LONDON: From the beginning of the protracted conflict pitting the regime against its opponents, Syrians fled their country in droves. Some risked life and limb to smuggle themselves and their families out of Syria over land, by sea, or any other routes available to them.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Since 2014, hundreds of thousands of Syrians from diverse ethnic backgrounds have managed to escape the violence and atrocities of the civil war by moving to foreign countries.

For Syrians who had just begun to find a new, stable life in Sudan — where they had hoped that violence and destruction would become a thing of the past — the eruption of fighting, looting and displacement in the North African country seems proof that the specter of war will follow them across borders.

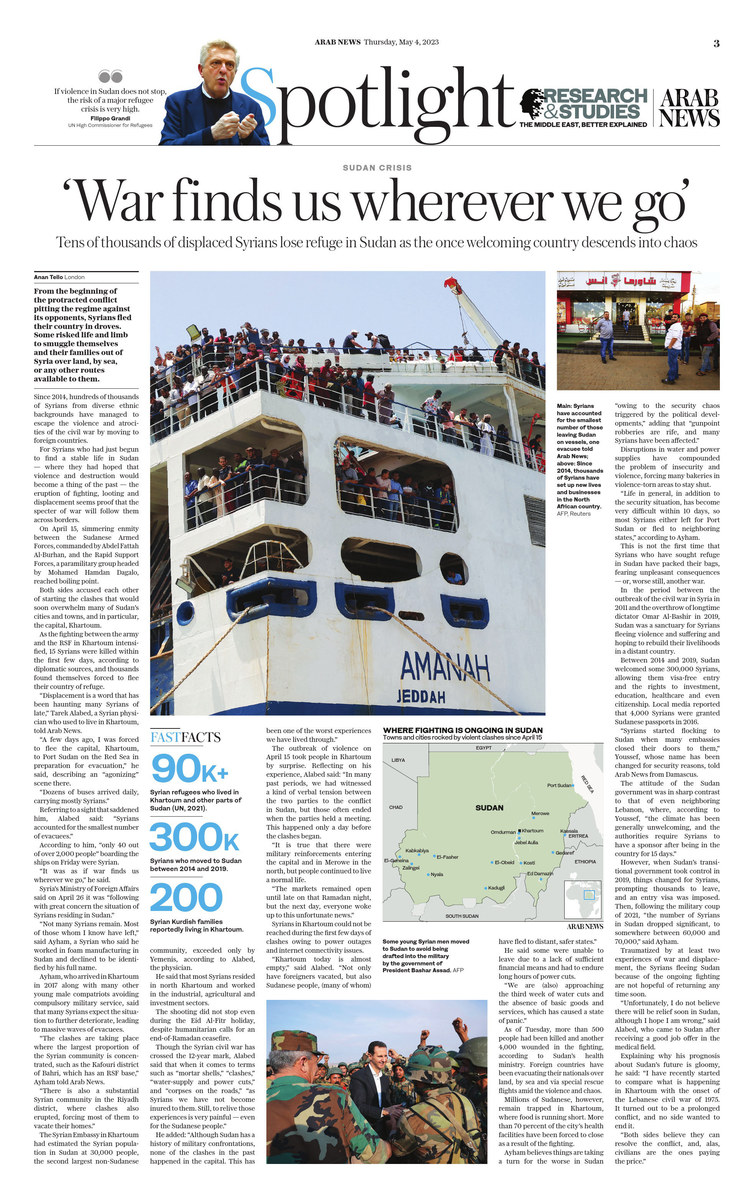

People fleeing war-torn Sudan queue to board a boat from Port Sudan on April 28, 2023. (AFP)

