LONDON: More than 12 years into Syria’s devastating civil war, the country’s art sector continues to captivate audiences across the globe, thanks to the determination and talent of its creatives.

Internet access has been a crucial lifeline for many artists inside the sanctioned country, enabling them to participate in international fairs, sell their works abroad, and draw inspiration from global events.

“War and sanctions, which stunted the tourism sector, have isolated Syrian artists,” said artist Lina Malki, who has recently moved to the Egyptian capital Cairo. “But access to the internet and social media has been a bridge to the outside world, opening doors for us to partake in exhibitions abroad and fuel our imaginations.”

Lina Malki recently moved to the Egyptian capital Cairo. (Supplied)

Malki herself had her work exhibited in Canada while she was still in Syria.

The thought-provoking work of Damascus-based artist Mohammad Olabi — who told Arab News that the war in Syria has forced artists to develop greater resilience and embrace innovative approaches — has also garnered a following that transcends Syria’s borders. His paintings have been sold in the US, Paris and Berlin, among others.

Abir Arafeh’s masterpieces, meanwhile, have seen her gain a following in China while she continues to live in Damascus.

Abir Arafeh’s masterpieces have seen her gain a following in China while she continues to live in Damascus. (Supplied)

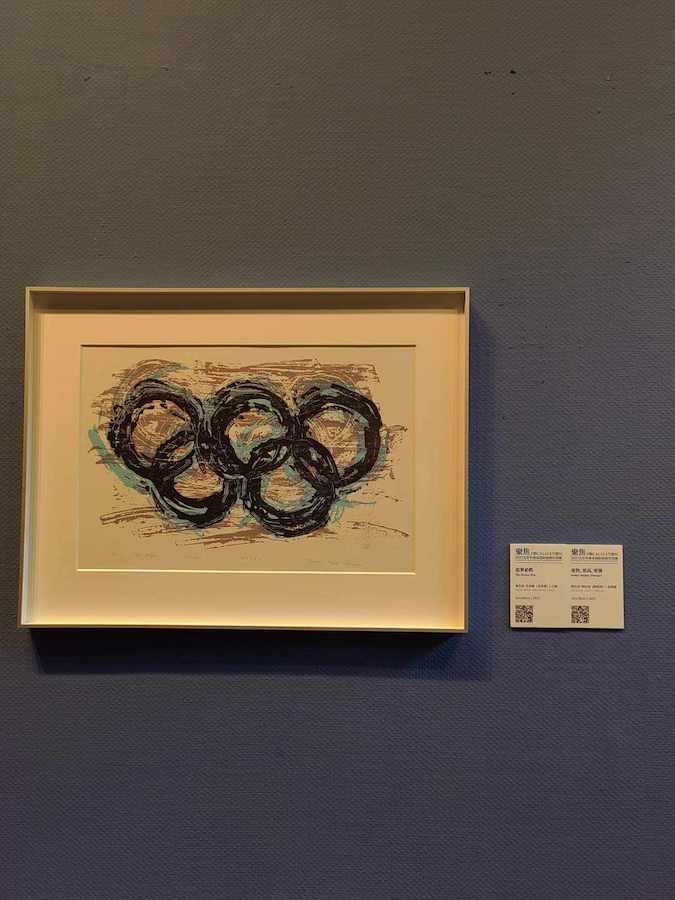

“I was one of 50 international artists invited to complete a printed artwork for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics International Printmaking Exchange Exhibition,” she told Arab News, adding that she also participated in the 7th China Guanlan International Print Biennial. Some of her work was also exhibited in London in 2020 and 2021.

The exquisite, meticulously tailored creations of Homs-based calligrapher, painter and fashion designer Dawlat Khaleel have traveled across Europe to be proudly worn by Arab women in France, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Germany, Austria, Denmark and Sweden.

Khaleel told Arab News her work was inspired by Syria, especially the details of her hometown.

“My work resembles me,” she said. “And it resembles my country. Most of my creations are of an Oriental nature. My goal is to fashion contemporary designs that have a classic as well as an Oriental essence, incorporating the beautiful art of Arabic calligraphy.”

Ahmad Idris used social media to start the non-profit community Make It Art to support local artists. (Supplied)

Ahmad Idris, who resides in Damascus, used social media to start the non-profit community Make It Art to support local artists. He told Arab News that, in 2017, he realized the need for a body to support young emerging artists, to document art exhibitions held across Syria, and to promote the country’s art scene in general.

Idris, who has been in the field for over a decade, and 22 other artists launched Make It Art that same year and it quickly evolved into a haven for artists where they would share their work and exchange knowledge.

However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, Idris has run Make It Art solo. The community has seen a severe decline in activity with people’s priorities shifting due to the economic collapse, he said.

The Claw, Mohammad Olabi, 2017. (Supplied)

That collapse, along with the stifling impact of US sanctions, has meant that even the acquisition of materials has become a major challenge for many Syrian artists. But Malki — who spent more than a decade teaching fine art at Damascus University, the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts, the Bulgarian Cultural Center, and Stage Art Center — stressed the unwavering determination of her peers and students in their pursuit of art.

She said that even though the country’s recession has taken a huge toll on Syria’s artists, “passion produces a need for self-expression.”

She continued: “So, when there was a shortage of materials, such as oil colors and sculpting clay, many resorted to alternatives like mud, collages, wood, and even coffee.”

Dawlat with her latest unfinished painting, wearing her own design. (Supplied)

Olabi noted that a career in art does not necessarily provide financial stability no matter where you are in the world. That is why, like Malki and many of his peers, he turned to teaching (“It keeps me connected to my passion,” he said). But he has no intention of stopping creating his own work.

“Art has become an essential need — vital for my survival,” he said. “It is a language through which I can communicate this phase's unique emotions and experiences.”

Idris currently runs his own studio, where he stages drawing and painting classes through which he hopes to invigorate Syria’s arts sector.

Despite their persistence, however, many of Syria’s artists are pessimistic about the sector’s future.

“I do not contemplate the artwork’s fate,” said Malki. “My passion for art is my sanctuary from the ugly reality. After the COVID pandemic, the (Syrian) currency collapsed drastically. Things became very difficult, and I was struggling to make ends meet. I had to move to Egypt, and now I’m working in graphic design alongside teaching arts in a private institute.”

For Khaleel, it is important that her “creations are born in Homs — from the heart of destruction and darkness,” she said.

“Not once have I thought about leaving (the country) or starting a business elsewhere because I want my work to be created in Homs and to travel the world from Homs,” she continued. “My city deserves that I never leave.”