CAIRO: Egypt has long been a favored destination among refugees fleeing conflict, persecution and economic woes in countries across the Middle East and East Africa, either as a place of refuge or a stopover en route to Europe.

Now, with violence and chaos engulfing its southern neighbor, Sudan, authorities in Cairo are braced for a fresh wave of refugees in search of safety, employment and functioning health services. According to a report in the New York Times, more than 15,000 Sudanese have fled the Darfur region into neighboring Chad.

People prepare to board a bus departing from Khartoum on April 24, 2023, as battles rage in the city between the army and paramilitaries. (AFP)

On Sunday, 436 Egyptians were successfully evacuated from Sudan via land. Ahmed Abu Zeid, spokesperson for the foreign ministry, said that evacuations would continue in order to ensure the safe and sound return of all Egyptian citizens.

Already home to a Sudanese community estimated at four million, Egypt offers few of the lucrative jobs that Sudanese migrants have traditionally sought in the Gulf region, but is considered an easier and often more familiar destination.

Due to its geographical proximity and shared history, young Sudanese can travel to Egypt cheaply to search for work, while families can seek health care, education for their children, and perhaps a stable life.

A view of the the Eshkeet-Qastal land crossing between Egypt and Sudan. Egypt has been bracing for an influx of refugees fleeing the raging fight in Sudan between the army and paramilitary forces. (AFP)

Although there are no publicly available figures to show recent migration trends from Sudan to Egypt, authorities say that numbers had been on the rise since 2019, when an uprising led to the overthrow of former Sudanese leader Omar Al-Bashir.

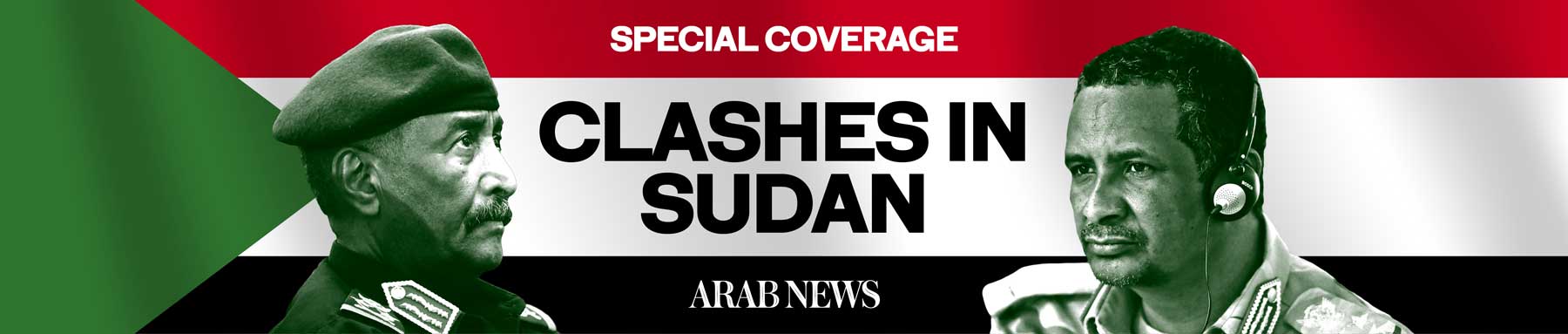

According to Naela Gabr, chair of the National Coordinating Committee for Combating and Preventing Illegal Migration and Trafficking, Egypt is home to about 300,000 registered refugees.

“In addition to the number of registered refugees, there are about nine million foreigners living in Egypt, of whom about four million are Sudanese and half a million are from South Sudan,” Gabr told Arab News.

Infographic from UNHCR Fact Sheet on Egypt for March 2023

“People suffering from political, ethnic or religious conflicts, the latest of which is Sudan, can obtain refugee status in accordance with the UN agreements related to this file. The agreements determine the legality of asylum, and Egypt welcomes any refugee from any country.”

However, owing to the financial burden and social pressures that accepting such large refugee populations can place on host nations and communities, many are concerned about Egypt’s capacity to absorb these numbers.

