ALULA: “We are in the presence of deep times,” says Lebanese art specialist Maya El-Khalil, sitting against a breathtaking backdrop of golden-brown rock formations in the far distance in AlUla. El-Khalil and her Brazilian colleague Marcello Dantas are the curators of the third edition of Desert X AlUla — an open-air show of 15 monumental sculptural art installations in the ancient Saudi desert.

Spanning three locations, including the up-and-coming ‘cultural destination’ of Wadi AlFann, the show — “In The Absence of Presence” — asks viewers to look beyond the physical in this mystical landscape.

“Rather than presenting work that addresses the monumentality of the desert, we wanted to approach this edition by maybe focusing on what cannot be seen — what’s invisible to all of these forces,” El-Khalil tells Arab News. “As humans, we’re nothing when you look at this place’s sense of deep time.”

Seventeen artists are taking part in the exhibition, several from the Gulf and the wider Arab world, including Monira Al-Qadiri, Faisal Samra, Kader Attia, Rand Abdul Jabbar Ayman Yossri Daydban, and Caline Aoun. For their site-responsive works, some artists were inspired by historical narratives, while others delved into poetry, philosophy, nature and performance art.

“We urged artists to really engage with the landscape with questions and uncertainty rather than certainty,” says El-Khalil.

So, why have this “light intervention,” as El-Khalil puts it, in an ancient site where protection is a top priority?

“Probably there is this element of creativity,” she says. “I think it’s quite natural. . . There is creativity in nature and human beings respond to that. It is really about leaving no trace, as much as possible. Having said that, we have a trace of the passage of time, traces of civilization and of the rock art that you see. These are windows into the past that have been left for us to enjoy and learn from.”

Here are seven highlights from Desert X AlUla, which is free to the public and runs until Mar. 23.

FILWA NAZER

‘Preserving Shadows’

The Saudi artist designed an elevated bridge-like installation, topped with high black triangles that are meant to give a sense of “fear and hostility in relation to the nature of the desert,” Nazer explained during a press tour. “There’s an ancient belief, even from before Islam, that there are ‘jinn’ or spirits that reside in the shrubs of the desert. I read an account of two men that were sitting in the desert and they lit a fire in the shrub. Snakes flew out of the shrub and they attacked and killed them. Growing up in ‘previous Saudi’ we heard stories about jinn in this part of the country, and it kind of contributed to the fear of not having accessibility to it.” The work resembles “the body of a petrified skeleton of a snake and it’s meant to feel, as you approach it, like you are walking through a journey of shadows and then you reach the end of the ramp — a metaphor for overcoming a dark journey,” she said.

MONIRA AL-QADIRI

‘W.A.B.A.R.’

In the 1930s, a British explorer — Harry St. John Philby — was looking for Ubar, an ancient city known as the ‘Atlantis of the Sands’ in the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Peninsula’s desert. There, he was shown what locals claimed were ‘black pearls.’ It was later discovered that they were, in fact, meteorites from outer space. Philby named them ‘Wabar’ pearls. This little-known story is the inspiration behind Kuwaiti artist Al-Qadiri’s installation, ”W.A.B.A.R.” It consists of five large black spheres, made of bronze, scattered on the sand.

“It’s a story of disappointment and human imagination,” Al-Qadiri says. “That you could find these small items in the middle of the desert and make this huge story from them about a people and pearls. This is why I exaggerated the size of the objects.”

FAISAL SAMRA

‘The Dot’

The Bahraini-born Saudi artist presents a trail of rocks lead to the titular large reflective sphere, which stands in a small valley. “The aim for me was for the audience to come and complete the work. It will not be completed without the audience,” Samra says. “I want the audience to live a unique moment of AlUla with this work, which is respecting the environment.” The simple shape is a symbolic one, representing a “trace of a second,” a moment in time, a grain of sand. “The accumulation of dots is the accumulation of moments,” he adds. It also demonstrates how a small dot can be physically impactful — like the drops of rain that, along with the wind, eventually led to the formation of this valley, which was once a single rock.

IBRAHIM MAHAMA

‘Hanging Garden’

The Ghanaian artist is presenting works at all three sites of the exhibition, including this one at AlManshiyah Plaza, located in a historic neighborhood where the AlUla Railway Station is preserved. In the early 20th century, the station was part of the Hejaz Railway, which connected Damascus to Madinah. Mahama’s work is comprised of dangling terracotta pots of the kind used for storing water in Ghanaian communities — a recurring motif in Mahama’s work at AlUla. According to an Instagram post by the event’s artistic director Neville Wakefield, “Mahama asks how we can restore memories we never had before, and how we can use archeology and the scars of history to create new meanings within a landscape.”

RANA HADDAD AND PASCAL HACHEM

‘Reveries’

The Lebanese duo created this trio of intriguing, circular towers made of orange terracotta pots, which stand tall in Wadi AlFann. Viewers can enter the narrow spaces and look up to admire the precise, repetitive pattern the pots form. The project pays tribute to regional heritage and craftsmanship. “Our art, like a gentle breeze, whispers the importance of respect, nurturing a harmonious relationship between humanity and the natural world,” wrote the artists. According to a statement released by Desert X AlUla, the work is also “a testament to the circular economy. . . Light, air, and frankincense flow through, creating sanctuaries for desert flora and fauna.”

