LONDON: It was, in the words of a 1998 report published in Scientific American, “the day the sands caught fire.”

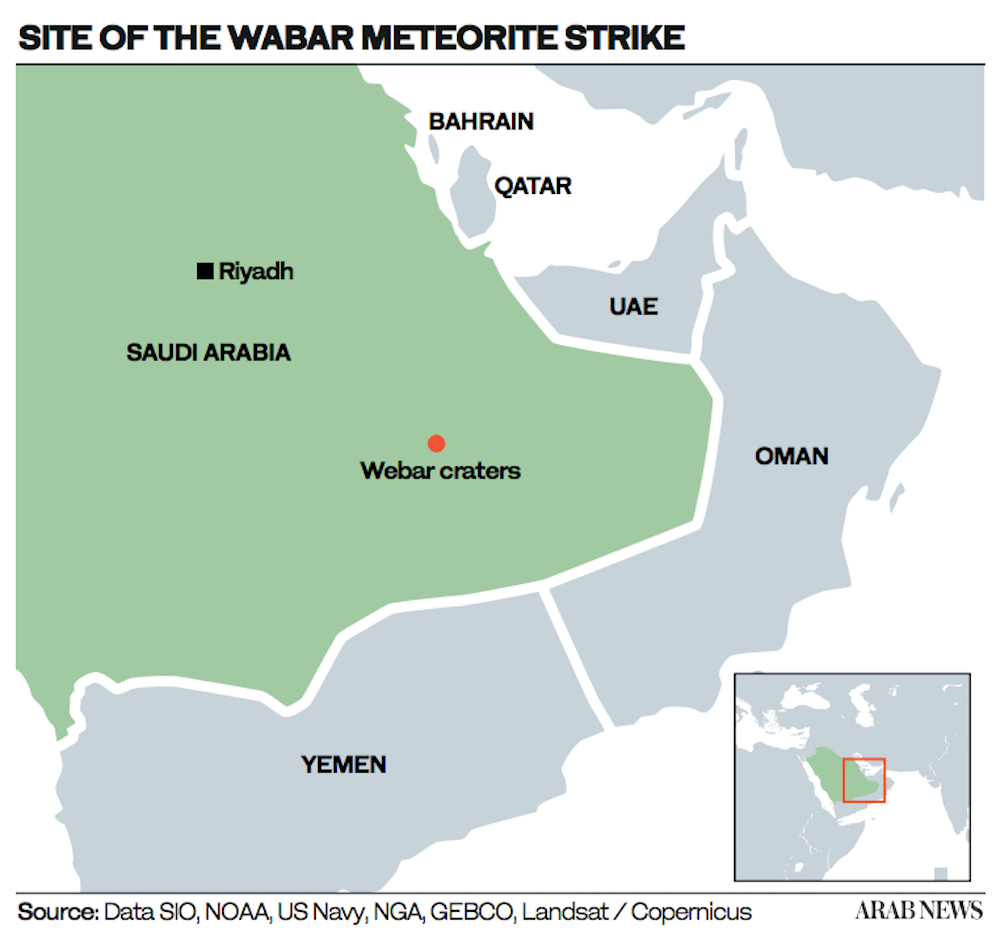

The sands in question were at an isolated spot deep in Saudi Arabia’s Rub Al-Khali, or Empty Quarter. The fire, which melted half a square kilometer of desert and transformed it into black glass, fell from the sky in one of the most dramatic meteorite strikes the planet has ever experienced.

Geologists continue to debate exactly when the so-called Wabar meteorite fell to Earth — the theories range from 450 to 6,400 years ago. However, we can be almost certain that this ancient traveler, carrying fragments of celestial bodies that formed in the earliest days of our solar system, originated in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Having orbited the Sun for millions of years, it finally crashed into Earth’s atmosphere at a speed of up to 60,000 kilometers per hour, before plummeting to Earth in several fiery pieces.

However, it was a more down-to-earth mystery that, 90 years ago, led intrepid British explorer Harry St. John Philby to the edge of two craters in the desert so imposing that, at first, he mistook them for the mouths of an extinct volcano. He was pursuing the legend of an ancient lost city in the heart of the sands, described in the Qur’an as having been destroyed by God for rejecting the warnings of the prophet Hud.

In 1930 and 1931, British explorer Bertram Thomas had become the first Westerner to cross the Empty Quarter. In his 1932 book, “Arabia Felix,” he recounted how his Bedouin guides had shown him “well-worn tracks, about a hundred yards in cross-section, graven in the plain.”

