DUBAI/LONDON: Israel’s suspected killing of senior Hamas figure Saleh Al-Arouri in Beirut on Jan. 2, followed by the death of Hezbollah commander Wissam Al-Tawil in a similar strike in southern Lebanon on Jan. 8, has once again thrust the country into the midst of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Although Israeli forces and members of Lebanon’s Iran-backed Hezbollah militia have traded fire across their shared border since the conflict in Gaza began on Oct. 7, many fear Israel’s suspected targeting of militia leaders on Lebanese soil could lead to a regional escalation.

Al-Arouri, the deputy chief of Hamas’s political bureau and founder of the group’s armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, was killed in a precision drone strike alongside several of his henchmen at an apartment in a Hezbollah-controlled neighborhood in the south of the Lebanese capital.

Thousands of Hamas supporters gathered to mourn his death and demand retribution. In a live-streamed speech, Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, condemned the killing, describing it as an act of “flagrant Israeli aggression,” and vowed it would not go unpunished.

However, the Hezbollah chief stopped short of declaring war on Israel.

That was before Al-Tawil, deputy head of Hezbollah’s Radwan Force, was also killed in a suspected Israeli drone strike on a vehicle in the southern Lebanese town of Khirbet Selm. He was the first senior Hezbollah figure to die since the conflict in Gaza began.

This undated picture released by Hezbollah Military Media shows senior Hezbollah commander Wissam Tawil. An Israeli airstrike killed Tawil, the latest in an escalating exchange of strikes along the border that have raised fears of another Mideast war even as the fighting in Gaza exacts a mounting toll on civilians. (Hezbollah Military Media, via AP)

Then, on Jan. 9, Ali Hussein Burji, commander of Hezbollah’s aerial forces in southern Lebanon, was also killed in Khirbet Selm in another suspected Israeli airstrike.

So far, the “phony war” between Israel and Hezbollah has been largely confined to reciprocal rocket and drone attacks along the shared border. But if the hostilities escalate, Lebanon could witness a repeat of the devastating 2006 war with Israel — a conflict it can ill afford.

Lebanon’s caretaker government has been at pains to ratchet down the tensions. “Our prime minister continues to dialogue with Hezbollah,” Abdallah Bou Habib, Lebanon’s foreign minister, told CNN shortly after Al-Arouri was killed.

“I don’t think the decision is theirs — referring to Hezbollah — and we hope they don’t commit themselves to a larger war. But we are working with them on this. We have a lot of reasons to think this will not happen. All of us, all the Lebanese, do not want war.”

He added: “We can’t order them but we can convince them. And it’s working in this direction.”

Many Lebanese citizens feel their country is being held hostage by Tehran through its proxies, at a time when they and Lebanon’s many Palestinian refugees are preoccupied with the challenges of daily survival amid an unprecedented and prolonged economic crisis.

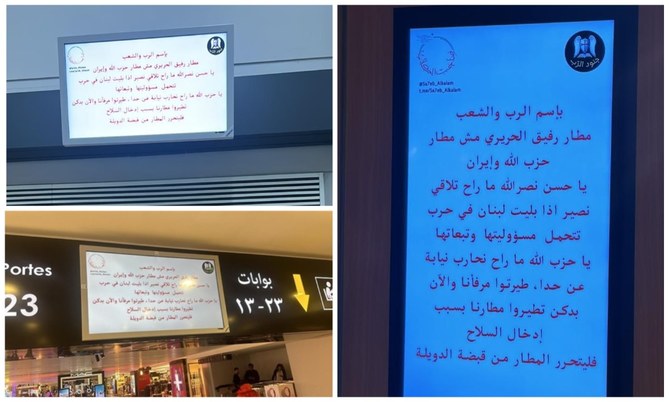

The growing resentment against Hezbollah’s grip on the country was amply demonstrated on Jan. 7 when departure screens at Beirut’s international airport were hacked to display anti-war messages.

“The airport of Rafic Hariri isn’t Hezbollah’s nor Iran’s,” one of the messages read. “Hassan Nasrallah, you will find no allies if you drag Lebanon into war. Hezbollah, we will not fight on behalf of anyone.”