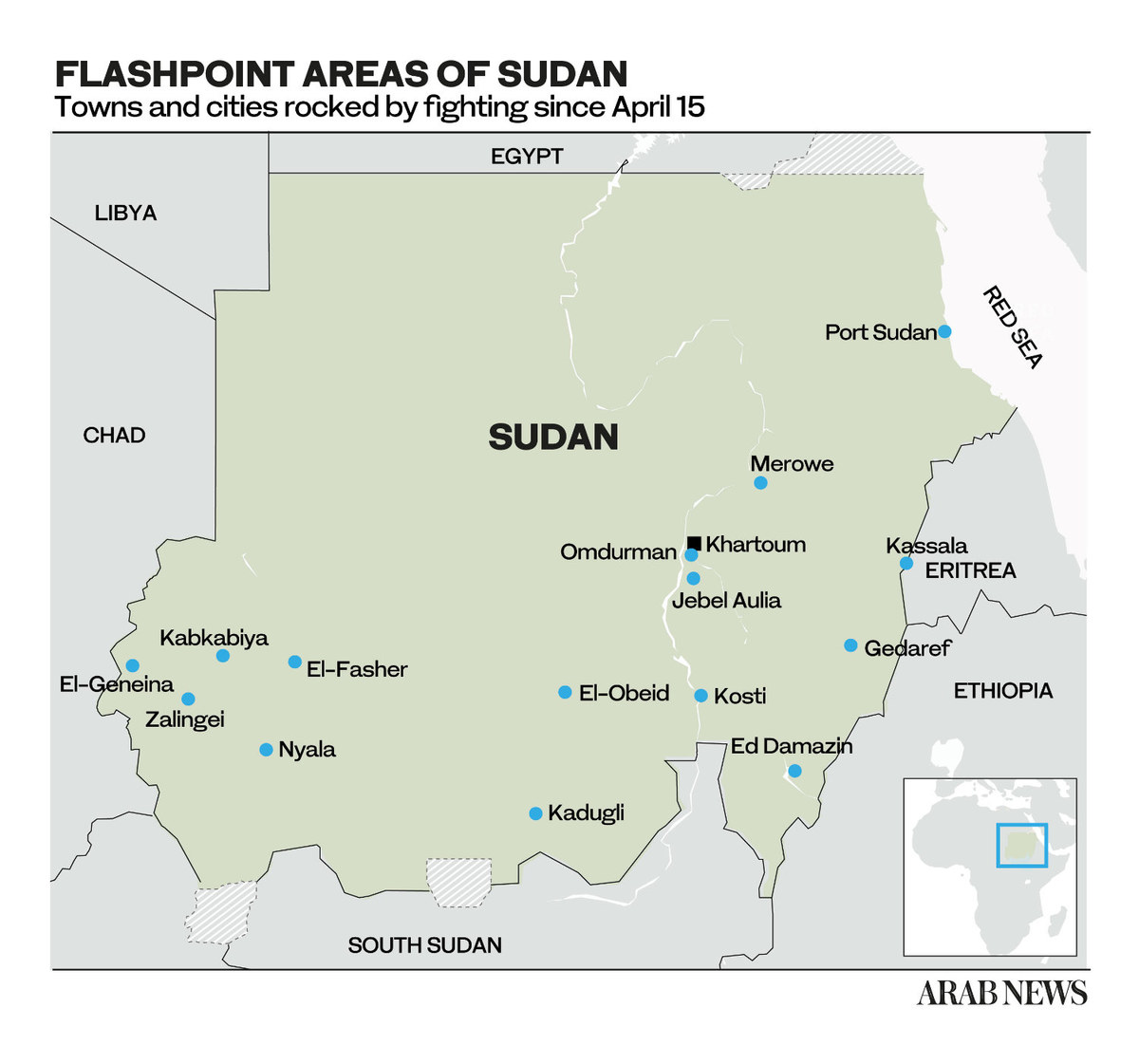

On April 15, simmering enmity between the Sudanese Armed Forces, commanded by Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary group headed by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, reached boiling point.

Both sides accused each other of starting the clashes that would soon overwhelm many of Sudan’s cities and towns, and in particular, the capital Khartoum.

