LONDON: Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip has resulted in the damage and destruction of precious records and archives, placing the preservation of Palestinian heritage and identity in jeopardy, scholars have warned.

Keen to preserve items and documents pertaining to the history of Palestine, a digital platform, Palestine Nexus, launched in 2020, has redoubled its efforts to gather and protect treasures drawn from archives across the Middle East.

“With the number of stories of people that are being literally wiped off the face of the earth, this is like a tiny, tiny contribution, but it just feels like an obligation,” Zachary Foster, the founder and owner of Palestine Nexus, told Arab News.

“I believe in preserving Palestinian memory in history … and I’m proud to contribute to that.”

Documents reduced to ashes are scattered inside the archives department of the Gaza municipality building. (AFP/File)

Israel mounted its military campaign in Gaza in retaliation for the unprecedented Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel by the Palestinian militant group Hamas, which saw 1,200 people killed, most of them civilians, with 240 taken hostage.

In the months since the outbreak of fighting, more than 22,700 people have been killed in Gaza by Israel’s bombardment, according to the Hamas-run health ministry, while almost 2 million have been displaced.

Civilian infrastructure has been damaged or destroyed and only limited humanitarian aid has been permitted to enter the embattled enclave, leaving the population vulnerable to hunger and disease.

Amid the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe, it has been easy to overlook the harm the conflict has caused to cultural, educational and heritage sites and the historical artifacts held therein. This has seen the erasure of significant elements of Palestinian history and identity.

In late November, Gaza’s Central Archives, which contained thousands of historical documents dating back more than 150 years, was destroyed.

In an interview with Turkiye’s Anadolu news agency, Yahya Al-Sarraj, head of Gaza’s municipality, described the destruction of the archives as a deliberate attempt to “erase a large part of our Palestinian memory.”

Other sites of cultural significance damaged or destroyed in recent weeks include the Mavi Marmara Martyrs Memorial in Gaza Port, the memorial of the late journalist Shireen Abu Akleh in the West Bank’s Jenin refugee camp, and the memorial of the late President Yasser Arafat in Tulkarm, also in the West Bank.

Gaza’s largest public library has also been destroyed. In response, municipal authorities called on UNESCO to “intervene and protect cultural centers and condemn the occupation’s targeting of these humanitarian facilities protected under international humanitarian law.”

Israel insists its armed forces are only targeting Hamas fighters, commanders, weapons caches and tunnel networks — not civilians and civilian infrastructure or sites of cultural, religious or historical significance.

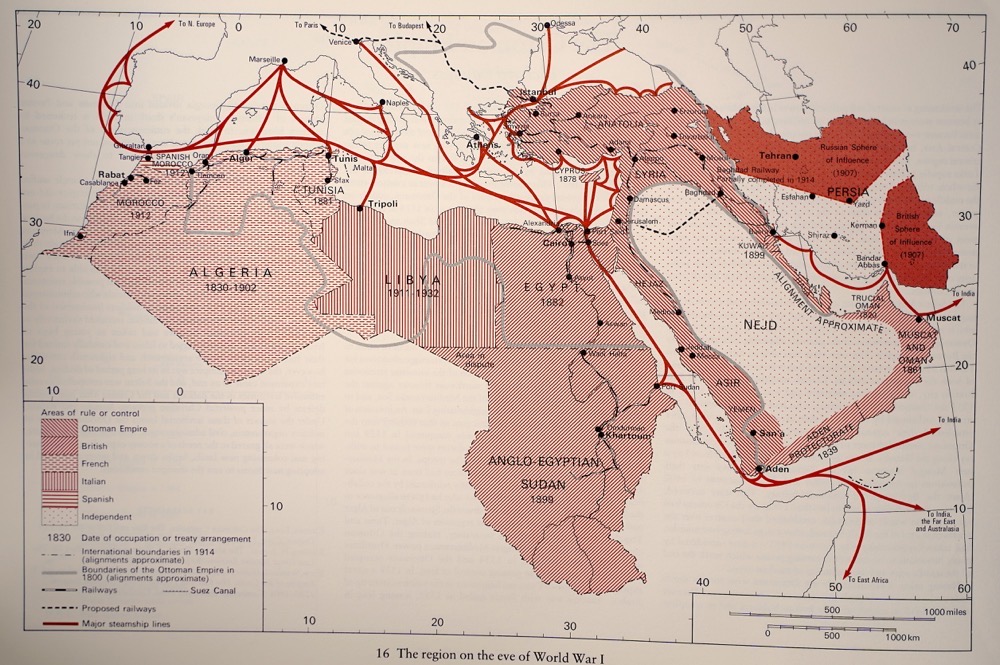

Even before the conflict in Gaza began, Omar Suleiman, an American-Muslim scholar, had warned of a systematic erasure of the concept of Palestine — from maps, academic works, and the public discourse itself.

