IRBIL, Iraqi Kurdistan: Shortly after midnight on Aug. 3, 2014, heavily armed Daesh extremists swept into the Yazidi homeland of Sinjar in northwestern Iraq, rounding up the civilian population to slaughter them or take them into captivity.

Daesh deliberately targeted the Yazidi community, one of Iraq’s oldest ethnoreligious minorities, because it considered them apostates for their religious traditions. Nine years later, the survivors are still coming to terms with what happened.

“I remember my parents frantically waking me and my siblings up at around 2 a.m.,” Barzan H., 23, told Arab News in Irbil, the capital of the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region of Iraq, where he now resides along with thousands of other displaced Yazidis.

“I peeked out of the windows and saw black trucks and jeeps coming in from the distance. The men who were older and able took up arms, with the rifles they had at home and anything else they could get their hands on to protect us.”

Barzan was only 14 years old when Daesh attacked his hometown. As the extremists advanced, he and his neighbors grabbed whatever they could carry and fled their homes. About 400,000 were displaced. Few would return.

“I recall hiding in the mountains until 8 a.m. It was hot. We were thirsty and physically exhausted from the fear and the fleeing,” said Barzan.

However, the militants soon caught up with them and encircled the area.

Yazidi survivors of Daesh atrocities in 2014 have spoken about their ongoing struggle to find justice and cope with grief and loss. (AFP/File Photo)

“They were on to us,” he added. “They put us in their trucks and hauled us off to a deserted building. They split the women and female children from us minors who were male.”

Those who had been captured were taken to a school building, where the women and children were separated from husbands and brothers. Those men and the elderly who refused to convert to Islam were massacred.

As for the women and children, an estimated 7,000 were bundled onto trucks and forcibly relocated to Syria and other parts of Iraq, where many were trafficked into domestic servitude or sexual slavery.

Boys and younger men were taken away for training and brainwashing to become “cubs of the caliphate,” forced to fight alongside the militants.

“My friends and I were taken to Tel Afar, then to Mosul,” said Barzan. “They told us to forget about our religion, that we were to convert to Islam and start military training.”

His training took place in Deir Ezzor, Syria, and then he was deployed to the front line in Iraq’s Mosul, where some of the heaviest combat against Iraqi and coalition forces would later take place.

“I had some friends for whom Daesh’s brainwashing was effective, and they were the ones who turned into suicide bombers,” Barzan said.

“I saw Daesh soldiers killing sons in front of their mothers, I saw them taking away prepubescent girls from their mothers’ arms to rape them.”

As Daesh’s self-proclaimed caliphate began to crumble, the militants were gradually pushed back to their last holdout of Baghouz in Deir Ezzor. In early 2019, as the Syrian Democratic Forces and their coalition partners closed in, Barzan’s father contacted a smuggler to rescue his son.

Under heavy bombardment, Barzan was able to desert from his regiment and escape from Baghouz. It took him five days to cross no man’s land and reach safety.

Although he was eventually reunited with his surviving family, the fate of his sister and two brothers remains unknown. His family, like thousands of others, has not returned to Sinjar.

Thousands of Yazidis trapped in the Sinjar mountains as they tried to escape from Daesh forces rescued by Kurdish Peshmerga forces and Peoples Protection Unit (YPG) in Mosul, Iraq in 2014. (Anadolu Agency/Getty Images/File Photo)

“There is nothing to return to,” said Barzan. “They (Daesh) broke Sinjar down. Too many lives lost, too much blood.”

In March 2021, Iraq’s then-president Barham Salih ratified the Yazidi Survivors’ Bill, which mandated reparations and material compensation for Yazidis and other minority groups that had been persecuted by Daesh. The Iraqi government also said it would invest in Sinjar’s reconstruction.

However, the bill and the promised reconstruction have yet to be properly implemented and the majority of the Yazidis remain displaced across the Kurdistan region, mostly concentrated around the city of Duhok in makeshift camps.

“The Muslim community had their houses rebuilt,” Barzan said. “Our village is still rubble and we are tired of knocking on organizations’ doors and not being compensated. The Iraqi government doesn’t really care for us.”

Yazidi women and girls suffered the worst indignities at the hands of Daesh, with many of them sold into sexual slavery and forced to bear the children of their captors.

“I was about 15 years old. That night plays in my head almost like a movie. Some parts I wish to forget,” Siham Suleiman Hussein, a 23-year-old Yazidi who now lives in the Khanke Camp near Duhok, told Arab News as she recalled Daesh’s arrival in Sinjar.