They led north into the sands at the southern edge of the vast desert. This, the guides told Thomas, was “the road to Ubar … a great city, our fathers have told us, that existed of old, a city rich in treasure … it now lies buried beneath the sands.”

Thomas marked the position of the ancient road on his map, intending to return but never did.

Archaeologist-turned-soldier T. E. Lawrence — known to the world as Lawrence of Arabia, who helped to foment the Arab revolt in the Hejaz during the First World War — made plans to search, by airship, for this “Atlantis of the Sands,” as he called it. However, he died in 1935 in England as a result of a motorcycle crash before he could act on them.

Philby was likewise intrigued by the stories of the lost city. He followed the clues left by Thomas, and directions from his own Bedouin guides, to a place they called Wabar — but which, confusingly at first, was also known to them as Al-Hadida, or “the place of iron.”

Initially, Philby — who had been granted permission to mount his expedition by King Abdulaziz, to whom he had become a trusted adviser — was convinced he had found the ancient city he sought, which was said to have been established by the legendary King Shaddad ibn ‘Ad.

“I had my first glimpse of Wabar — a thin low line of ruins riding upon a wave of the yellow sands,” he wrote in his 1933 book “The Empty Quarter.”

“Leaving my companions to pitch the tents and get our meal ready against sunset, I walked up to the crest of a low mound of the ridge to survey the general scene before dark … I reached the summit and, in that moment, fathomed the legend of Wabar.

“I looked down not upon the ruins of an ancient city but into the mouth of a volcano, whose twin craters, half filled with drifted sand, lay side by side surrounded by slag and lava outpoured from the bowels of the Earth … I knew not whether to laugh or cry, but I was strangely fascinated by a scene that had shattered the dreams of years.”

His guides, still convinced they had discovered the cursed ancient city, dug in the sand for treasure and “came running up to me with lumps of slag and tiny fragments of rusted iron and small shining black pellets, which they took to be the pearls of ‘Ad’s ladies, blackened in the conflagration that had consumed them with their lord.”

In fact, the “pearls” were impactites: Small, black, glass beads created by the heat of the burning meteorite when it crashed into the sand.

Gazing around to take in further evidence of the twin craters and their glass walls, and the scattered fragments of alien metal, it finally dawned on Philby that this was no volcano, nor a lost city, but the site of a huge meteorite impact.

“This may indeed be Wabar of which the badawin speak,” a disappointed Philby told his guides, “but it is the work of God, not man.”

Philby sent a fragment of metal from the site to the British Museum for analysis. It was found to be an alloy of iron and nickel, which is commonly found in meteorites. The museum report concluded that “the kinetic energy of a large mass of iron traveling at a high velocity was suddenly transformed into heat, vaporizing a large part of the meteorite and some of the earth’s crust, so producing a violent gaseous explosion, which formed the crater and backfired the remnants of the meteorite.

Remains of the meteorite on display. (Archives, Getty Images)

“The materials collected at the Wabar crater afford the clearest evidence that very high temperatures prevailed: The desert sand was not only melted, yielding a silica-glass, but also boiled and vaporized. The meteoritic iron was also in large part vaporized, afterward condensing as a fine drizzle.”

Others would follow in Philby’s footsteps. In 1937 the first of several expeditions by geologists from Aramco visited the site. They were disappointed not to find a lump of iron that local rumors suggested was the size of a camel.

In time, however, this “camel” would be found, uncovered by winds that blew away the sand that had buried it. In 1966, an Aramco team found the largest of two exposed pieces of the meteorite, which weighed more than 2,000 kilograms.

It was taken to Aramco headquarters in Dhahran and later put on display at King Saud University in Riyadh. Today, it can be seen at the National Museum of Saudi Arabia in the capital.

As for the lost city of Ubar, the best candidate that has emerged to date is not in the Empty Quarter but about 500 kilometers farther south, near the remote village of Shisr in Oman’s Dhofar province.

The site was identified through analysis of radar imagery collected by the space shuttle Endeavor in 1992, followed by a ground expedition led by British explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, whose book, “Atlantis of The Sands,” is an account of his 24-year search for the lost city.

As NASA reported in 1999, “archaeologists believe Ubar existed from about 2800 B.C. to about 300 A.D. and was a remote desert outpost where caravans were assembled for the transport of frankincense across the desert.”

Disappointingly for lovers of romantic legend, it seems Ubar was destroyed not by the wrath of God but by bad planning. Archaeologists who investigated the site in 1992 believe the city was built over a large cavern and abandoned when it eventually collapsed into a massive sinkhole.