RIYADH: A few months ago, Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit was seen drilling and hammering away on raw granite for her latest Tuwaiq Sculpture piece. As the work took shape and the dust settled, it formed a word far from the harshness of the rock it was carved on — “As-Sami,” “The Ever-Listening,” which is one of the 99 names of Allah.

Mindfully crafting her “99 Names of God” series, Alqunibit seeks, as a Saudi artist, to promote the Islamic faith through public art because she believes it has proven to be a powerful tool to spread a message of kindness and peace.

Alqunibit told Arab News: “When I came back to Saudi Arabia (in 2017), I didn’t find a lot of religious art. I didn’t find our identity or calligraphy within our culture or within the art. I saw a lot of abstract modern art, but our identity is just starting (to form).”

Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit is drawn to creating public art installations because their very existence in a common space makes art accessible for all. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

Alqunibit’s work has caught the eye of audiences across the globe, from American exhibitions and Dubai-based galleries to Saudi Arabia’s very own National Museum.

Her relationship with art flourished while accompanying her son and daughter during their studies in Portland back in 2009. Initially carrying a human resources degree, she was inspired by the art in the Oregon State city — public works scattered in park areas, and colorful murals on the walls of metro stops and neighborhood blocks.

“I thought, because I’m here, I want to learn and take this whole experience back home, to my country to show and teach people,” she said.

Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit working on a stone public art sculpture. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

She went on to apply for a degree in art, but having no tangible work in the US she was left with two choices: to put on a fully-fledged art exhibition in order to determine her level, or to move on from her human resources degree and start from scratch.

She chose the latter and was eventually honored by being placed on the dean’s list upon graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts and a Sculpture Master of Fine Arts from Savannah College of Art and Design.

Her period of study from 2010 to 2016 was marked by extreme discrimination against Muslims in Western countries, especially in France and the US, and the uncertain political state of the world. “Everyone said ‘this is the doing of Muslim people.’ As an artist, I present my identity and religion. It’s my responsibility to show the behavior of a Muslim through art. This is the language I have. I don’t have any other language,” she said.

Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit is drawn to creating public art installations because their very existence in a common space makes art accessible for all. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

She intentionally contrasts the harsh notion that terrorism is synonymous with what is fundamentally a religion preaching mercy and tolerance. In something so rough and heavy as stone, she intends to create beauty. “We teach kids these meanings. We are a peaceful religion, not a terrorist one,” she said.

Numerics became prominent in her work, and she was even dubbed “Artist Number 5” by her contemporaries due to her tendency to create concepts that explore the five daily prayers in Islam — a title she claims proudly.

In navigating ways to create a modern interpretation of the religion and to reach audiences of all backgrounds, she found that abstract calligraphy provides room for contemplation and introspection. It demands the viewer to not only look but see.

