DUBAI: Just under three years ago, Beirut’s Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock Museum was wrecked after several thousand tons of ammonium nitrate exploded in the Beirut Port on August 4, 2020. Parts of the early-20th-century townhouse were completely destroyed, artworks were damaged, and the Lebanese capital’s oldest independent cultural establishment, the center of Beirut’s cultural scene in the 1960s, was forced to close.

Now, thanks to a lengthy reconstruction and funding from various international organizations, it will reopen its doors on May 26 and recommence its programming.

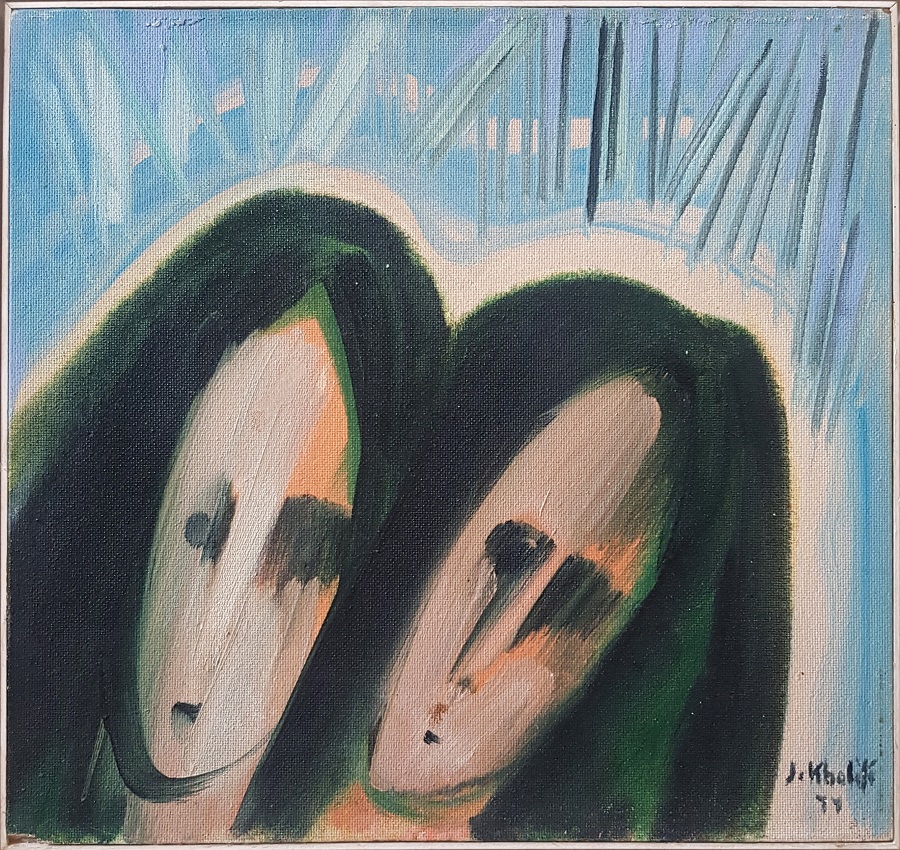

Jean Khalife's 1977 work 'La Peur,' part of the 'Beyond Ruptures' exhibition. (Supplied)

“Despite the ongoing crisis the country is facing, it is important to celebrate the museum and the work that has been done for it to reopen,” Karina El-Helou, who was appointed as director of the museum around six months ago, told Arab News. The museum’s previous director, Zeina Arida, now heads the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha.

“The reopening is not just celebrating the museum, but the people who stayed and worked on it over the past few years as the country continues to face economic collapse,” El-Helou added.

Kees Van Dongen's portrait of Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock, circa 1926-1930. (Supplied)

While the reconstruction was taking place, the museum resumed a few activities, such as art festivals and artists’ talks, but its exhibition spaces have been closed since the explosion. Its reopening, as Lebanon continues to battle several nationwide crises is a feat in itself, symbolizing the city’s resilience and belief in the power of art and culture even — perhaps particularly — during moments of intense hardship.