SARA ALISSA AND NOJOUD ALSUDAIRI

‘Invisible Possibilities: When The Earth Began To Look At Itself’

The two young Saudi creatives, co-founders of syn architects, carved a geometrical 110-meter-long pathway into the desert, including ledges on which visitors can rest and contemplate their surroundings. “Based on a more poetic criteria of time, memory, materiality, and occupation, the artists believe that this form of intervention raises and intensifies our awareness of the surrounding ecology and creates a place of meaning and contemplation out of a careful reframing of the familiar,” Wakefield explained.

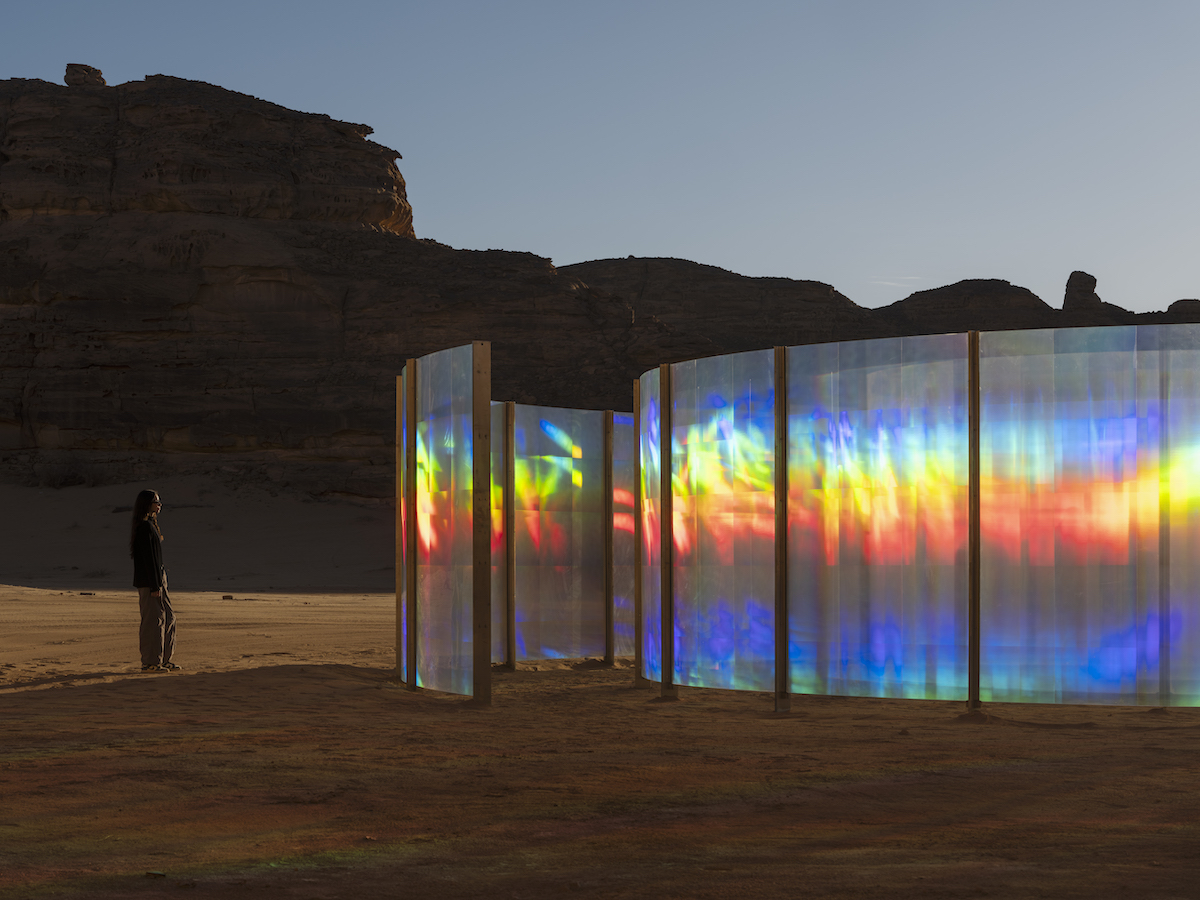

KIMSOOJA

‘To Breathe’

The South Korean conceptual artist explores the ethereal nature of light, often materialized in site-specific installations in eye-catching iridescent tones. Her work in AlUla is “a reflection on a conceptual and geometrical formation of the AlUla desert landscape,” according to a written statement. “It reflects the movement of wind and the passage of light traversing through the spiral path of prismatic glass surface that becomes a fluid, translucent canvas. Sunlight unravels into an iridescent color spectrum, casting rainbow-colored shadows and circular brushstrokes onto the sandy earth. . . A walk in and out of a contained yet open path of spiral unfolds an abstract lightscape that is at once a drawing, a painting, and a sculpture.”