DUBAI: The fourth in this year’s series focusing on contemporary Arab-American artists in honor of Arab-American Heritage Month.

Born in Basrah to an Iraqi father and a Palestinian mother, Sama Alshaibi is an Arizona-based professor and artist who has mostly devoted her 20-year career to video, photography and performance art.

During the Iran-Iraq war of the Eighties, Alshaibi and her family moved around the region, living in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan, before eventually settling in the American Midwest when she was 13 years old.

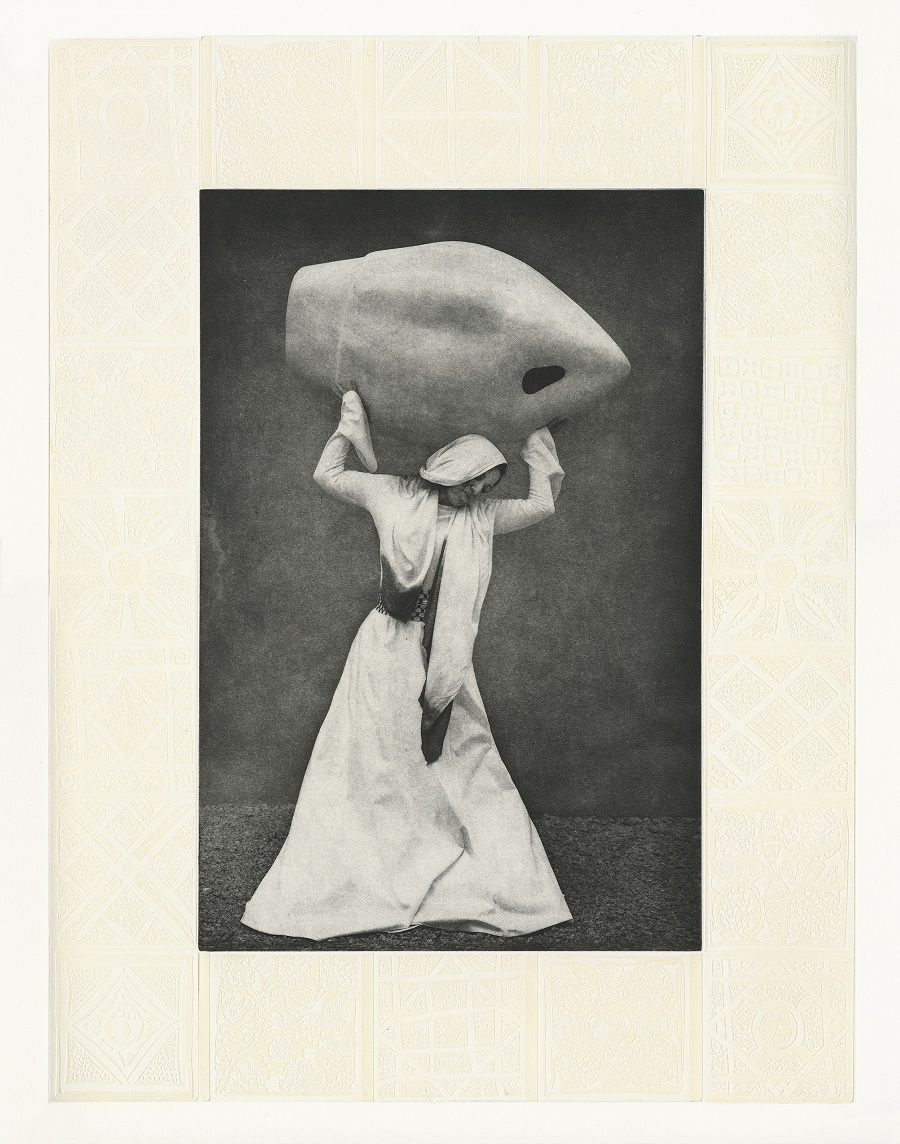

Sama Alshaibi_Water Bearer II. (Supplied)

“Growing up in the United States was strange. We were a ‘different’ family in Iowa and there wasn’t a lot of diversity. But I grew up in a place with nice people,” Alshaibi tells Arab News from Bellagio, Italy, where she is doing a residency at the Rockefeller Foundation.

But she also says there were obstacles, mainly formed by major political events that impacted her. “It was challenging, because of where I’m from,” she says.

Alshaibi’s work is largely inspired by her Arab roots. “Arts were so revered in my family,” she says. “I don’t even know if I would be making art if it wasn’t for my heritage.” It was her father, an avid photographer, who taught her to use a manual camera. She aspired to become a photojournalist herself — inspired by 20th-century African-American photographers, notably Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who documented Black culture in their imagery.

Sama Alshaibi's 'Gamer Albumen' print. (Supplied)

Many of her images are portraits of herself wearing, for example, traditional Middle Eastern garments, referencing romanticized Orientalist portrayals of women, and in the end, challenging them.

“I’m trying to change this idea of what you think an Arab woman is,” she explains. “I started seeing the power of communication, of taking political or social issues and using your body, your performance, your environment, to address them.”

One of Alshaibi’s best-known series is called “Carry Over,” in which she photographed herself carrying large objects (or Orientalist props), such as a tower of container tins or a water vessel, above her head. The images poetically show a woman’s endurance and comment on a collective history, affected by colonialism and cultural loss.

“I’ve always been interested in the notion of ‘aftermath’ — what happens after the destruction of your environment,” explains Alshaibi. “It gets you to the question of what we can’t hold onto anymore.”