As the year closes, it is possible to discern certain themes of the last twelve months that will continue in cricket for the next.

First, is COVID-19. It delayed the 2020 T20 World Cup until Nov. 2021, as well as forcing its move from India to the UAE and Oman.

At the same time, it disrupted England’s Ashes tour to Australia. A Test scheduled for Perth in January was switched to Tasmania at short notice because of border restrictions in Western Australia.

All of this seems a long time ago. Since then, England won the T20 World Cup and nine of its last 10 Tests.

Elsewhere, COVID-19’s effects can be seen in other tournaments still awaiting completion. There is regional interest in the 2023 ODI World Cup, scheduled for India in October 2023. Both Oman and the UAE are striving to finish in the top three out of seven in League 2 of the qualifying stages so as to progress to the next level.

England won the T20 World Cup held in Australia in 2022. (AFP)

Each team has 36 matches to complete. Although Oman has achieved this, the UAE still has another 10 to fit into a crowded schedule.

A second theme is not COVID-19-related. The Asia Men’s Cup is due to be held in Pakistan in September 2023. The secretary of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, who is also president of the Asia Cricket Council, stated in early October that the Indian team would not travel to Pakistan and that it would be played at a neutral venue.

This incensed Pakistan’s Cricket Board Chair, Ramiz Raja, who was forthright in responding that Pakistan could boycott the 2023 ODI World Cup in India.

Raja was an appointee of Imran Khan, who was removed as prime minister in April after losing a vote of no confidence in Parliament.

It has been a surprise that Raja has remained in post since that time. However, as the year ends, he has been replaced as PCB’s chairman by Najam Sethi, who resigned from the same post when Khan became PM in 2018.

The country’s prime minister is patron of the PCB and has ultimate power of suspension. This has extended to the repeal of a new constitution introduced in 2019 and the restoration of a former 2014 constitution that will see reversion to the game’s previous domestic structure.

Quite how much the removal of Raja and his fellow administrators is a result of his increasingly belligerent language towards the BCCI is a matter of conjecture.

Sethi has made a point of saying the decision to play in India will be taken at government level.

Ramiz Raja said Pakistan could boycott the 2023 ODI World Cup in India. (AFP)

Unsurprisingly, Raja is incandescent, but it seems that his time has gone. It is unlikely to be any consolation for him that the new chairman has appointed the popular, but enigmatic, former player, Shahid Afridi, as interim chief selector. The next year has the ingredients for another enthralling installment of Indo-Pakistani relations on and off the cricket field.

There is a related ingredient simmering in the background. It is understood that the ICC requests the host nation to secure tax exemptions from its national government for tournaments organized by the ICC.

However, India’s tax regulations do not allow such exemptions.

In the 2016 T20 World Cup, held in India, this meant that the BCCI lost around $22 million, as the ICC deducted that amount from the BCCI’s revenue share. A legal battle ensued.

This is clouding current negotiations relating to the 2023 ODI World Cup. It seems that the Indian government plans to levy a 21.84 percent tax surcharge on ICC’s broadcast revenue from the event. This is what the ICC seeks to gain exemption from, but the BCCI has so far not managed to reach a solution in its discussions with the finance ministry.

Further brinkmanship is likely, well into 2023.

Although there are signs that cricket in 2023 will be less disrupted by the pandemic than previously, a third theme re-surfaced in 2021 to cast a long shadow over parts of the sport.

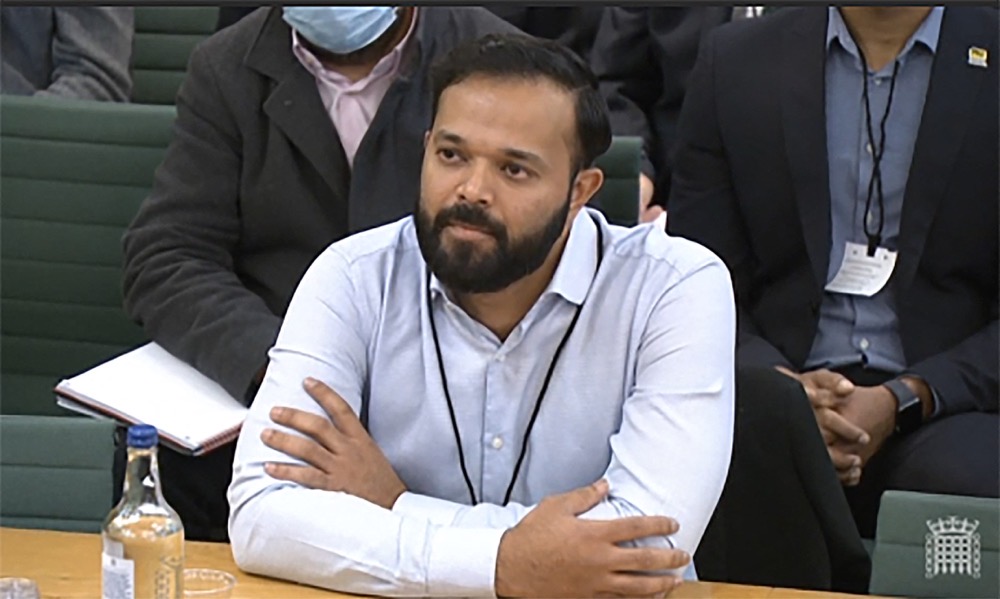

The case of Azeem Rafiq and English cricket, specifically Yorkshire County Cricket Club, blew up in spectacular fashion in Nov. 2021. Rafiq’s harrowing testimony to a Parliamentary Select Committee and the English and Wales Cricket Board representative’s supine responses and attitudes laid bare the conflicted and conflicting understanding of what constitutes racism in cricket.

Azeem Rafiq told UK lawmakers he and his family had been subject to levels of abuse sufficient to cause him to leave the country. (AFP)

Almost immediately, the Chair and CEO of Yorkshire resigned, swiftly followed by the departure of coaching and some administrative staff. Major sponsors withdrew support. A new chairman, Lord Patel, was appointed and, in turn, new coaching staff arrived.

Meanwhile, the ECB seemed traumatized. Its CEO left in June 2022. A new one starts on Jan. 1, while a new chairman joined in August. The report of the Independent Commission for Equity in Cricket will not be published until early 2023. Individuals charged by the ECB in June have yet to have their cases heard.

Two weeks ago, Rafiq revealed, in a return appearance to the Parliamentary Select Committee that, despite 24/7 security, he and his family had been subject to levels of abuse sufficient to cause him to leave the country.

In the space of a year, Rafiq’s search for justice has borne little but heartache, frustration and delay.

It is to be hoped that 2023 heralds positive measures to counter racism in the game. Resolution of the deadlock in Indo-Pakistani relations is also needed if both countries are to participate in two major tournaments.

Intriguingly, the year will also witness a contrast between a rush of T20 tournaments, an ODI World Cup and, possibly, much rejuvenated Test cricket.