TURKMENBASHI: On the Caspian Sea coast in Turkmenistan, Batyr Yusupov can no longer ferry his passengers between two ports. There is not enough water.

“I used to go between Turkmenbashi and Hazar,” the 36-year-old ferry worker said of the ports separated by a small gulf on Turkmenistan’s coast.

“But we haven’t been able to go there for a year due to the serious shrinking of the Caspian,” he said.

In at least one seaside city, local bathers have noted the waters receding by hundreds of meters.

But it is not just about ferry routes or having to walk further for a proper swim: the changes hit the heart of Turkmenistan’s struggling economy.

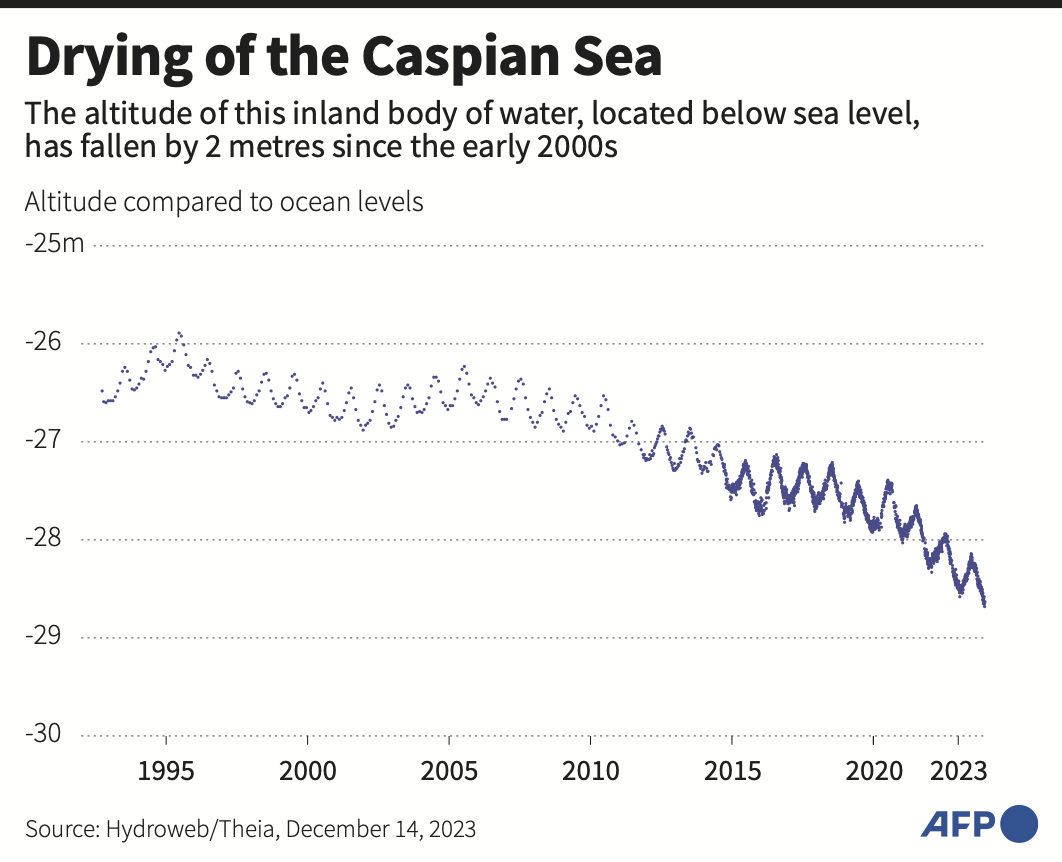

And year after year, the water levels are falling.

It is still not entirely clear why that is happening, but scientists say it is down to naturally occurring processes exacerbated by climate change.

One 2021 study projected that by 2100, water levels in the Caspian Sea could drop by another 8 to 30 meters (26 to 98 feet).

The Caspian Sea, an inland body of water, is flanked by the Caucasus region to the west and Central Asia to the east.

Turkmenistan, a former Soviet republic, is one of five countries on the Caspian Sea together with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Iran and Russia.

And they are all, to some extent or another, affected by the changes.

South of Turkmenbashi, in the seaside town of Hazar, satellite images show the shore has receded around 800 meters (half a mile) on both sides.

That has turned the town, which sits at the end of a peninsula, into an island.

Instead of sailing between Hazar and the main port of Turkmenbashi, Yusupov now takes passengers to Gyzylsuw — between the two — which is more accessible by boat.

But even there, the situation is not much better.

“A new pier is being built because the old one is no longer deep enough,” said one local resident, 40-year-old Aisha.

Dozens of rusty boats line the shore in Gyzylsuw.

Aisha’s house has stilts protecting it from the sea, which now seem superfluous.

“Even during storms, the water doesn’t reach the house,” she said.

In Turkmenbashi itself, Turkmenistan’s largest coastal city, the changing shoreline is evident to swimmers.

“Last summer, the water was up to my shoulders, then around my waist,” said one regular, 35-year-old Lyudmila Yesenova.

“This year, it’s below my knees.”

The receding waters threaten the maritime infrastructure of Turkmenbashi, a major Central Asia port crucial for trade between Europe and Asia.

And on the opposite coast of the Caspian lies Baku, the capital of oil-rich Azerbaijan.

Turkmen Foreign Minister Rashid Meredov sounded the alarm in a recent speech.

“At present, the sea level is close to the minimum values for the entire time of instrumental observations,” he said in August.

“In the last 25 years, it has decreased by almost two meters,” which meant that the retreat of the sea had become particularly noticeable in recent years, he added.

“The sea has moved hundreds of meters away from its former shores,” he said. “In the north of the Caspian these figures are even higher.”

Neighbouring Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s largest country, has echoed some of Turkmenistan’s concerns.

But after years of disputes over the control of huge hydrocarbon reserves in the region, the collaboration Meredov has called for is only in its earliest stages.

Turkmen scientist Nazar Muradov attributes the changing sea levels to “tectonic movements and seismic phenomena, which change the seabed.”

He said the sea level had previously fallen in the 1930s and the 1980s before rising again. But the changing climate also had to be factored into this latest phenomenon, he added.

“The sea level also depends on the flow of rivers — whose levels are diminishing — as well as low levels of precipitation and intense evaporation.”

Kazakhstan also depends on the sea for its oil and gas industry.

The drop in water levels, coupled with a rise in temperatures, has also hit marine life in the Caspian, including seals.

In a sign he is taking the situation seriously, Kazakh leader Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has announced he had taken the decline in the seal population under his “personal control.”

He also said Kazakhstan would create a research institute for the study of the Caspian.