In this photo taken on March 17, 2011, African workers stuck at the border crossing between Libya and Egypt line up to receive food hand outs from the Red Crescent, amid a refugee exodus during the Libyan revolt against Moammar Qaddafi. Egypt is again facing possible influx of refugees as war rages in Sudan. (AFP file)

`

“As there are in Egypt a large number of immigrants who come to Egypt illegally, illegal immigration is a phenomenon that is difficult to measure, and it is difficult for Egypt to bear it during this period,” Gabr said.

The number of Sudanese seeking refuge in Egypt has risen rapidly in recent years due to repeated bouts of conflict, chronic political instability and economic stagnation in both Sudan and South Sudan.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Whereas in the past many refugees from across the wider region used Egypt and its Mediterranean coast as a jumping-off point for the risky journey to Europe, many are now choosing to stay, taking advantage of the country’s comparative stability.

“The number of illegal immigrants to Egypt will increase in the coming period, as Egypt was a passage for illegal immigrants, but it has turned into a stable country due to border control,” Gabr said.

This photo taken on January 5, 2014 shows thousands of African migrants who entered Israel illegally via Egypt demonstrating in Tel Aviv to dramatize their request for refugee status. Egypt has been a passage way for African migrants but many are now choosing to stay, taking advantage of the country’s comparative stability. (AFP file)

If Sudanese displaced by the current fighting begin to arrive in vast numbers, Egyptian authorities may have to consider establishing formal camps to prevent a humanitarian emergency or a security breakdown.

“If the crisis in Sudan continues and the situation there continues to worsen and becomes a civil war like the Syrian case, the rate of Sudanese refugees will increase by a large percentage,” Mohamed El-Sayed, an Egyptian commentator, told Arab News.

“If it is normal for 1,500 Sudanese to pass through the land crossing every day, the passers will be about 15,000, and then Egypt will have two options.

“The first option is to open the refugee gate without control, and at that time the state will be forced to put them in camps because the state is unable to absorb this number within the country.”

Egypt could be forced to open its border to Sudanese people seeking safety should the war in Sudan continue and the situation worsen. (AFP file)

As for the second option, “Egypt will then have to completely change its dealings with the refugee situation, and asylum will be in accordance with the UN agreements that regulate this matter.

“Egypt will not be able to absorb half of the people of Sudan, as the disaster will be great, especially in light of a severe economic crisis.”

Indeed, if the factional fighting in Sudan escalates, huge numbers could be forced to flee across the border. At least 400 people have been killed in clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in recent days.

