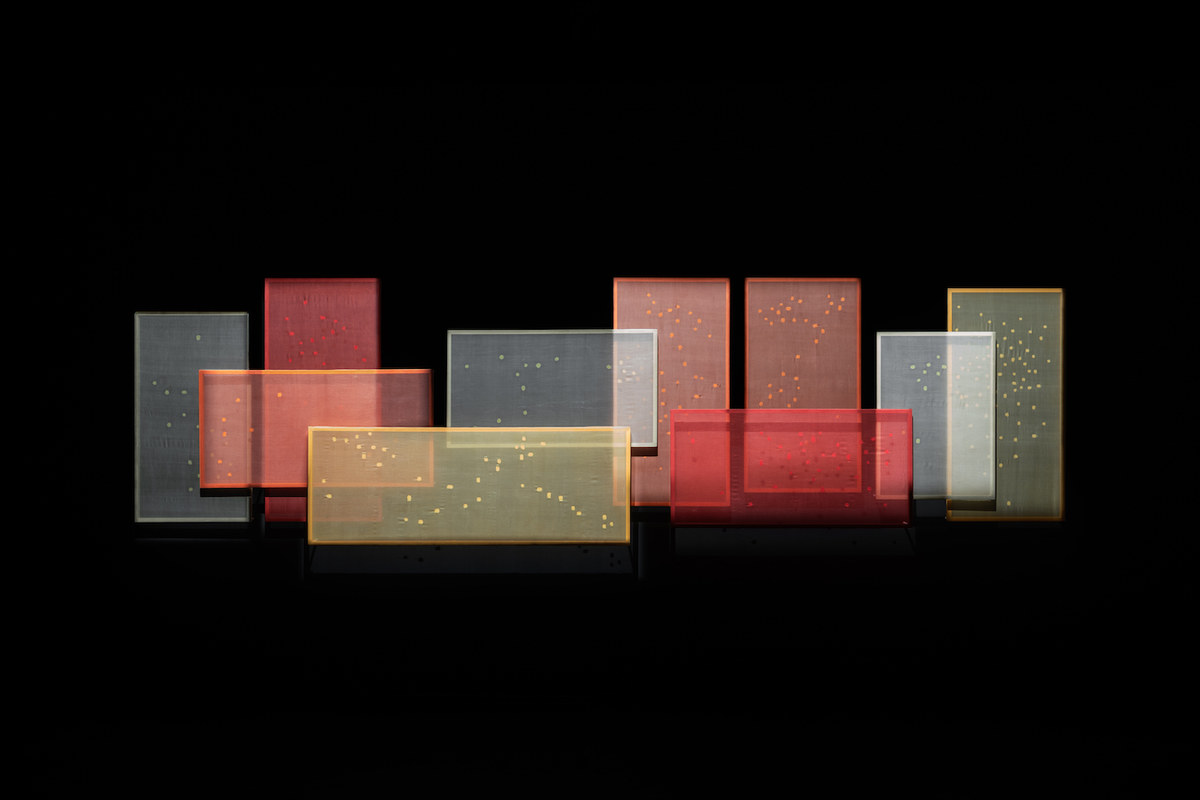

DUBAI: At the Diriyah Art Biennale, Saudi-born artist Dana Awartani, who is of Palestinian heritage, has created a dreamy, otherworldly series of 10 silk fabrics in earthy hues of ochre, reds and greens placed on wooden frames and mounted on the wall as overlapping, semitransparent panels.

The installation — “Come, Let Me Heal Your Wounds” — was derived from research into Ayurvedic dyeing, which is used to create clothing with alleged healing properties. To create the work, Awartani collaborated with artisans in Kerala, India.

The artist also identified 355 cultural sites that have been destroyed because of conflict and violence since 2010 in Syria, Tunisia, Libya, Iraq, Egypt, and Yemen. She marked each location with a tear in the silk, creating her own intuitive map of loss. Together with local craftspeople, Awartani then repaired the fabric, mending each hole by hand.

Dana Awartani, “Come, Let Me Heal Your Wounds” (2020), as presented at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024. (Supplied)

The work hints at the fragility of cultural sites throughout the Middle East and North Africa region, and serves as a plea to safeguard ancient monuments and Arab culture and tradition in general.

“You have this erasure of history that’s happening in the Levant, in Gaza now, and I felt it was critical to use my traditional arts training and aesthetic language to talk about issues that are relevant to the region,” Awartani tells Arab News.

Awartani’s work, which covers a variety of mediums — including drawing, painting, textiles, multimedia installations, and film — is inspired by the rich heritage of Islamic art, particularly ‘sacred geometry’; abstraction; and traditional crafts. She combines these influences with contemporary styles to render works imbued with both alluring aesthetic qualities and philosophical depth. Much of her work uses locally sourced materials, as well as vernacular and ancient design styles to present a dialogue between the past and present of Arab culture.

(Supplied)

“The memories and experiences of the people I collaborate with also become part of the work,” she says, adding that traditional arts “are dying out, people don’t use sacred geometry anymore; people don’t work with their hands anymore.”

Geometry is at the center of her animated film “Listen to my Words” — also on view in “After Rain.” In it, a gray background is gradually filled by a delicately rendered geometric pattern inspired by jali and mashrabiya — latticed screens used in traditional architecture to regulate light, airflow, and heat. Jalis were also used to shield women from the male gaze.

The film, Awartani explains, was inspired by the story of Nur Jahan, the wife of a Mughal emperor, who reportedly played a leading role in government in the 17th century from behind a jali, whispering commands to her husband. It is soundtracked by contemporary recitals of Arabic poetry written by women centuries ago — giving them a platform, and resonance, in the present.