“It’s not just the Palestinian people or the name of the country that’s disappearing, but the word Palestine itself,” Suleiman said in a recent op-ed for Al Jazeera. “Palestine is being deliberately erased from our consciousness and discourse, during war and even in peace.”

As the conflict persists in Gaza, scholars will increasingly have to rely on digital archives to access primary source materials because hard copies are damaged or destroyed. As a result, platforms such as Palestine Nexus will become more vital than ever.

“I became interested in Palestinian history and identity because I was raised with all of these myths about how there was no such thing as Palestinian people,” said Foster, a US citizen of Jewish heritage. “I wanted to know if all those stories that I heard were true or not.”

A worker walks toward the archives department of the Gaza municipality building in Gaza City during Israel-Hamas war. (AFP/File)

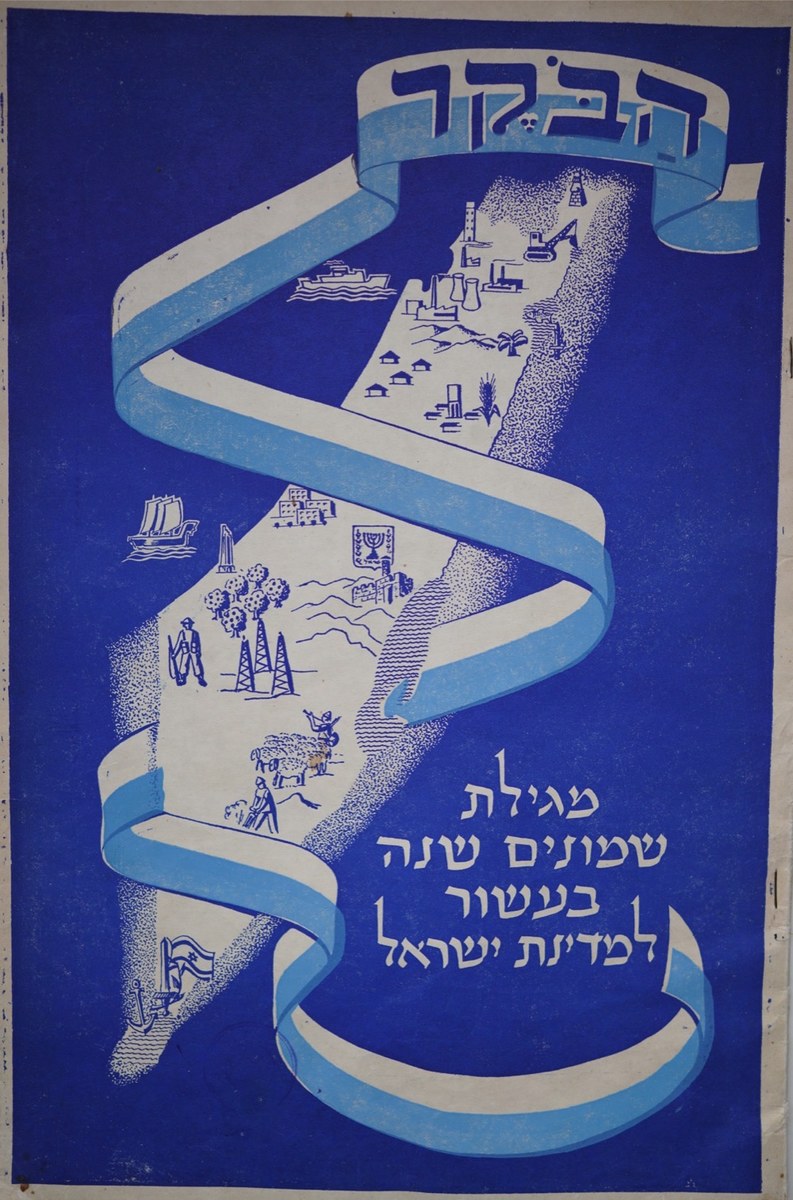

Foster’s academic quest to discover the origins of Palestinian identity led him to collect a mesmerizing array of maps of Palestine from the 19th century. These beautifully crafted and incredibly rare documents became the cornerstone of Palestine Nexus.