“The militants found us hiding in the mountains. They put us in their trucks and drove us into Iraq. They kept us at Galaxy Hall, a wedding venue. The younger girls were separated from their mothers. Elderly women were sent to Mosul.”

It was there that Hussein was put up for sale. She was first bought by a Tunisian Daesh fighter who “thankfully died a few days after my purchase,” she said. “The few days I spent with him were brutal.”

She was later bought by a Libyan militant.

FASTFACTS

* Daesh attacked the Yazidi homeland of Sinjar in northwestern Iraq on Aug. 3, 2014.

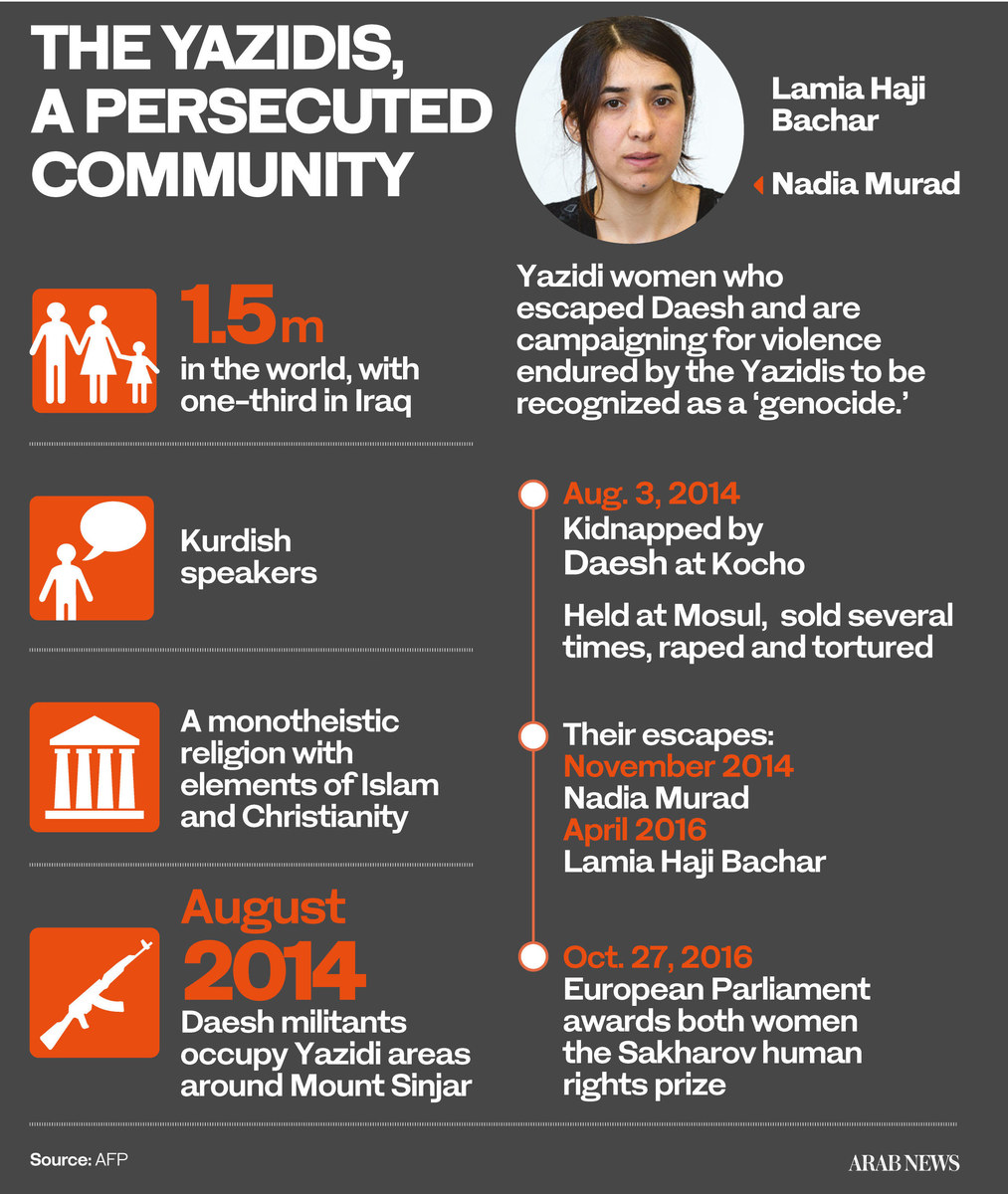

* Nearly 3,000 women and children are still missing 9 years later, says survivor Nadia Murad.