As the fighting between the army and the RSF in Khartoum intensified, 15 Syrians were killed within the first few days, according to diplomatic sources, and thousands found themselves forced to flee their country of refuge.

“Displacement is a word that has been haunting many Syrians of late,” Tarek Alabed, a Syrian physician who used to live in Khartoum, told Arab News.

“A few days ago, I was forced to flee the capital, Khartoum, to Port Sudan on the Red Sea in preparation for evacuation,” he said, describing an “agonizing” scene there.

“Dozens of buses arrived daily, carrying mostly Syrians.”

Referring to a sight that saddened him, Alabed said: “Syrians accounted for the smallest number of evacuees.”

According to him, “only 40 out of over 2,000 people” boarding the ships on Friday were Syrian.

“It was as if war finds us wherever we go,” he said.

Evacuees stand on a ferry as it transports some 1900 people across the Red Sea from Port Sudan to the Saudi King Faisal navy base in Jeddah, on April 29, 2023, during mass evacuations from Sudan. (AFP file)

Syria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement through the Syrian Arab News Agency on April 26, saying that it was “following with great concern the situation of Syrians residing in Sudan.”

The ministry added that it had “made contacts with brotherly and friendly countries to assist in the evacuation process,” highlighting that Saudi Arabia had enabled the departure of hundreds of Syrians from the eastern city of Port Sudan.

“Not many Syrians remain. Most of those whom I know have left,” said Ayham, a Syrian who said he worked in foam manufacturing in Sudan and declined to be identified by his full name.

FASTFACTS

90,000+ Syrian refugees who lived in Khartoum and other parts of Sudan (2021 UN).

300,000 Syrians who moved to Sudan between 2014 and 2019.

200 Syrian Kurdish families reportedly living in Khartoum.

Ayham, who arrived in Khartoum in 2017 along with other young male compatriots trying to escape compulsory military service, said many Syrians expect the situation to further deteriorate, leading to massive waves of evacuees.

“The clashes are taking place where the largest proportion of the Syrian community is concentrated, such as the Kafouri district of Bahri, which has an RSF base,” Ayham said.

“There is also a substantial Syrian community in the Riyadh district, where clashes also erupted, forcing most of them to vacate their homes.”

The Syrian Embassy in Khartoum had estimated the Syrian population in Sudan at 30,000 people, the second largest non-Sudanese community, exceeded only by Yemenis, according to Alabed, the physician.

Syria President Bashar Assad’s crackdown on protesters in 2011 and the subsequent civil war sparked a mass exodus that saw tens of thousands of his countrymen fleeing to Sudan. (AFP file)

He said that most Syrians resided in north Khartoum and worked in the industrial, agricultural and investment sectors.

The shooting did not stop even during the Eid Al-Fitr holiday, despite humanitarian calls for an end-of-Ramadan ceasefire.

Though the Syrian civil war has crossed the 12-year mark, Alabed said that when it comes to terms such as “mortar shells,” “clashes,” “water-supply and power cuts,” and “corpses on the roads,” “as Syrians we have not become inured to them. Still, to relive those experiences is very painful – even for the Sudanese people.”

He continued: “Although Sudan has a history of military confrontations, none of the clashes in the past happened in the capital. This has been one of the worst experiences we have lived through.”

In this image grab taken from footage released by the Sudanese paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on May 1, 2023, fighters stand at an entrance of the presidential palace in Khartoum. (AFP)

The outbreak of violence on April 15 took people in Khartoum by surprise. Reflecting on his experience, Alabed said: “In many past periods, we had witnessed a kind of verbal tension between the two parties to the conflict in Sudan, but those often ended when the parties held a meeting. This happened only a day before the clashes began.

“It is true that there were military reinforcements entering the capital and in Merowe in the north, but people continued to live a normal life.

“The markets remained open until late on that Ramadan night, but the next day, everyone woke up to this unfortunate news.”

Syrians in Khartoum could not be reached during the first few days of clashes owing to power outages and internet connectivity issues.

