LONDON: From a deadly earthquake in the country’s northwest and protests in its far south to a return to the Arab fold after more than a decade out in the cold, Syria has witnessed several major events and changes in the past year.

These developments have taken place against the backdrop of a deepening economic crisis, humanitarian challenges, a resurgent Daesh insurgency, and violence associated with Syria’s unresolved civil war.

Suweida protests

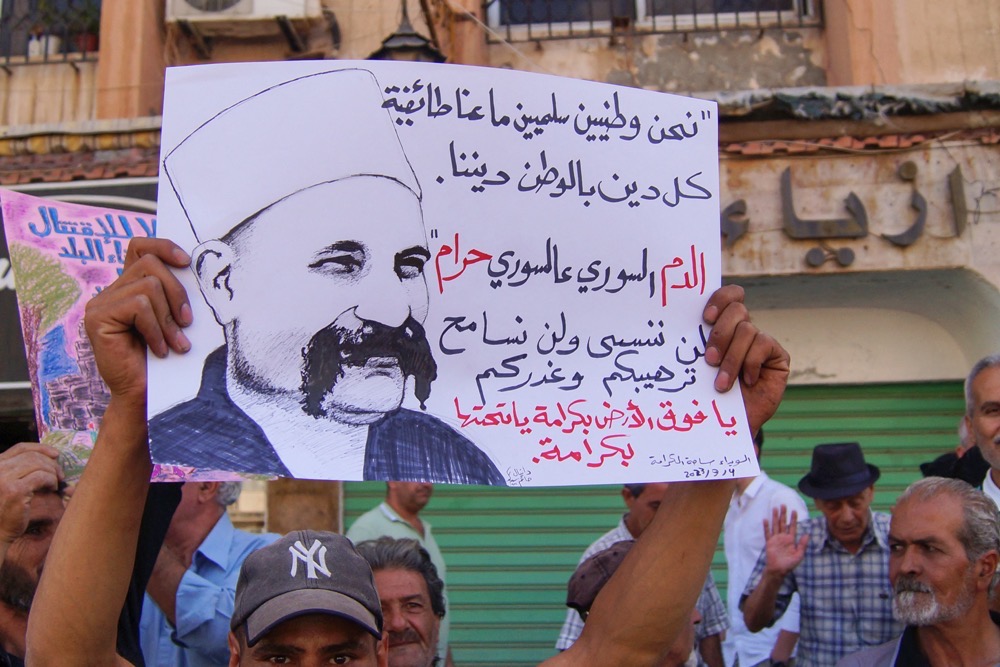

Anti-regime protests erupted in August in southern Syria, mainly in the governorate of Suweida, in the wake of government decisions that have contributed to a mounting cost-of-living crisis.

Echoing Deraa’s demonstrations of 2011, which ignited a country-wide civil war, the protesters in Suweida have called for the overthrow of the regime of Bashar Assad — the first and most determined challenge to his rule in years.

Protests have also occurred in other parts of Syria, including Deraa, Idlib, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor and Aleppo.

Anti-regime protests erupted in August in southern Syria, mainly in the governorate of Suweida. (AFP)

In August, the Assad government reduced fuel subsidies and raised gasoline prices by nearly 250 percent. And although the government doubled public sector wages and pensions, the average Syrian breadwinner is still struggling to make ends meet amid rising prices.

Years of conflict and Western-imposed sanctions have left Syria’s economy in tatters. Hyperinflation, fuel shortages, prolonged power cuts, and devastated infrastructure are just some of the challenges people in the war-torn country face every day.

The UN World Food Programme estimated in May that around 12.1 million people in Syria — representing more than half of the population — are food insecure. As such, Syria was already on its knees at the beginning of 2023.

Worse was still to come, however, when the north of the country was struck by two massive earthquakes on Feb. 6, impacting some 8.8 million people and shattering much of what remained of its infrastructure.

The earthquakes

In the early hours of Feb. 6, people across southern Turkiye and northern Syria were shaken from their beds by a magnitude 7.8 earthquake, the largest to hit the region since the 1939 Erzincan temblor. Nine hours later, a second earthquake of magnitude 7.5 shook the region.

In Syria, the twin quakes killed more than 8,000 people, destroyed some 1,900 buildings, caused around $5.1 billion in direct physical damage, and displaced thousands of people, many of whom had already been displaced multiple times by the conflict.

