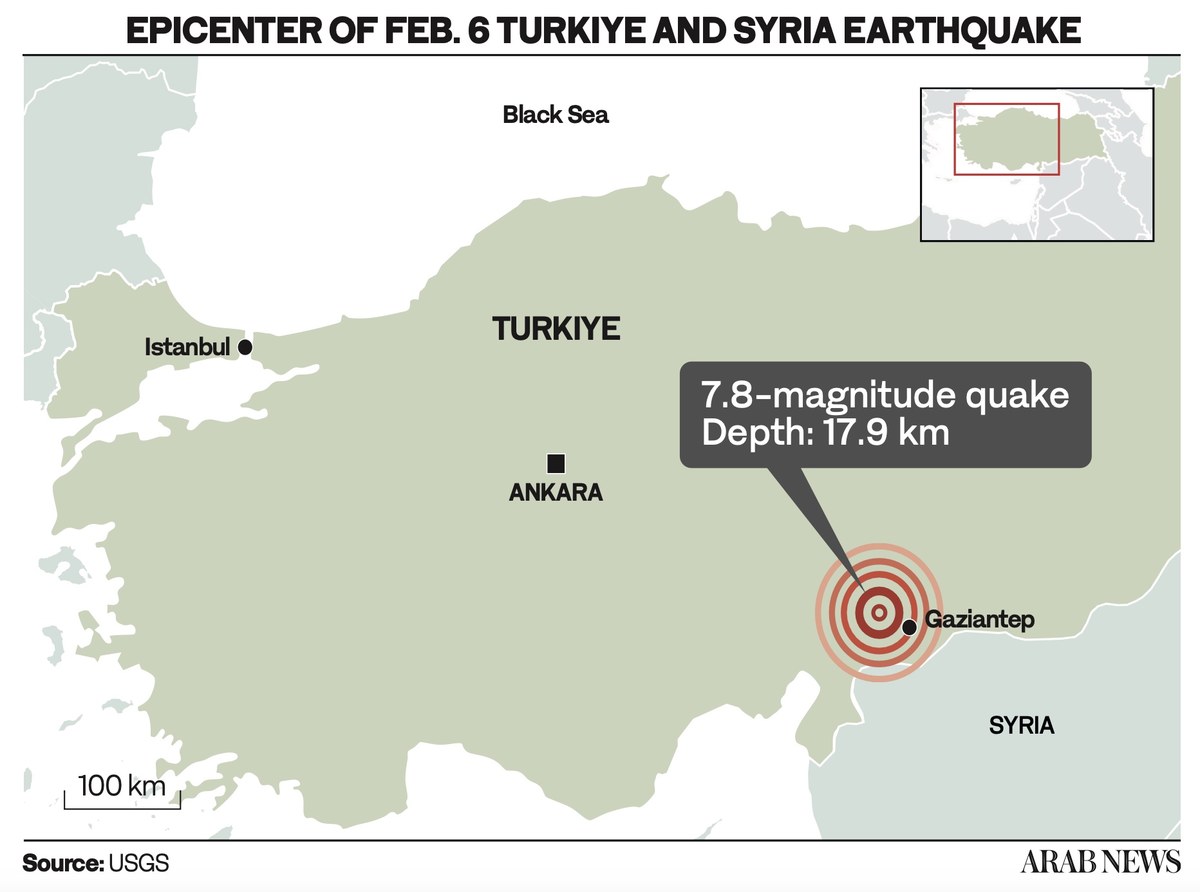

DUBAI: In the early hours of Feb. 6, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck southeast Turkiye and northwest Syria, leaving more than 25,000 dead and at least 80,000 injured.

Humanitarian aid has been trickling into the region over recent days. However, there have been discrepancies in the scale of support reaching the two countries.

In part, this is the result of logistical challenges in a region blighted by political divisions and poor infrastructure. But another factor is politics.

Dr. Hossam Elsharkawi, regional director for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, or IFRC, believes political tensions must be kept out of the humanitarian response.

Dr. Hossam Elsharkawi being interviewed by Frankly Speaking host Katie Jensen. (Screenshot from AN video)

“The focus for us is saving lives and minimizing the suffering to the extent possible with the resources we have — often limited resources — to do this type of work,” Elsharkawi told Katie Jensen, host of “Frankly Speaking,” the Arab News talk show which engages with leading policymakers and business leaders.