Information screens at Beirut’s main airport were hacked on Sunday with a message to Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. (Screenshots/X)

Alleging Hezbollah’s responsibility for the devastating explosion at Beirut’s port on Aug. 4, 2020, and its role in the import of Iranian weaponry into Lebanon, the message added: “You blew up our port and now want to do the same to our airport by bringing weapons in. May the airport be freed from the grips of the statelet (Hezbollah).”

Anxieties about undue foreign influence in Lebanon have been a recurring theme since the country gained independence from France in 1943, with regional states and armed groups treating Lebanon as a battleground for their own proxy wars.

The Lebanese civil war, which began in 1975 and ended in 1990, was one the bloodiest periods in the country’s history, witnessing a fierce conflict between Christian and Muslim militias who each sought to align themselves with foreign powers.

Even before the civil war, armed groups were using Lebanon as a launch pad for terrorism. In 1971, Yasser Arafat, former leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, made Lebanon his base of operations from which to attack Israel.

Lebanese Christians, concentrated in the eastern part of Beirut and the mountains of Keserwan, resented the Palestinian presence in their country and chose to enter into alliances with Israel and Syria to counter the influence.

Although ostensibly of advantage to Lebanese Christians, Israel’s motives were largely self-serving; at the height of the Lebanese civil war, Israeli forces launched aerial and sea attacks on the PLO in Beirut and southern Lebanon.

In one notorious incident, following the assassination of President Bashir Gemayel on Sept. 14, 1982, Christian militiamen allied with Israel massacred between 800 and 3,500 Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila camps on Beirut’s outskirts.

Israeli troops had sealed off the camp while the militiamen went on their killing spree, targeting unarmed civilians. Despite global outcry, no one has ever been arrested or put on trial for the massacre.

In Israel, an inquiry found a number of officials, including then-defense minister Ariel Sharon, were indirectly responsible.

FASTFACTS

* Saleh Al-Arouri, deputy chief of Hamas’s political bureau and founder of its armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, was killed in a suspected Israeli drone strike in Beirut on Jan. 2.

* Wissam Al-Tawil, deputy head of Hezbollah’s Radwan Force, was killed in a suspected Israeli drone strike in the southern Lebanese town of Khirbet Selm on Jan. 8.

* Ali Hussein Burji, commander of Hezbollah’s aerial forces in southern Lebanon, was also killed in Khirbet Selm by a suspected Israeli air strike on Jan. 9.

Despite the official withdrawal of the PLO from Lebanon in August 1982, Israel took the opportunity to invade the country just two months later with the stated aim of crushing all remaining PLO sleeper cells and bases, and ended up occupying the south until May 2000.

It was amid the chaos of the Lebanese civil war that the Shiite Muslim militia Hezbollah emerged.

Syria, meanwhile, under the regime of Hafez Assad, entrenched itself in Lebanese politics, turning its civil-war-ravaged neighbor into a veritable puppet state, with Hezbollah serving as a junior partner. During this time, Syria had more than 30,000 soldiers stationed throughout the country.

“I remember those days well and clearly,” Walid Saadi, 67, a Lebanese retiree who lived through the civil war, told Arab News. “You felt like you were not living in Lebanon but in Syria.

“The Syrian army had a formidable power in the ‘90s, more than the Lebanese army. They were running amok in the cities and you couldn’t dare tell them anything. Whatever Syria wanted, Lebanon served.”

Saadi said that despite the country experiencing a period of relative peace and economic stability during the 1990s and early 2000s, the older generation continued to feel a sense of humiliation and subjugation to the Syrian presence.

Hezbollah and Israeli forces trade fire on the Lebanese border. (AFP)

“Lots of people went missing during the civil war, lots of them were disappeared by Syrian forces. You cannot ask for their whereabouts. Even if you wanted to, you get no answers. The Syrian regime was, and remains, brutal.”

It was only after the 2005 assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, an outspoken critic of the Syrian regime, that Syria officially withdrew its forces, albeit only under intense international pressure.

Since then, the power of the Syrian regime has vastly diminished as a result of its own grinding civil war, which began in 2011, leaving the regime of President Bashar Assad as little more than a vassal of its remaining international backers, Russia and Iran.

Now, as Israel continues its military operation against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, there are concerns within Lebanese society and the international community that Hezbollah will exploit the crisis by turning Lebanon into a battlefield between Israel and Iran.