Although the death toll and physical damage were far more extreme in Turkiye, where the strongest tremors were felt, Syria’s political isolation and years of impoverishment intensified the suffering of its people.

A resident of Jindayris rests among rubble after a deadly earthquake that hit parts of Syria. (AFP)

Shortly after the earthquakes, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, estimated that approximately 5.37 million people in Syria were in need of shelter assistance.

Three days after the disaster struck, the US Treasury announced a 180-day exemption from sanctions on “all transactions related to earthquake relief efforts” sent to Syria by overseas donors.

Several Arab states responded to the disaster by sending aid convoys even before the sanctions were eased, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iraq, Algeria, and Bahrain.

However, many Syrians and local nongovernmental organizations complained that they did not receive anything like the same level of international assistance provided to Turkiye.

Indeed, rescue teams in opposition-controlled northwest Syria had to claw their way to people trapped under rubble without the aid of machinery due to fuel and equipment shortages.

Return to the Arab fold

In part, it was because of the Arab world’s response to the earthquakes that a dialogue between regional governments and the Assad regime became possible.

After years of isolation and dependence for survival on Russia, Iran and the Iranian regime’s regional proxies, Assad was finally brought back into the Arab fold on May 7, when the Arab League gave him a warm welcome at that month’s summit in Jeddah.

Syrian President Bashar Assad attends the Arab League’s summit in Jeddah. (SPA)

Following its crackdown on anti-government protests in 2011, which sparked the civil war, the Syrian regime was made an international pariah, ostracized by many Arab states, and suspended from the Arab League.

While Assad’s return to the Arab fold signaled the end of the regime’s isolation, this was conditional on his commitment to curbing drug trafficking into neighboring countries and upon the repatriation of refugees.

Prior to the Jeddah summit, a meeting of Arab foreign ministers, including Syria’s Faisal Mekdad, in the Jordanian capital Amman saw Damascus agree to tackle drug smuggling on its shared borders with Jordan and Iraq.

Captagon crackdown

On May 8, a day after Damascus was reinstated into the Arab League, Jordanian warplanes targeted one of the region’s most prominent drug traffickers, Marai Al-Ramthan, in Syria’s southern province of Deraa, killing him and his family.

Since the start of the Syrian civil war, Jordan has been a major transit point for the trade in Captagon, a highly addictive amphetamine, which has enjoyed a large market in wealthy Gulf countries.

The Syrian government previously denied accusations it was involved in the trade and manufacture of Captagon. (AFP)

During the meeting of Arab foreign ministers that took place in Amman on May 1, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi said his country would not stand idle if drug smuggling continued from Syria.

Since 2014, Amman has launched multiple raids against drug traffickers inside Syria. The Jordanian military said in February 2022 it had killed 30 such criminals since the start of the year.

The Syrian government previously denied accusations it was involved in the trade and manufacture of Captagon, despite a body of evidence indicating people close to the Assad regime were involved in the industry.

Israeli airstrikes

In October, Israel carried out airstrikes against civilian airports in the capital Damascus and the northern city of Aleppo, knocking them both out of service.

Although Israel has repeatedly struck targets inside Syria in recent years, claiming it was bombing Iran-linked targets, these particular raids came in the wake of the deadly Hamas attack on southern Israel.

On Oct. 7, the Palestinian militant group, which has controlled the Gaza Strip since 2007, carried out a surprise attack on Israel, killing at least 1,200 people, most of them civilians, and taking around 240 hostages.

Israel responded to the unprecedented attack by launching a massive bombing campaign and ground operation against Gaza.

As of Dec. 20, at least 20,000 Palestinians, 70 percent of whom are women and children, have been killed according to Gaza’s Hamas-run health ministry.

Strikes on targets inside Syria are part of a shadow war between Israel and Iran’s proxies. (AFP)

Israeli fighter jets extended their strikes to include targets in both Syria and Lebanon, which have both played host to militias backed by Iran and sympathetic to Hamas.

Aerial attacks on Syria since Oct. 7 have reportedly hit both military and civilian sites, including the Syrian army air defense base and a radar station in Tel Qulaib and Tel Maseeh in Suweida province.

Strikes on targets inside Syria are part of a shadow war between Israel and Iran’s proxies in the region, which have long been accused of transferring Iranian weaponry, including missiles and drones, to armed groups in Lebanon and elsewhere.

If hostilities between Israel and these groups escalate in the coming days, there are fears that Arab countries like Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen could find themselves dragged into a devastating regional conflict.