DUBAI: The 32-year-old Saudi conceptual artist and curator Meshal Al-Obaidallah tells Arab News there is one central question that serves as the foundation of his practice: “Before it is forgotten, how can our ever-changing present-day culture be preserved? With how things are changing very fast, especially here in Saudi, it’s important for us to remember.”

Al-Obaidallah, who was born in the US and now lives in Riyadh, continues: “You always hear other artists talk about the collective memory of society. But what I’m focusing on is the collective amnesia — things that we tend to forget because we’re changing so quickly.”

Like many others in the creative field, Al-Obaidallah has been surprised by the rapid opening-up of the Kingdom in recent years. “When these changes happened, I was based in the US and when I came back for a visit, I really had, like, a cultural shock,” he says.

Al-Obaidallah's 'Shimagh Series.' (Supplied)

His works explore a combination of digital art, Internet and pop culture, and local references. “I like to look at different ways of archiving and documenting narratives,” he says.

In one of his earlier works, entitled “Shimagh Series,” Al-Obaidallah took the traditional cloth headdress worn by Khaleeji men, and infused it with bright colors, addressing Arab multiculturalism. “It looks at different aspects of the Arab identity and what it means to be an Arab today,” Al-Obaidallah explains.

That interest in experimenting with objects, and thinking about preservation and memory, is ongoing. In late 2023, Al-Obaidallah took part in a group exhibition at the Saudi Arabia Museum of Contemporary Art. He presented an interactive, library-like installation called “IMG_0220: Physical Preservations of a Once Lost-Internet Video,” displaying rows of cassettes, VHS tapes and postcards — all cultural symbols, and important methods of communication, of the Eighties and Nineties. And to keep the project current with the times, QR Codes were installed, through which to download “IMG_0220,” a seven-second video loop of a man talking that used to be on Al-Obaidallah’s old iPhone.

The sound from 'IMG_0220' is stored on functional cassette tapes. (Supplied)

“We have this common misconception that everything stays online forever. But that’s not true, as some media gets lost and deleted,” he says. Aesthetically, the installation has an attractive pearly feel, colored with an iridescent sheen.

“The color is intentional, because I want people to feel like they are inside the Internet,” says the artist. “I want it to be inviting. During the exhibition, people were actually grabbing things off the shelf. They could read, touch and watch the items. It was interactive, not like other museums typically are, where you can’t touch anything. By the end of the day, the entire shelf would be all messed up, which was kind of the whole purpose.”

As our culture becomes more digital-focused, it seems many are still yearning for the concrete and tangible, be it vinyl records or physical books. In a way, one could argue that we are going backwards, culturally.

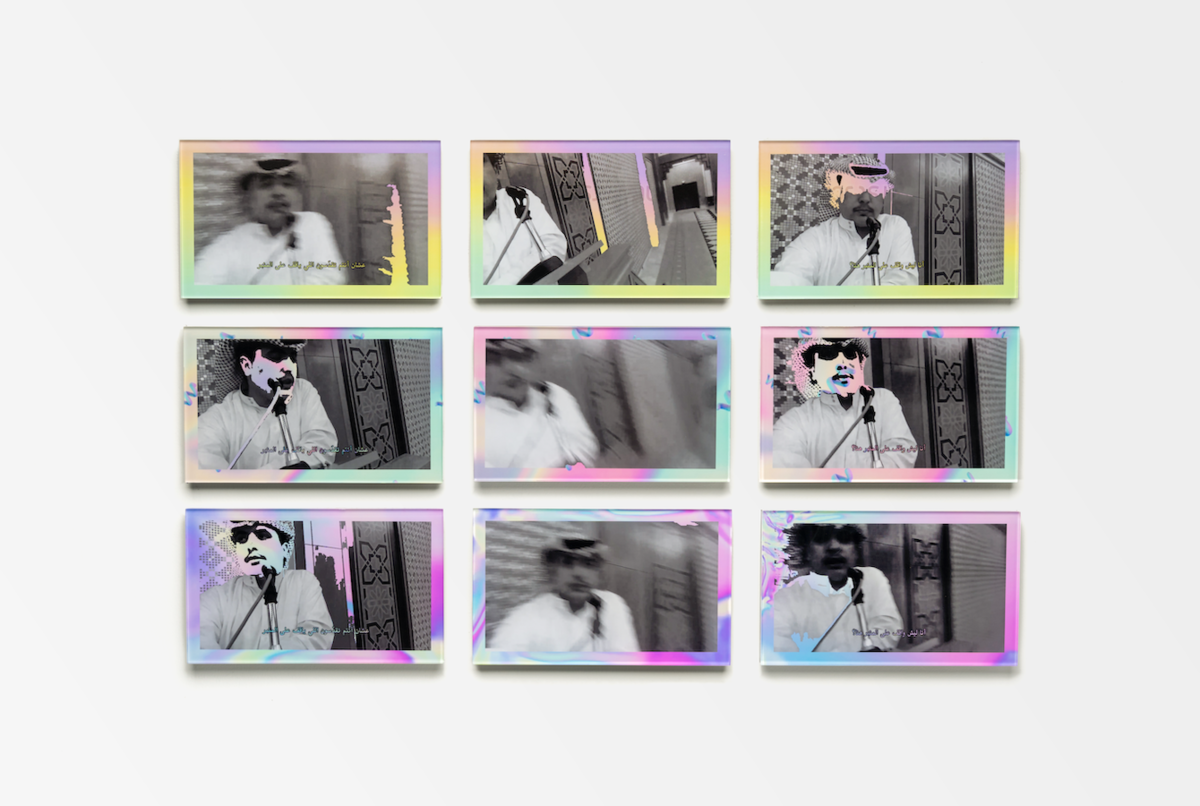

Stills from IMG_0220 are preserved inside sheets of acrylic. (Supplied)

“I think what I’m trying to say is that we shouldn’t just rely on digital aspects. We should also rely on physical things,” says Al-Obaidallah. “It’s not that one is more important than the other; I feel like they complement each other.”

He also believes that today’s social-media culture is a continuation of old-school tools, but advanced and shared at a faster rate. “At the exhibition, more than 1,000 exhibition booklets and 3,000 postcards were given out to people — the same way that we share tweets and Instagram posts and broadcasts online,” he adds.

Now that the work has been uninstalled, Al-Obaidallah still has his boxes of VHS tapes, cassettes, booklets, and postcards. He hopes the project will travel around the world, as he believes it contains a universal theme.

“Even after the exhibition ended, I’ve sent out these booklets and postcards to people in so many countries — the US, the UAE, Kuwait, Jordan and Zimbabwe,” he says. “The whole experience isn’t about the physical work, but more about the sharing that happens.”