“Khartoum today is almost empty,” said Alabed. “Not only have foreigners vacated, but also Sudanese people, (many of whom) have fled to distant, safer states.”

A deserted street is pictured in Khartoum on May 1, 2023 as deadly clashes between rival generals' forces have entered their third week. (AFP)

He said some were unable to leave due to a lack of sufficient financial means and had to endure long hours of power cuts.

“We are (also) approaching the third week of water cuts and the absence of basic goods and services, which has caused a state of panic.”

As of Tuesday, more than 500 people had been killed and another 4,000 wounded in the fighting, according to Sudan’s health ministry. Foreign countries have been evacuating their nationals over land, by sea and via special rescue flights amid the violence and chaos.

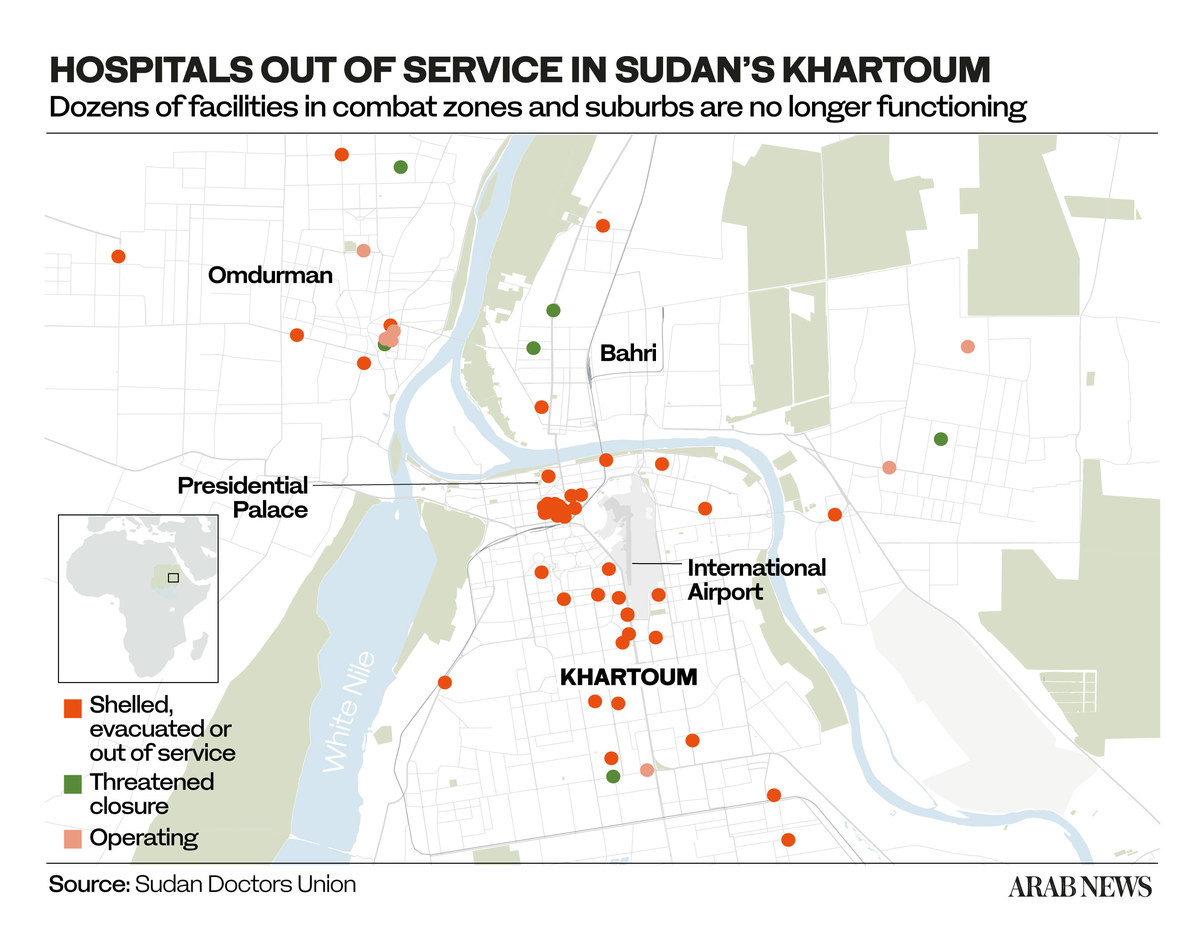

Millions of Sudanese, however, remain trapped in Khartoum, where food is running short. More than 70 percent of the city’s health facilities have been forced to close as a result of the fighting.

On Saturday Abdalla Hamdok, the former Sudanese prime minister, said the conflict could become worse than those in Syria and Libya, which have led to the deaths and displacement of hundreds of thousands of people and caused instability in the wider regions.

“I think it will be a nightmare for the world. This is not a war between an army and a small rebellion. It is almost like two armies,” he said.

In an article published on Saturday, the Norwegian Refugee Council described the situation in Sudan as “the worst-case scenario,” noting that that fuel is running out, many banks and shops have been robbed, and access to basic services, including water, electricity, food and communication networks, are a challenge.

A Syrian woman cooks at the Eve Kitchen (Hawa in Arabic) in Khartoum on November 25, 2015, as part of a project to support Syrians who have fled their war-torn country and taken refuge in the Sudanese capital since 2011. (AFP file photo)

Ayham believes things are taking a turn for the worse in Sudan “owing to the security chaos triggered by the political developments,” adding that “gunpoint robberies are rife, and many Syrians have been affected.”

Disruptions in water and power supplies have compounded the problem of insecurity and violence, forcing many bakeries in violence-torn areas to stay shut.

