DUBAI: When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020, governments worldwide were caught off guard. Having faced no health emergency of this magnitude in generations, states were left scrambling to protect their populations and shield their economies.

Now that life has largely returned to normal following years of social distancing, travel controls and trade disruption, global health experts are calling on governments to prepare for the next pandemic — ominously dubbed “Disease X.”

Such is the sense of foreboding that the mere mention of “Disease X” — x being the algebraic symbol for the unknown — at this year’s World Economic Forum sparked panic on social media as people took the hypothetical warning literally.

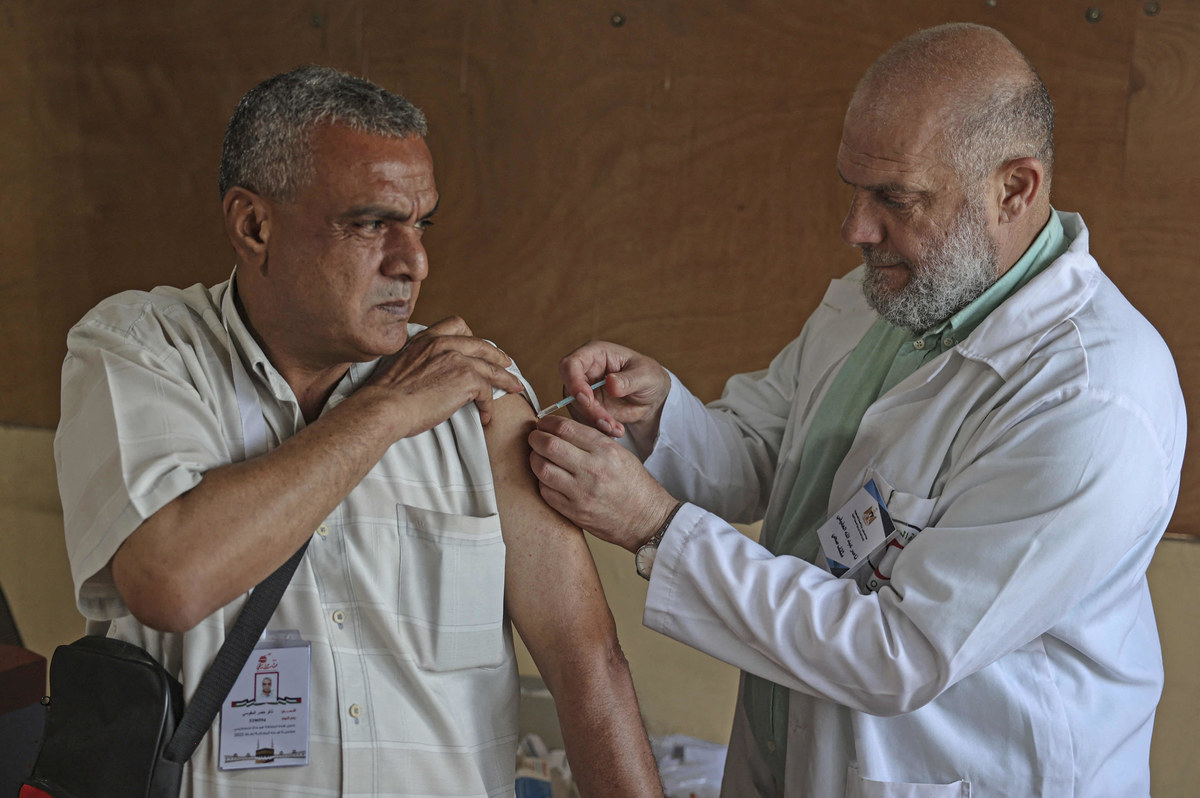

Experts voiced concerns about the likelihood of another pandemic in the future. (AFP/File)

Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Health was forced to issue a statement to allay fears of a new outbreak, clarifying that “Disease X” was merely a placeholder name issued by the World Health Organization to refer to the possibility of a future pandemic.

The ministry also emphasized that cautionary statements from the WHO and scientists were only intended to promote greater global preparedness in the face of new and emerging threats to public health.

“The recurring message year after year is that humans are vulnerable to epidemics due to our coexistence with numerous viruses and germs,” the ministry said.

Indeed, although health experts were not announcing the emergence of a sinister new disease, they were voicing concerns about the likelihood of another pandemic in the future — one that could be even more deadly than COVID-19 and that the world is still ill-prepared for.

“If and when it occurs, it would have the potential to cause death and devastation,” Dr. Fabrizio Facchini, a consultant pulmonologist at Medcare Hospital Al-Safa in Dubai, told Arab News.

According to Dr. Facchini, microbiologists and epidemiologists are concerned that a new virus could emerge in the future which would have a similar impact to the deadly Spanish flu of 1918-20.

COVID-19 killed around 7 million people and infected 700 million. (AFP/File)

To put that in perspective, the Spanish flu, or “Great Influenza,” killed an estimated 50 million people and infected approximately one-third of the global population.

By comparison, COVID-19 killed around 7 million people and infected 700 million as of January 2023, according to WHO figures. The pandemic was officially declared over in May that year, although the virus continues to travel.

“Defining this potential threat as ‘Disease X’ is intended to prioritize preparations for dealing with a disease that would not have vaccinations or medications in place and could cause a significant epidemic or pandemic in the future,” Dr. Facchini said.

INNUMBERS

50m — Deaths from Spanish flu, which infected 33% of the global population (1918-20).

7m — Deaths linked to COVID-19, which infected 700m people worldwide (as of Jan. 2023).