* The UK formally recognized Daesh’s persecution of the Yazidis as genocide on Aug. 1, 2023.

“Sometimes my memory is vivid, other times I feel like there are blank spaces in there,” she said. “I think my brain is actively and purposefully blanking things out to protect me.

“I resisted all throughout my captivity. I never lost hope that I would be rescued.”

Hussein remained with the Libyan man for a few months before he “gifted” her to a Syrian friend.

“I was constantly beaten and starved,” she said. “They broke bones in my body.”

She attempted to escape several times, without success. Each time she was brought back, her punishments were increasingly severe.

After one escape bid, she said the Syrian militant “brought a knife, held it against my neck and whispered in my ear that he would slit my throat if I ever tried to escape again. But I told him I really had no fear of death, especially after my community was massacred.”

Hussein was eventually rescued thanks to her uncle, Abdullah, who sent an Arab, posing as a Daesh militant interested in purchasing her.

“When the purchase was taking place, I was screaming to be left alone,” she said. “I was yelling at them, telling them they were monsters, that people shouldn’t be bought and sold.”

The man her uncle had sent whispered that he was there to save her. She was later reunited with what remained of her family.

The Yazidis — whose pre-Islamic religion made them the target of Daesh extremists — were subjected to massacres, forced marriages and sex slavery during the jihadists’ 2014-15 rule in the northern Iraq province of Sinjar, the Yazidis’ traditional home. (AFP/File Photo)

“I lost my father, my grandfather and my brothers,” said Hussein. “We don’t know if they are dead or alive.

“Life is so hard without them. We live in this camp, women on our own. Some NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) used to come over to offer us support but the aid has now dwindled. I also used to go to therapy but I have now stopped. I feel like healing should be done on one’s own.”

Reflecting on the life that was so cruelly taken from her, Hussein said she can never forgive the militants who kidnapped her and destroyed her home and family.

“I miss my old life,” she said. “We were a happy family, we had a farm and so many animals. We were innocents and we had our innocence stolen. I wish those terrorists twice the suffering they imposed on us.”

In the run-up to the ninth anniversary of the attack on Sinjar, the UK government formally recognized the acts committed against the Yazidi community as genocide.

Tariq Mahmood Ahmad, Britain’s minister of state for the Middle East, said last week that the Yazidi population “suffered immensely at the hands of Daesh nine years ago and the repercussions are still felt to this day. Justice and accountability are key for those whose lives have been devastated.”

He added: “Today, we have made the historic acknowledgment that acts of genocide were committed against the Yazidi people. This determination only strengthens our commitment to ensuring that they receive the compensation owed to them and can access meaningful justice.

“The UK will continue to play a leading role in eradicating Daesh, including through rebuilding communities affected by its terrorism and leading global efforts against its poisonous propaganda.”

Yazidi survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Nadia Murad welcomed the announcement.

“Today, the British government formally acknowledges the Daesh attacks on my Yazidi community in 2014 was genocide,” she said in a message posted on Twitter.

“Thousands died, thousands more were enslaved and so many of us are displaced and traumatized. I hope this step by Tariq Mahmood Ahmad and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office brings us closer to justice.”

The UK has officially recognized five genocides: the Holocaust, Rwanda, Srebrenica, Cambodia and now the Yazidis.

Masrour Barzani, prime minister of the Kurdistan Region, said on Twitter that he “welcomes the UK’s decision.”

He added: “Our Yazidi brothers and sisters have prevailed and remain strong. We stand by our proud people as they heal and rebuild.”

Barzani’s government continues to call on federal authorities in Baghdad to deliver on their promise to reconstruct Sinjar so that the Yazidi community can return to its homeland.

Meanwhile, survivor Barzan earns a living training horses, an occupation that he says provides a measure of catharsis. However, the emotional wounds inflicted by the trauma of his abduction, the loss of his family and his years fighting under the command of his kidnappers remain raw.

“All I can say is, Alhamdulillah (praise be to God), life goes on,” he said. “Everyone’s fate is written and sealed.

“My family tree’s branches have been cut and I’ll never forgive those monsters. The battles are over but we continue with a trail of trauma.”