“Life in general, in addition to the security situation, has become very difficult within 10 days, so most Syrians either left for Port Sudan or fled to neighboring states,” according to Ayham.

This is not the first time that Syrians who have sought refuge in Sudan have packed their bags, fearing unpleasant consequences — or, worse still, another war.

In the period between the outbreak of the civil war in Syria in 2011 and the overthrow of longtime dictator Omar Al-Bashir in 2019, Sudan was a sanctuary for Syrians fleeing violence and suffering and hoping to rebuild their livelihoods in a distant country.

Between 2014 and 2019, Sudan welcomed some 300,000 Syrians, allowing them visa-free entry and the rights to investment, education, healthcare and even citizenship. Local media reported that 4,000 Syrians were granted Sudanese passports in 2016.

Syrians wait outside the Shawermat Anas restaurant in Khartoum. (Reuters File Photo)

“Syrians started flocking to Sudan when many embassies closed their doors to them,” Youssef, whose name has been changed for security reasons, told Arab News from Damascus.

The attitude of the Sudan government was in sharp contrast to that of even neighboring Lebanon, where, according to Youssef, “the climate has been generally unwelcoming, and the authorities require Syrians to have a sponsor after being in the country for 15 days.”

However, when Sudan’s transitional government took control in 2019, things changed for Syrians, prompting thousands to leave, and an entry visa was imposed. Then, following the military coup of 2021, “the number of Syrians in Sudan dropped significant, to somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000,” said Ayham.

Amid the violence in Sudan, Syrians who have fled the war in their country will have to find another place to to go again. (AFP)

Traumatized by at least two experiences of war and displacement, the Syrians fleeing Sudan because of the ongoing fighting are not hopeful of returning any time soon.

“Unfortunately, I do not believe there will be relief soon in Sudan, although I hope I am wrong,” said Alabed, who came to Sudan after receiving a good job offer in the medical field.

Explaining why his prognosis about Sudan’s future is gloomy, he said: “I have recently started to compare what is happening in Khartoum with the onset of the Lebanese civil war of 1975. It turned out to be a prolonged conflict, and no side wanted to end it.

“Both sides believe they can resolve the conflict, and, alas, civilians are the ones paying the price.”