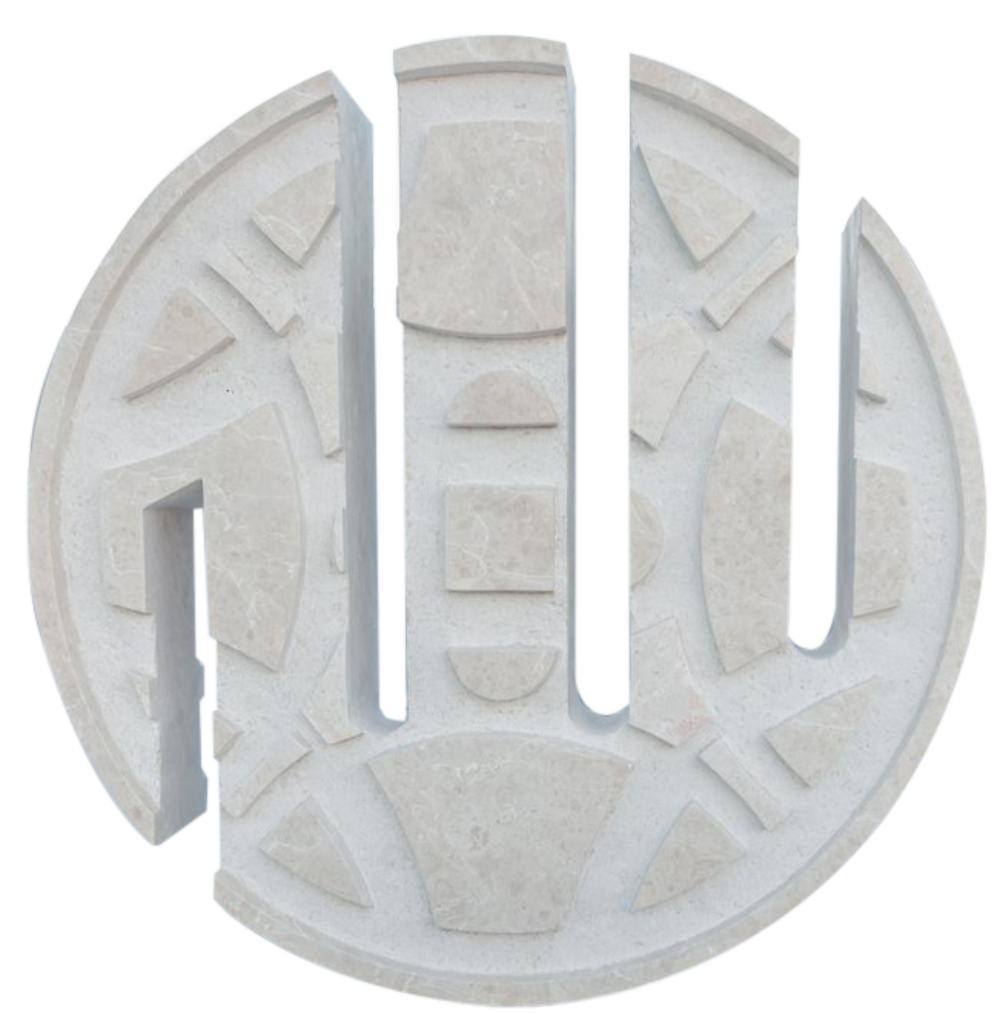

Pieces from Wafa Alqunibit’s 'Power of the Name' exhibition. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

She was drawn to creating somewhat grandiose public art installations because she believes their very existence in a common space invites discourse into the meaning and intention behind the work. It even invites non-aesthetes to comfortably step into the art world, and eventually into a gallery.

Thus was born Alqunibit’s “Al-Asma Ul-Husna” (“99 Names of Allah”) series, a sculpture collection of the qualities attributed to God in Islam, each carrying a unique meaning and context.

Her thesis exhibition, titled “The Power of the Name,” contrasted rough metal pieces with the serenity of the words they shaped. The exhibition was also showcased later in Riyadh, her debut in Saudi Arabia, followed by a second at the National Museum. Both shows were inaugurated by Prince Sultan bin Salman.

From Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit's sculpture series, woman in prayer, which features miniature figures displaying the four positions of prayer. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

From her recollections, 2010 to 2014 was a time of equating terrorism with Islam, with bombings in the UK in 2012 and France in 2013. And the hijab was the global symbol.

She titled her first official show in the US in 2012 “Women Under the Veil,” a series of four paintings, each covered in a fabric that extended to the entrance of the gallery. As members of the audience walked in, they were meant to wonder where the textiles would lead, which was to beautiful artwork underneath. “This is what we are,” Alqunibit said.

This was the defining moment in her career, which was to conceptualize her aesthetics.

Saudi artist Wafa Alqunibit is drawn to creating public art installations because their very existence in a common space makes art accessible for all. (Photo by Wafa Alqunibit)

She recalled a standout moment as a student when one of her professors at SCAD’s sculpture department told her: “You taught us. We learned from you what Islam means. You have that energy in your studio, and we always feel a kind of relaxation in your exhibitions that we don’t feel anywhere else.”

After that, she believed she had left her thumbprint on the country.

So what keeps her going? Why has she positioned herself as a spokesperson for religion in the art world? While the radio was on in her studio one day, a common occurrence during her work, Egyptian preacher Amr Khaled came on. He spoke of the bombings in either France or the UK, Alqunibit recalled.

“Why did you do this?” he spoke generally about terrorist actions. “You have many languages: music, acting, painting, writing. Use these to speak to the people. A bomb will do nothing. Take a language they understand and speak through it.”

Through art, her voice booms. For hijabis, many of whom are the first targets of violence against Muslims, the cause is evident. “From this speech by Amr Khaled, I kept going on.”

With the goal of spreading the message of peace, she hopes the world will finally sit up and listen.