BEIRUT: Lavish lunches in mountain-top restaurants overlooking Lebanon’s valleys. Engagement parties at high-end clubs. The joyous Christmas dinner with family and loved ones. Mark Maher is going all out for the Christmas season in Beirut — so much so that he and his friends made a shared calendar to keep track of all his plans.

Friday kicks off with sunset drinks at the swanky Hotel Albergo rooftop, followed by pub-hopping through Badaro’s bar-lined streets and capping the night off with a table at the ever-packed seaside AHM club.

Young Christians from Iraq, Syria and Lebanon light candles before a Christmas mass at Saint Georges church in an eastern Beirut suburb. (AFP/File)

Maher, a finance analyst at a well-known bank, lives in Paris. His friends are spread throughout the French capital, London, New York, and Dubai. Each of them earns a generous salary in their respective local currencies, and Christmas is the rare time of year that brings them all together again, with gifts for loved ones back home taking up most of the space in their suitcases.

Jocelyn, a barista in one of Beirut’s hip cafes, has no shared calendar or lavish plans. Every Lebanese pound she earns is accounted for. There will be no grandiose turkeys with rice and stuffing, nor will there be gadgets galore underneath a glowing tree.

Mark and Jocelyn’s contrasting Christmases lay bare Lebanon’s 2019 economic collapse that has held residents’ bank accounts hostage. Jocelyn, who earns her monthly salary and tips in Lebanese pounds, follows the ever-changing currency rate like clockwork.

What started off as a monthly wage that would amount to $1,500 has now dropped to around $200.

“It’s been a very rough couple of Christmases,” Jocelyn, who did not want to give her full name out of fear of retribution from employers, told Arab News.

FASTFACTS

• $112 Median monthly income for a household in Beirut.

• 82% Poverty rate in Lebanon.

• 79,134 Emigrants from Lebanon in 2021.

“First, we had the protests, and the economy wasn’t doing well, then the coronavirus pandemic, and then the explosion,” the mother-of-two said, referring to the Aug. 4 Beirut port blast that left more than 300 people dead and struck another crippling blow to the Lebanese economy. “We hoped this year we could have a dinner that’s close to what we had before, but I don’t think it is possible.”

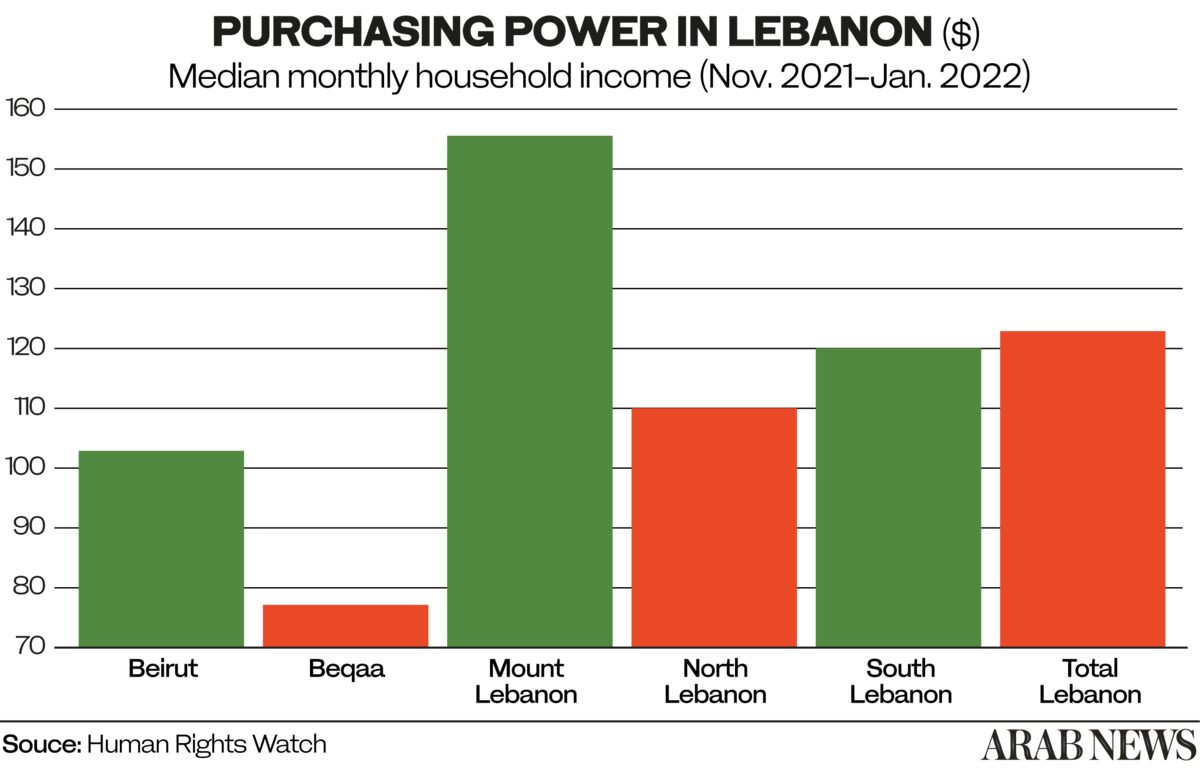

According to a Human Rights Watch report, the median monthly income for a household in Beirut as of 2022 stands at $112. In the more impoverished Bekaa region, it is $78.

Maher, on the other hand, has benefitted from the currency collapse. A regular night out on the town, wining and dining with friends, would have cost at least $70 per person. Now, with the fluctuation of the lira against the dollar, the bill for a top-shelf Lebanese meal and drink comes to $30 at most.

“Before, we used to go out twice a week as it was too expensive; now we live like kings when we come back with fresh dollars,” Maher said.

With many citizens’ hard-earned savings stuck in banks, the term “lollar” was coined to reference US dollars stuck in the banking system. The system, which was set by banks to prevent a run on the banks, has driven multiple people to literally hold banks hostage in order to withdraw a few hundred dollars from their own accounts.

The poverty rate in Lebanon doubled from 42 percent in 2019 to 82 percent of the total population in 2021, with nearly 4 million people living in multidimensional poverty.

According to a Human Rights Watch report, the median monthly income for a household in Beirut as of 2022 stands at $112. In the more impoverished Bekaa region, it is $78. (Supplied)

The country itself seems to be turning a blind eye to the wide chasm in wealth among classes, making for surreal, paradoxical moments. A tall Christmas tree made of luxury, designer-made handbags towers over scattered shoppers in a quiet shopping center.

Restaurant meals and products across the capital are sold in US dollars. A billboard advertises investment opportunities in Cyprus and Portugal that could lead to a passport — for those who can spare $100,000.

As Lebanon inevitably enters the new year without a president, its politicians are not worried. Expats continue to fly home in droves to spend the holiday with their family and friends, all while pumping fresh dollars into the economy.

As for those who cannot leave, they endure yet another candle-lit Christmas as they wait for the electricity to come back on.