KARACHI: Nazia Saif, an Afghan refugee residing in a small apartment in Karachi’s busy Al-Asif Square area, is concerned with what the future holds for her after police arrested her husband, a daily wager, last Monday on charges of being an illegal Afghan immigrant. With her husband gone and a family to feed, Saif wonders who will put food on the table for them.

Pakistan launched a crackdown against illegal immigrants in the country on Saturday, Sept. 9. Police rounded up hundreds of Afghan citizens in Pakistan’s financial hub Karachi, accusing them of being illegal immigrants in the country. Last Friday, Caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar said Pakistan would repatriate all illegal Afghan immigrants to curb smuggling of goods and foreign currency.

Pakistan first opened its borders to Afghan refugees in the 1980s after the beginning of a US-sponsored and Pakistan-backed ‘Afghan jihad’ to counter the so-called expansionist designs of the former Soviet Union, becoming the largest refugee-hosting country in the world. As per the UN, over 4.4 million Afghan refugees have returned to their homeland since 2002 under a UNHCR-assisted voluntary repatriation program, but around 1.4 million still live in refugee camps, villages and urban centers across Pakistan.

“My husband used to work hard to feed his children. Now, when they arrested him, what will we do?” Saif, 28, told Arab News, adding that Saif-Ud-Din possessed Proof of Registration (PoR) Card, which entitles Afghan immigrants to legally stay in Pakistan.

“This is not how the law works, it has some rules.”

Nazia Saif, 28, an Afghan refugee residing in the Al-Asif Square neighborhood, gestures with her children during an interview with Arab News in Karachi on September 20, 2023. (AN Photo)

Saif-Ud-Din, 32, was selling fries at a roadside stall when police arrested him on Sept.11. Afghan Consul General in Karachi, Syed Abdul Jabbar, said over 900 individuals have been arrested since Sept. 9 when the crackdown began. Two hundred individuals have since then been released, he said.

“More than 900 have been arrested and the crackdown still goes on and the police continues to harass Afghan refugees with legal documents,” Jabbar told Arab News.

Arab News reached out to the Sindh Chief Minister’s office, the Inspector-General of Police and Karachi police chief to comment on the allegations but did not receive a response. Pakistani police authorities have in the past rejected allegations they harass Afghan immigrants legally entitled to stay in Pakistan.

Karachi police spokesperson Rehan Khan confirmed to Independent Urdu on Tuesday police had initiated a crackdown against illegal Afghan immigrants since Sept. 9. He said police had arrested a total of 545 illegal Afghan immigrants from Sept. 9-14.

Hajji Abdullah, the head of the Afghan refugees in Sindh, said he had data that indicated that 1,200 people had been transferred to jails since Sept. 9 while 3,800 secured their release after allegedly paying bribes to police.

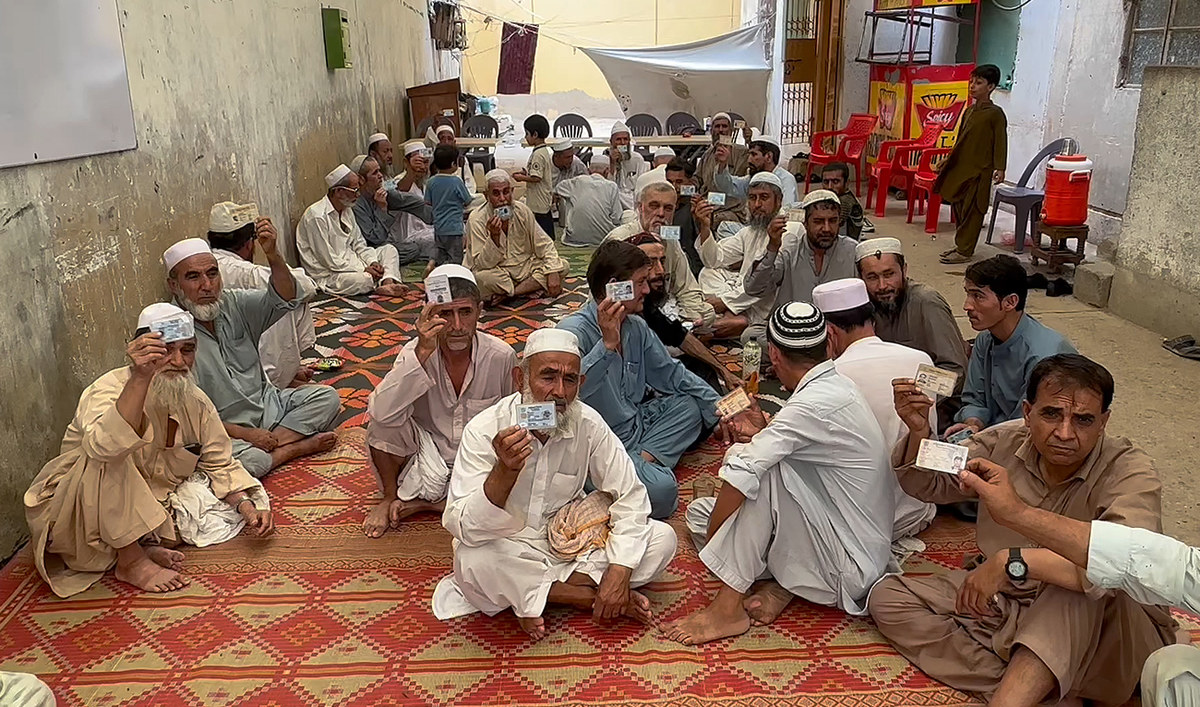

A group of Afghan refugees, residing in the Al-Asif Square neighborhood, carry Proof of Registration cards on camera during an interview with Arab News in Karachi on September 20, 2023. (AN Photo)

Hailing from Kunduz in Afghanistan, most of Saif’s family members, including her brother Ihsan Khan, were born in Pakistan. Khan is also among the Afghan refugees who were arrested in the crackdown.

“He [Khan] was arrested just a day earlier as well, and they took his Rs1,000 ($3.39) wage and destroyed the photocopy of his card,” Saif lamented, as her mother chimed in, saying that the arrests had devastated the family.

“Who will take care of the household needs? Who will arrange the food, as my son is in jail,” she asked.

In the wake of these arrests, the family prohibited Salahuddin, Saif-ud-Din’s younger brother, from venturing outside. Salahuddin has been confined to his home for the past nine years.

“When I went to the market today to buy fruit, a policeman took Rs7,000 [$23.75] from me,” Salahuddin, 20, told Arab News. “He threatened me, saying that if I didn’t give him the money, he would take me to Gulshan-e-Maymar’s jungle and kill me in an encounter.”

Naqeebullah Khan, another refugee, said Afghans felt compelled to either stay indoors or, if they must go out, take their young children along as a form of protection against police.

“When we go out, we have to make our little child sit on the motorcycle, as if he is our passport and ID card,” he said. “We do have the cards, but they don’t work in front of the police. We go out on roads like thieves.”

This dire situation, as described by Abdullah, has restrained Afghans to their homes, with people unable to conduct business or earn daily wages to support their families.

“For the last 12 days, Afghan homes have turned into prisons,” Abdullah said.