behind mangrove deforestation and the cutting of these plants for firewood also affected the forests in the Indus delta.

As vigilant forces ensure that no one cuts the plants, coastal communities have also been involved in efforts to protect the forests.

“Cutting of the mangroves is totally banned and we are actively monitoring through our personnel that no mangrove cutting should be undertaken,” said Captain Nehman, an officer of the Pakistan Navy.

He said the navy had partnered with the forest department and local police to protect the mangroves. “We are also engaging the local community to educate them about the importance of the mangroves because these are acting as the lungs of our ecosystem,” Nehman added.

Hanif, one of the aware citizens, said she doesn’t allow anyone near the mangroves close to her home.

“We don’t even let them touch these. Neither do we cut them ourselves, nor we let others do,” she said. “When a sea storm comes, it’s this very [plant] that saves us.”

In Pakistan’s Sindh, mangrove forests shield vulnerable coastal communities against sea storms, hurricanes

https://arab.news/cyka7

In Pakistan’s Sindh, mangrove forests shield vulnerable coastal communities against sea storms, hurricanes

- Indus River Delta in Pakistan, world’s sixth largest, spans 600,000 hectares and extends from Karachi to Sir Creek near Indian border

- Mangrove forests in delta have seen massive growth in two decades, recovering from severe reduction caused by decreased freshwater inflow