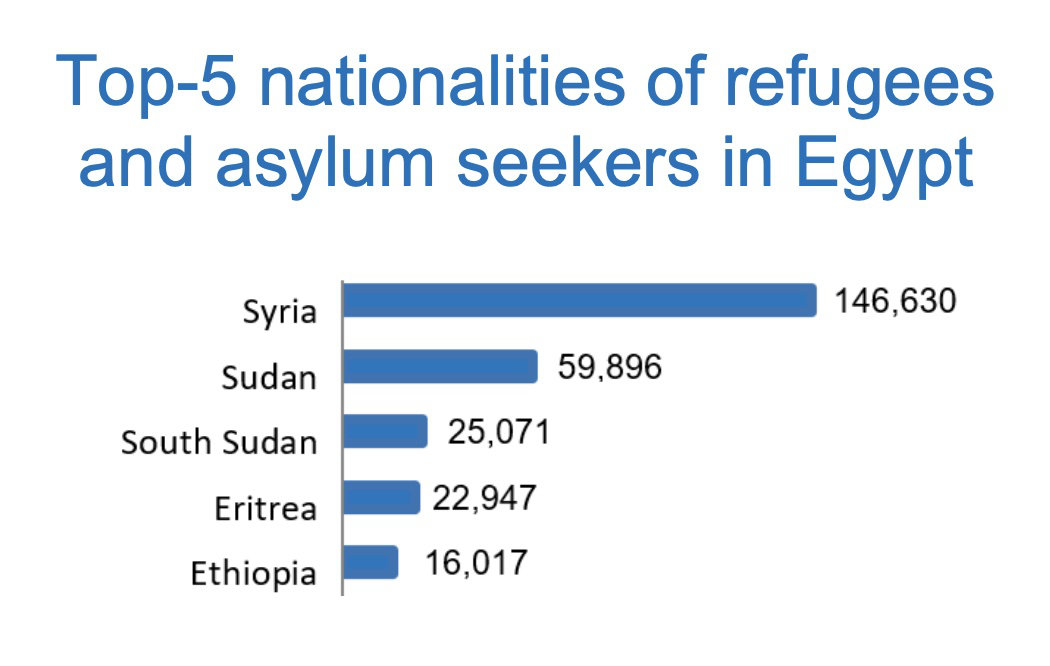

After Al-Bashir was toppled in 2019, an October 2021 military coup dismantled all civilian institutions and overturned a power-sharing agreement that had been put in place.

In this August 17, 2019, photo, Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan (2nd-R) and Mohamed Hamdan Daglo "Hemeti" (3rd-L) celebrate the signing of the "constitutional declaration" that paves the way for a transition to civilian rule. After ignoring the agreement later and seizing power from their civilian partners, the two generals are on each other's throats. (AFP)

Following a massive public outcry, military and civilian actors signed a framework agreement in December 2022 with a view to returning to the path toward civilian-led democracy.

However, a power struggle between the two main military actors in Sudan continued despite the framework agreement, which had stipulated that the RSF would be integrated into the Sudanese Armed Forces.

Gen. Fattah Al-Burhan, head of Sudan's Armed Forces, leads the country’s transitional governing Sovereign Council, while his former deputy, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti, leads the RSF.

Combo image showing soldiers of Sudan's Armed Forces led by Gen. Fattah Al-Burhan and members of the paramilitary RSF led by Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. (AFP file pictures)

Al-Burhan’s Armed Forces had called for the integration to be completed over a period of two years, while Hemedti’s RSF was adamant it should take place over 10 years.