Source: WHO, CDC

Two years into the pandemic, the WHO attributed approximately 1.4 million deaths in the Middle East and Asia to COVID-19. While some nations in the region fared better than others, experts believe there are still lessons to be learned for future outbreaks.

“Although the UAE did well in COVID-19 pandemic preparedness compared with most other countries, there are still steps they should take to prepare for a ‘Disease X’ or other possible epidemics,” Chandulal Khakhar, a Sharjah-based pharmacist, told Arab News.

Khakhar believes hospital capacity is something authorities must examine, considering the “significant strain” experienced by healthcare facilities during the pandemic. Additionally, critical care should be prioritized in health centers and hospitals.

“To do this, healthcare should begin in communities, and preventive care should be done at home,” he said.

Health experts want to see a more joined-up approach to pandemic preparation and response. (AFP/ File)

As the COVID-19 pandemic progressed, technology increasingly played a larger role in everyday lives and healthcare systems.

“Wearable devices to track health progress and community health programs should be launched,” said Khakhar. “And remote checkups such as telehealth should be improved and enforced.”

The number of COVID-19 deaths associated with countries in the Middle East and North Africa relative to other regions remained low during the pandemic, both in total and per capita terms, according to data from the Brookings Doha Center.

This trend may be influenced these countries’ relatively young populations, as well as the robustness of healthcare systems, particularly in Gulf states.

Initially, research showed the highest number of deaths per million population were in Lebanon and Iraq. However, the Gulf states experienced an uptick by June 2020, coinciding with some of the highest infection rates in the region.

By autumn, the Gulf countries reported some of the lowest fatality figures in the region, while numbers rose notably in Iraq, Jordan, Oman and Tunisia amid a second wave of deaths in the late summer.

Still, cumulative deaths have remained low in the Gulf despite many parts of the region having grappled with a surge in fatalities when subsequent waves of the virus strained healthcare systems.

Governments and stakeholders can leverage the potential of mRNA vaccine technology to expedite the development of new vaccines if and when needed. (AFP/File)

This was especially evident for Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia, where the overall number of deaths increased significantly from 2021 onward.

Health experts want to see a more joined-up approach to pandemic preparation and response, in part to make public health outcomes more equitable between wealthy and developing nations.

In a joint statement issued at the WEF, two dozen heads of state called for a comprehensive shift involving all sectors of government and society, forming the basis of a “pandemic treaty.”

Such an approach aims to enhance national, regional and global capacities and resilience in preparation for future pandemics.

FASTFACT

‘Disease X’ is the name given by scientists and the WHO to an unknown pathogen that could emerge in future and cause a serious international epidemic or pandemic.

Because public health and national defense experts are concerned the next pandemic could be even more damaging than COVID-19, Dr. Facchini said it was incumbent on countries to prepare for “whatever biology brings, whether it is from nature, engineering, or a laboratory accident.”

The WHO first introduced the term “Disease X” in 2017 when discussing priority diseases alongside conditions like Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Ebola, Lassa fever, Zika, and then COVID-19, which is considered the first “Disease X” — of more to come.

These viruses were flagged as international priorities, emphasizing the need for states to increase their research and development into their symptoms, spread, treatment and inoculation.

Millions of people have been vaccinated since the emergence of COVID-19, greatly reducing the severity of symptoms. (AFP/File)

WHO researchers anticipate the next “Disease X” will be caused by a new virus derived from one of approximately 25 viral families which have already demonstrated the ability to infect humans.

“The next pandemic pathogen may not be a coronavirus at all. Experts are looking into a range of bird flu strains due to increased transmission to and among mammals, as well as several recent human cases in various parts of the world,” Dr. Facchini said.

Millions of people have been vaccinated since the emergence of COVID-19, greatly reducing the severity of symptoms and improving survivability. However, immunization against this particular coronavirus does not guarantee protection against new ones.

“Coronaviruses have caused some of the most deadly outbreaks in recent decades,” said Dr. Facchini.

These viruses — commonly transmitted from animal hosts to humans and causing fatal respiratory infections — have been observed at least three times this century.

While populations may not be protected against the next “Disease X,” governments and stakeholders can leverage the potential of mRNA vaccine technology to expedite the development of new vaccines if and when needed.

The WHO has already initiated measures in preparation for future outbreaks, Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus revealed at this year’s WEF.

Experts suggest regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight and refraining from smoking as helpful to reducing susceptibility to diseases. (AFP/File)

Proactive steps include the establishment of a pandemic fund and creation of a “technology transfer hub” in South Africa, in part to address vaccine inequity between high and low income countries.

Moreover, Ghebreyesus called on countries to sign the WHO’s pandemic treaty, so the world can better prepare for inevitable future outbreaks.

“The pandemic agreement can bring all the experience, all the challenges that we have faced, and all the solutions into one,” he said.

Regarding the ability to address potential outbreaks effectively, Dr. Facchini stressed the importance of early detection, surveillance and monitoring of possible diseases in both animal and human populations.

“Investing in research and development of new vaccines, global cooperation, public awareness, and education can all help to halt the next pandemic,” he said.

Global health experts are calling on governments to prepare for the next pandemic — ominously dubbed “Disease X.” (AFP/ File)

And, while individuals cannot control every aspect of their health, Dr. Facchini said basic steps can be taken to maximize personal well-being.

These include engaging in regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight and refraining from smoking and other vices which heighten susceptibility to diseases.

“One of the lessons we learnt from the pandemic was that people in less favorable conditions fared worse,” said Dr. Facchini. “Those in worse health bore the burden of hospitalizations.”