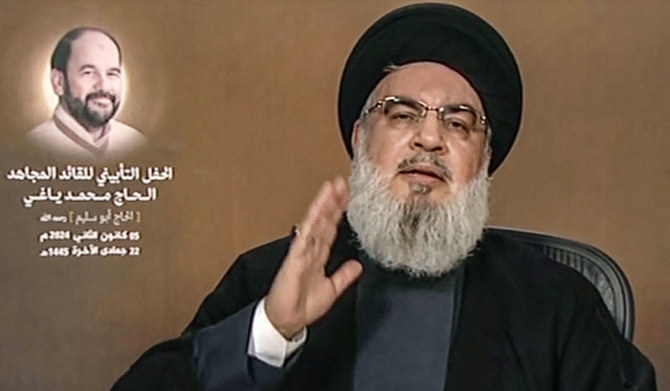

In a speech on Jan. 5, his second since the death of Al-Arouri, Hezbollah chief Nasrallah said “the decision is now in the hands of the battlefield” and an adequate response will be “without limits.”

“The response is inevitably coming,” he said during the live-streamed speech. “We cannot remain silent on a violation of this magnitude because it means the whole of Lebanon would be exposed.”

However, analysts suspect Hezbollah would prefer to avoid a war with Israel, regardless of its sympathies with Hamas and the Palestinians suffering in Gaza, choosing instead to preserve its stockpile of weapons as deterrence against any potential Israeli attack on Iran.

“Hezbollah very much wants to maintain the current status quo and avert an all-out war with Israel,” Firas Maksad, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute and adjunct professor at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, told NPR on Jan. 7.

“The current status quo suits Hezbollah very well because they are reverting to asymmetric warfare, ‘grey zone’ warfare, some would say, where they can harass Israel across the border, show their support for Hamas and the Palestinians by forcing Israel to redeploy and refocus hundreds of thousands of troops away from Gaza to that northern border, but nonetheless stop short of an all-out war that might be in Israel’s favor.”

An image grab from Hezbollah's Al-Manar TV taken on January 5, 2024, shows the head of the Lebanese Shiite movement Hezbollah Hassan Nasrallah delivering a televised speech, with a picture of killed Hamas's deputy chief Saleh al-Aruri to his left. (AFP)

Israel is also widely seen as wanting to avoid opening an additional front in the war that might expose its cities to Hezbollah’s formidable arsenal of missiles.

However, there are those in the Israeli government who believe Hezbollah poses too great a threat to Israel’s national security to be left unchallenged forever, making conflict a distinct possibility once Hamas has been defeated in Gaza.

In an analysis published on Jan. 2, Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, said it was unlikely Israel would risk undermining its Gaza operation by going on the offensive against Hezbollah.

He added that although many in the Israeli establishment “may share a desire to knock out Hezbollah as a potent military threat, they are likely to avoid opening a second, northern front if there is any risk that this might impede their ability to ‘finish the job’ in Gaza.

“Widening the Gaza war into a regional one — even if limited to Lebanon — might spook the US and European governments into more active diplomacy, which could potentially constrain Israeli freedom of military action in Gaza and limit its options for the post-conflict phase there.”

Nevertheless, with a hostile entity on its doorstep, Israel might feel forced to take action against Hezbollah eventually.

“The current status quo, while it suits Hezbollah and Iran, as I mentioned, does not suit the Israelis,” Maksad told NPR.

“The Israelis have about 75,000, 80,000 citizens who’ve vacated the north for fear that Hezbollah, much more capable than Hamas, would do to them what Hamas did in southern Israel. And they’re not willing to come back unless that is settled.

“So Israel is demanding that Hezbollah pull its forces, at least its elite troops, away from that border, or else it’s threatening war.”

Even if all-out war between Israel and Hezbollah is avoided, Nasrallah’s posturing and the militia’s cross-border attacks alone have been enough to undermine and delegitimize the sovereignty of the Lebanese state.

For Lebanese citizens such as Saadi this means, in the absence of a functioning government, the continuation of the country’s political paralysis, institutional decline and economic misfortune.

“It is not ours anymore, it is Iran’s now,” Saadi said of his nation. “We haven’t tasted sovereignty since we were established, always being tossed from one power to the other, starting with the French and ending currently with Iran.

“Hope is futile here but I can’t help but to hope that Hezbollah will put Lebanon’s needs ahead of its master, Iran, and spare us a war we will not survive.”