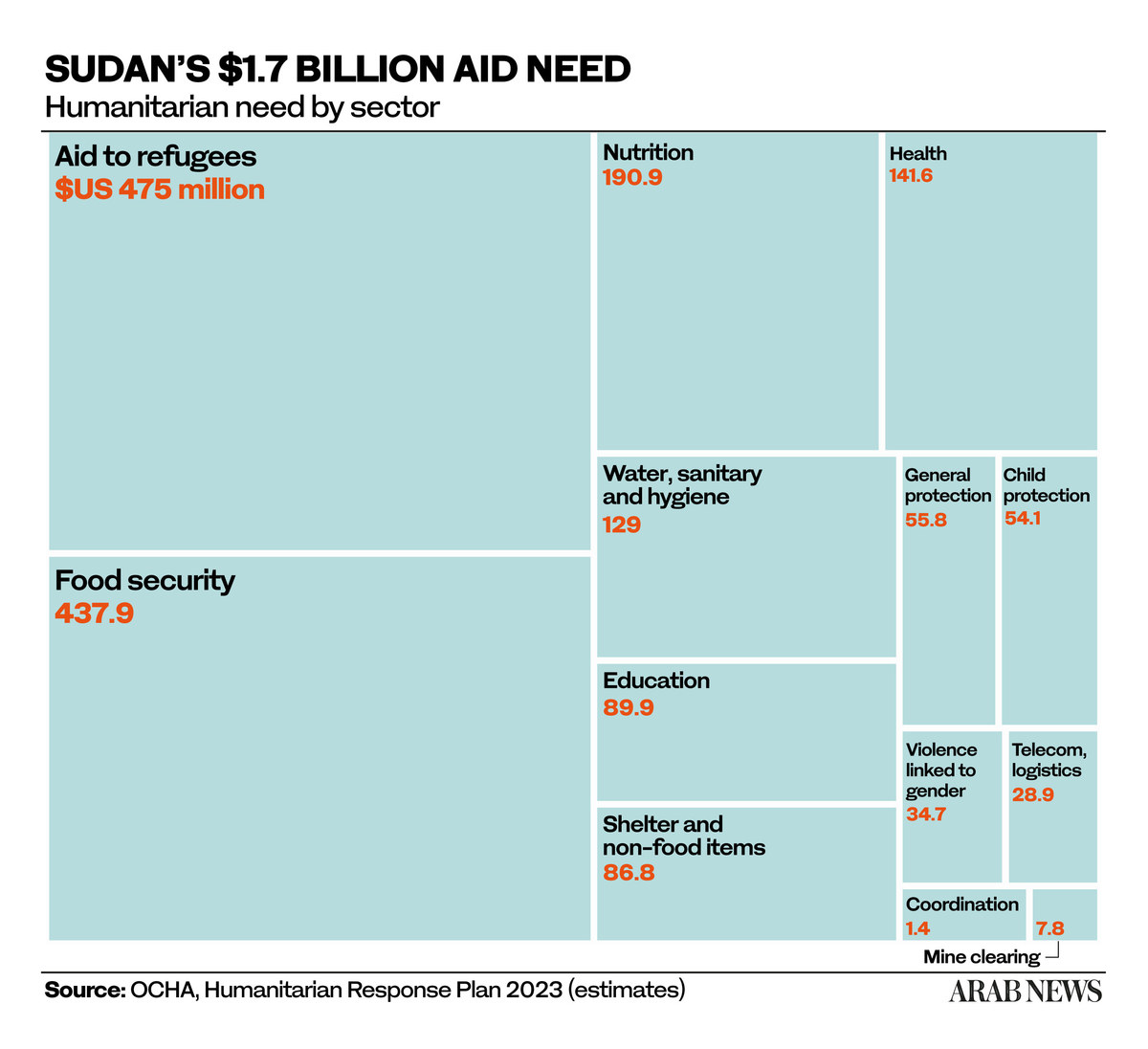

The current fighting in Sudan has aggravated an already dire humanitarian situation in the country. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, OCHA, about 15.8 million Sudanese are in need of humanitarian aid — 10 million more than in 2017.

In February this year, even before the latest round of violence, the UN warned that more than a third of Sudan’s population would need humanitarian assistance in 2023 amid growing displacement and hunger.

OCHA said that about four million children under the age of five, as well as pregnant and lactating women, were among the most vulnerable and in need of lifesaving nutrition services.

Sudan was already one of the world’s poorest countries when the international aid on which it depended was cut in late 2021 in response to the coup that derailed its democratic transition.

In addition to conflict, hunger and malnutrition, Sudan is one of the countries hardest hit by climate change. Widespread flooding last year affected some 349,000 people, sparking a surge in diseases such as malaria, contributing to growing displacement.

Sudan is already packed with refugees from South Sudan and neighboring countries. Should the raging war escalate further, Egypt risks being a destination of more refugees. (AFP)

Economic troubles also deepened following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Circumstances in Egypt are also difficult with inflation running at its highest in almost four years, and almost a quarter of young people unemployed, according to the International Labour Organization.

Sudanese youth living in Egypt often end up working menial jobs in factories or as domestic help. However, they have a community they can lean on and can earn more than they would at home.

Also, members of the Sudanese community already living in Egypt say they feel a close bond to their Egyptian neighbors and are well integrated.

For many Sudanese refugees in Egypt who end up working in factories or as domestic help, the opportunity is much better than having none at all in their homeland. (Getty Images via AFP /File)

Abdullah Al-Mahjoub Al-Marghani, head of the Sudanese Higher Committee for the “Thank You, Egypt” initiative, founded by Sudanese expatriates, believes the community has been treated well.

“The initiative was launched by a group of members of the Sudanese community residing in Egyptian territory, and it comes as a source of pride and appreciation to the people and the Egyptian government for the efforts made for the Sudanese community inside Egypt and their treatment as Egyptian citizens without discrimination,” he told Arab News.

“The Sudanese people fused with the Egyptian people and became one fabric, which is a cohesion that extends throughout history.”