“It was my argument that maps of Palestine played a key role in explaining why it is that people began to identify as Palestinian and so I tried to find every map of Palestine from the 19th century that I can find,” he said.

“And at some point, I realized I had a lot more than just maps.”

As Foster delved deeper, his project evolved from a personal interest in Palestinian history and identity into a mission to make rare historical documents accessible to a global audience. He expanded his collection beyond maps to encompass digital copies of diaries, manuscripts, newspapers, and archival materials.

Soon, Palestine Nexus had transformed into a comprehensive repository, not limited to Palestine but extending its reach to the broader Middle East.

The curated repository, now boasting more than 40,000 objects, includes identification papers, official records, letters, diaries, manuscripts, maps, photographs, films, and audio recordings, and even the first dual-language geography book chronicling the history of Palestine in Greek and Arabic, published in 1904.

Additionally, it houses the first “History of Gaza” penned and published in Arabic in the 20th century by ‘Arif Al-‘Arif and hundreds of documents covering the periods of Ottoman and British rule.

It also features the “Palestinian Arab Index, 1946,” a book that constitutes one of the most comprehensive and contemporary indices of books published in Palestine or by Palestinian Arabs in the first half of the 20th century.

After years of treasure hunting across the region, which took him to Egypt, Turkiye, and Palestine, Foster’s visit to Gaza unearthed a unique collection spanning the social, political, and economic history of Palestine from the 1910s to the 1980s.

Saleem Elrayes, an antiques dealer from Gaza City, had compiled a collection that chronicled the social history of Gaza during the 1948 war, documents related to his family business importing coal from Sudan in the 1910s, and a diverse array of maps depicting events in the Gulf, including Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

The chronicle, named the Gaza Collection, was partially acquired by Foster, who transported it to the US and digitized the materials so that it could be accessed by scholars for free on Palestine Nexus.

“I visited Gaza twice,” said Foster. “The first time I bought maybe 400 (to) 500 documents, and the second time I went back, I bought another 300 (to) 400 documents.” However, his meeting with Elrayes unlocked a gold mine of previously unseen material.

Documents reduced to ashes are scattered inside the archives department of the Gaza municipality building. (AFP/File)

“He has five, 10 times as many documents as I purchased,” said Foster, who is mesmerized by Gaza’s unexpected archival richness, considering its challenging circumstances over the past 16 years of Hamas rule and Israeli embargo.

However, the chances of a return visit to Gaza in the near future appear slim. Elrayes, the custodian of this unique collection, was forced to abandon his home in Gaza City following heavy Israeli bombardment.

It is not yet known whether his antiques shop is still standing or has been “blown to pieces.” The uncertainty surrounding the fate of this physical archive lends even greater significance to digital preservation efforts.

Reflecting on his platform’s importance, Foster underscored how the documents in the Palestine Nexus archive are a testament to the rich history, culture, and memory of the Palestinian people, countering a narrative that often seeks to erase or downplay their identity.

“The Gaza municipal archives were destroyed. Saleem’s archive may well have been destroyed. The entire 60 (to) 75 percent of the housing stock is destroyed. Everything has been destroyed. And yet, people’s history exists and it will be preserved,” said Foster.

With nearly 200 access requests and more than 500 expressions of interest, Foster says he is curious to know who is accessing the collection, mindful of the growing impact of — and public engagement with — the project.

He said the interest in this “obscure collection” is a remarkable achievement, signifying a genuine concern for the fate of these historical documents and the stories that they contain.

Looking ahead, Foster says he hopes Palestine Nexus will inspire other archival initiatives, fostering a culture of open access to historical documents, crucial for Palestinians facing barriers to physical access and ensuring preservation in the face of potential destruction.