Awartani's 2023 work 'When the Dust of Conflict Settles,' for which she collaborated with stonemasons from Syria. (Supplied)

The incorporation of traditional practices into contemporary artistic discourse is central to Awartani’s art — she is currently pursuing an Ijazah certificate in Islamic illumination. The work she created after earning her master’s degree from The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London focused heavily on sacred geometry; something that is still a major influence (as evidenced by “Listen to my Words”), but less so than it was — a shift she attributes to “recent events in the Middle East, with the ways the current wars have destroyed the heritage and culture of the region. This has really shifted my perspective.”

Of her earlier work, she says: “When I graduated from the Prince’s School, it was hard to snap out of the training because you’re continuing an art form that has been around for centuries, and there’s a certain level of responsibility that comes with that.

“There are many people who take something old, like traditional crafts, and innovate without understanding it. Sometimes I find that problematic. For the longest time, I was still trying to hone my skills and learn as much as I could about traditional arts while still using it in a contemporary way through concepts relating to Islamic geometric patterns.”

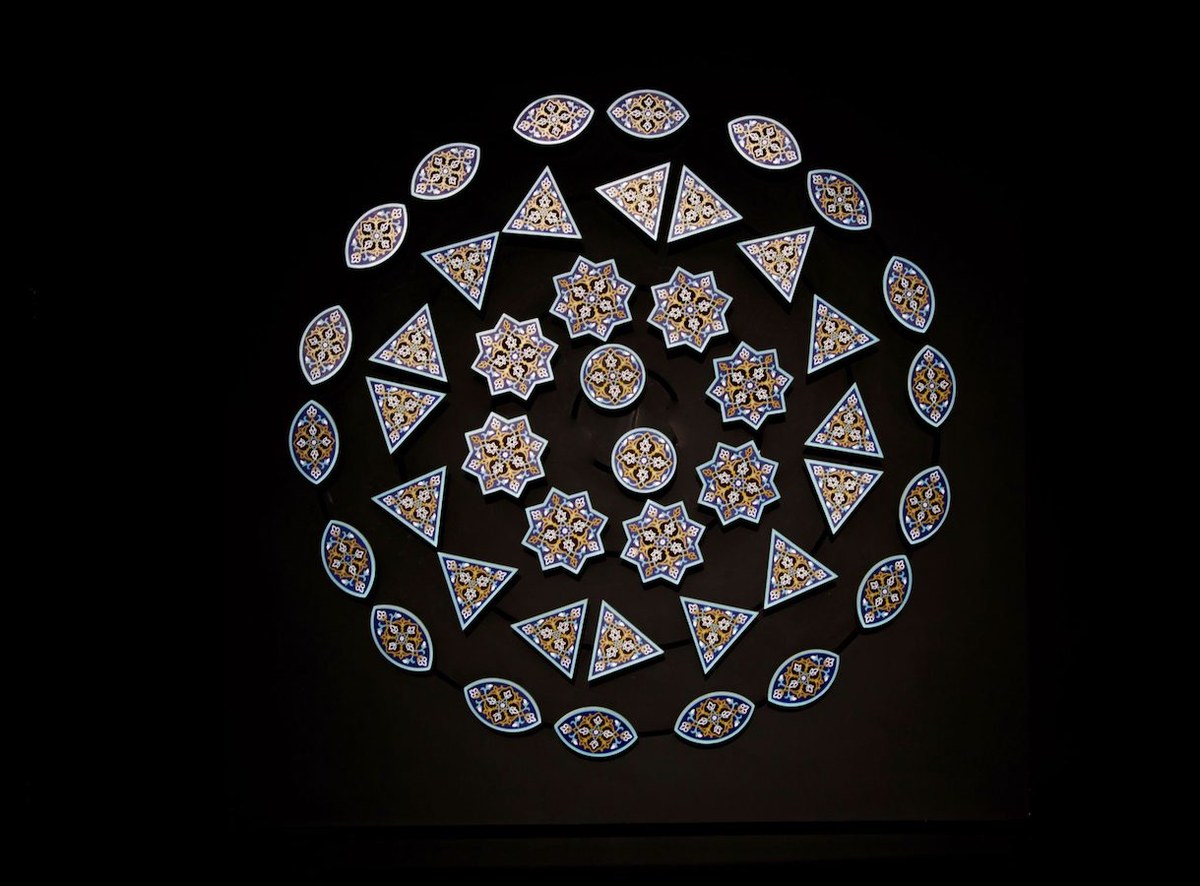

All Heavenly Bodies Swim Along, Each in its Orbit, Dana Awartani, 2016. (Supplied)

Awartani first became interested in sacred geometry, she says, as a way to “understand the world from a different perspective by seeing harmony in nature and the cosmos through the lens of geometry and numbers.” Sacred geometry is also a way to connect with her heritage.

“As Arabs, we’re raised around this fine art, we’re surrounded by it in every corner, but we’re not aware of it,” she told Arab News in a 2014 interview. “You can see geometry all around you, like in mosques for example. I was looking for a track to follow — deep down inside I felt a yearning for it. There is an inner and outer beauty telling a story behind every structured piece; there is no randomness when it comes to creating such pieces.”

It is not only the theoretical side of Awartani’s work that has shifted — the way she creates it has also changed in recent years.

“It’s a lot more collaborative now, involving different craft communities,” she explains. “Whereas, before, I used to predominantly do paintings and works on paper, now I incorporate the work of traditional craftsmen in my work.”

In last year’s “When The Dust of Conflict Settles,” for example, she worked with apprentice stonemasons from Syria who have been displaced by the war in their homeland and are living in Jordan.

“It’s this coming together of various craftspeople to foster an exchange of knowledge that I am really passionate about now,” she says. “This exchange of knowledge and exchange of culture.”