While aid began to arrive relatively quickly in Turkiye’s earthquake-stricken southeast, several factors have contributed to delays, complicating rescue efforts and humanitarian relief operations in northwest Syria.

Frankly Speaking host Katie Jensen. (Screenshot from AN video)

Syria is currently divided into three regions governed by various factions, including opposition and other militant groups in the country’s northwest, a Kurdish-led autonomous administration in the northeast, and the Syrian government in the center and south.

The only border crossing for UN aid from Turkiye into Syria, Bab Al-Hawa, was forced by quake damage to close, causing a three-day delay in deliveries into Syria’s northwest.

Asked whether the Bashar Assad regime or international aid organizations bear any responsibility for the additional suffering of the Syrian people, Elsharkawi said: “As humanitarians, we don’t actually blame anyone.

The White Helmet volunteers rescue a child from under rubble in Jandaris, Syria, on Feb. 8, 2023, in the aftermath of a deadly earthquake. (The White Helmets/via REUTERS)

“We deal with the consequences of failed diplomacy, failed politics, and we deal with the humanitarian consequences by focusing on assisting just average people, average families who have been affected for 12 years — and now more severely because of two massive earthquakes.”

After the earthquake, Bassam Sabbagh, Syria’s ambassador to the UN, said the Syrian government should handle all humanitarian aid deliveries, including those going to areas not under the control of Damascus.

Some observers view the Assad regime’s call for sanctions to be lifted as an opportunistic political gambit.

Elsharkawi said aid workers do their jobs without concern for politics. “I have dealt with many Syrian professionals, doctors and nurses and other emergency response people who work in the public authorities who are not politicized.”

“They’re caring, they want to care and scale up assistance for their people. Syria is not a failed state. Its public authorities continue to provide for their people, and we need to be respectful of that.”

An Indonesian search and rescue team load government relief aid onto a C-130 cargo plane in Jakarta on February 11, 2023 for transport to quake-hit Turkiye and Syria. (AFP)

Elsharkawi continued: “What I have observed for years and years is that the assistance has been coming through other channels through Iraq and through Turkiye. So, we work with that. We don’t comment on that.

“We just work with what is possible. Humanitarian assistance in these conditions is partly also the art of the possible, but we’re also beginning to get good news.”

Elsharkawi was referring to Washington’s decision to lift the ban on financial transfers to Syria. “This is significant. We can already see how this crisis has affected the politics of 12 years in a good way to save lives,” he said.

“We hope other sanctions are lifted as well, for example, for procurement of certain supplies and goods and by other nations. So, this is what gives us hope as well, that we can continue to scale up the operation.”

‘We don’t take sides. We just work with what is possible. Humanitarian assistance in these conditions is partly also the art of the possible.’

Dr. Hossam Elsharkawi

In addition to accessibility issues, Elsharkawi said the major reason for the discrepancy in the provision of aid to Turkiye and Syria is the impact of the latter’s grinding civil war on public infrastructure.

“The systems, the response mechanisms in Syria … and infrastructure have largely eroded and been destroyed because of the 12-year war. So, it’s a tale of two very different responses,” he said.

According to the UN, at the beginning of 2023, more than 15 million Syrians were in need of humanitarian assistance.

A recent report by the Washington-based Middle East Institute found that 65 percent of northwest Syria’s infrastructure had already been damaged or destroyed prior to the quake, and that the region is home to almost 3 million internally displaced persons.

Both Syria’s Assad and Turkiye’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan have faced criticism for their handling of the disaster in their respective countries, with some in the latter accusing the government of failing to prepare sufficiently.

Syrians, displaced as a result of the earthquakes that hit Turkey and Syria okn Feb. 6, settle on an open area on the outskirts of the rebel-held town of Jandaris near Aleppo. (AFP)

Elsharkawi thinks this assessment is unfair. “It’s very difficult to prepare 100 percent for these massive events,” he said. “And, remember, we had two massive earthquakes, over magnitude 7, within hours of each other.”