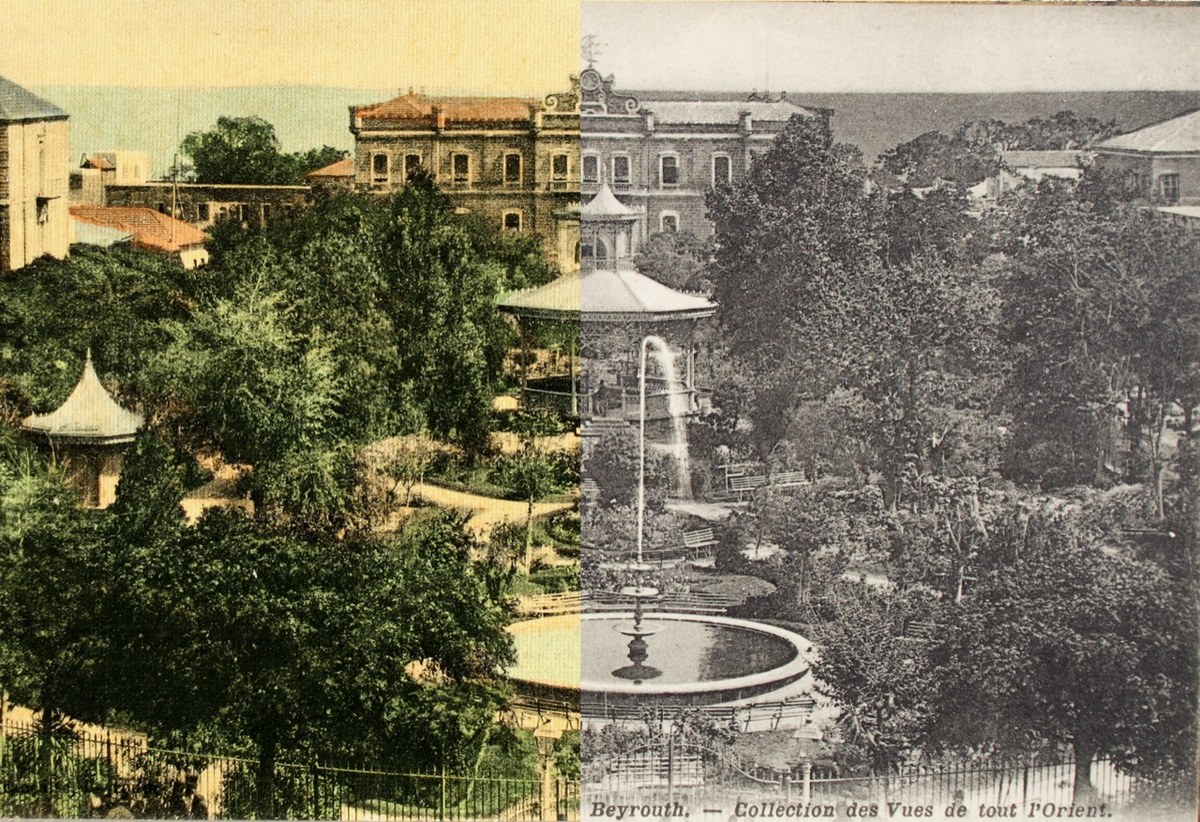

A postcard from the Fouad Debbas Collection before and after the coloring process. (Supplied)

Restoration of the museum included the replacement of all windows — including its iconic stained glass; the repair of all doors, elevators, drop ceilings, and skylights; the repair and cleaning of the electro-mechanical system; and the restoration of the traditional wooden panels on the museum’s historical floor, El-Helou explained.

The museum has raised a total of $2,376,751 since the blast, with both the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas and the French Ministry of Culture providing half a million dollars each, while Agenzia Italiana Per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo (AICS) in partnership with UNESCO-Li Beirut providing $1million.

It wasn’t just the building that was damaged in the blast either. Around 50 artworks have also been restored, including two paintings— “Untitled (Consolation)” by Paul Guiragossian and a portrait by Kees Van Dongen of Nicolas Sursock, the Lebanese art collector who died in 1952 and bequeathed his private villa to the city to be used as a museum — that were restored by the team at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

The museum will reopen with an ambitious program of five exhibitions: “Je Suis Inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the National Canon,” which revisits the legacy of the annual juried Salon d’Automne in Beirut from the Sursock Museum’s inauguration in 1961; “Beyond Ruptures: A Tentative Chronology” exploring three periods of the museum’s history and local socio-political events through works by prominent Lebanese artists including Akram Zaatari, Aref El-Rayess, Jean Khalife and Shaffic Abboud; “Earthy Praxis,” a group exhibition of contemporary works reflecting on land appropriation and ownership in Lebanon; video installation “Ejecta: Zad Moultaka”; and “Beirut Recollections,” an exhibition of photographs from the Fouad Debbas collection and the Paris-based tech-event company Iconem that looks to provide creative solutions to the world’s cultural heritage losses.

It's a remarkable return for an institution whose future was, at points, in serious doubt. And its significance, El-Helou stressed, is considerable.

“We are more than just a museum,” she said. “We represent the memory of Beirut. The situation is still very difficult in Lebanon, but there is a positive energy in the museum now. With so many having left the country, what we stand for is the memory of a city and a country.”