He recalled his experience coordinating humanitarian aid in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, which killed almost 20,000 people.

“Even one of the most developed, industrialized capable countries in the world back then … struggled to deal with that earthquake. So, yes, I understand people want their needs and supplies immediately, but from what we observe, the Turkish Red Crescent, the Turkish Emergency Response Authority and the government are doing their best with the resources they have,” Elsharkawi said.

Turkiye’s handling of the disaster has nevertheless brought perceived ethnic and regional disparities to the fore, with many among the Kurdish minority living in the country’s south blaming authorities for the prevalence of poorly built housing, despite the introduction of new building codes in recent years.

“Crises can make tensions worse, and they can actually also reduce tensions if aid is distributed equitably — if we get people talking and focused on the humanitarian mission and saving lives,” said Elsharkawi.

“People remember when you’ve saved their sons and daughters, and they remember it for a long, long time, and it makes for easier relations sometimes.

“I will not comment on the politics, but, yes, it is possible to prepare and build back better. You can build earthquake-resistant structures, homes, hospitals, and schools. Having codes is one thing. Enforcing the codes is another. So that’s a challenge for many governments around the world.”

Elsharkawi said the IFRC would work with local authorities in future to make sure that enforcement mechanisms are in place for the construction of earthquake-resistant buildings.

Relief supplies from donors in Germany fare prepared for transport near BER Berlin-Brandenburg Airport in Schoenefeld, near Berlin, Germany, on Feb. 9, 2023. (AP)

“That will protect people in the long term,” he said. “If you take 7.5- or 7.8- magnitude earthquakes in Japan, this would not have fazed them because they are building structures that are resistant to earthquakes that are 8 and 9 magnitudes. So, it’s possible. The technology is there. We’ll have to work in the longer term to bring that to the region.”

In the short term, as the IFRC and other agencies deploy personnel and materials to the region, coordination between providers of humanitarian aid will prove critical to preventing the overabundance of some resources and shortage of others, said Elsharkawi.

“We try to do it in a coordinated fashion, for example, to make sure not everybody gives only blankets and mattresses, while the people may also need water, food and medicine. It is critical that we hit the priority needs all at once and not have way too much of one item and nothing of another.”

Several countries, including the UAE, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, China and Venezuela, among others, have provided immediate aid such as food, blankets, tents, generators, fuel and medical supplies.

Elsharkawi highlighted the importance of Saudi Arabia’s contribution toward ongoing rescue efforts and aid.

The Saudi search and rescue team participates in the relief efforts of earthquake victims in Turkey and Syria. (SPA)

“Saudi assistance is vital,” he said. “They’ve asked us for the list of priorities as well to try to customize the assistance and what gets loaded on those planes. So, it is meeting the real needs and the gaps and is tremendously appreciated. It makes a huge difference in saving lives.”

The “Sahem” fundraising campaign, launched by Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center, or KSrelief, two days after the quake, raised more than $53 million for the victims and survivors of the disaster within 48 hours.

King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman also directed KSrelief to begin the operation of an aid “air bridge” to immediately deliver relief supplies to earthquake-stricken regions.

“This is happening as we speak, and will continue to happen as we speak, and we’ll continue to fine tune the content of those air bridges,” Elsharkawi said, adding that inclement weather and a cholera outbreak in Syria necessitate customization of aid.

Sixth Saudi relief plane heading for earthquake-hit areas in Syria and Turkiye. (SPA)

Despite a litany of problems, many countries have put politics aside in order to do their part.

“This is what we are appealing to all to do, in fact — focus on the humanitarian imperative and put aside the politics for a few weeks, a few months perhaps,” Elsharkawi said, adding that the provision of aid may require an even longer commitment.

The IFRC has called for $200 million in aid for both Syria and Turkiye.

“This is a massive assistance package that will be required not just for days and weeks. We’re looking here for a two- to three-year program because we know what it’s like to respond to these massive earthquakes and disasters,” Elsharkawi said.

“We hope that the international and regional nations will be generous with their donations and contributions.”

Elsharkawi disclosed that the IFRC is in contact with countries that would like to assist Syria in spite of the ongoing sanctions. “This is quiet diplomacy that we do, and this is the glimmer of hope that I’m talking about,” he said.