PARIS: The mysterious Fatma Haddad – known by her artist name Baya – rose to fame aged just 16. She was elevated to the rank of icon by a generation of post-war French intellectuals. More than 20 years after her death in 1998, she continues to be venerated by critics and collectors alike.

A new exhibition at the Institut du monde Arabe in Paris, with works donated by Claude and France Lemand, presents a selection of her drawings, gouache paintings and sculptures in a comprehensive tribute to Baya’s career, which spanned more than five decades. Many of the masterpieces on display in “Baya: Women in Their Garden,” which runs until March 2023, come from archives left by the artist’s adoptive mother, Marguerite Caminat.

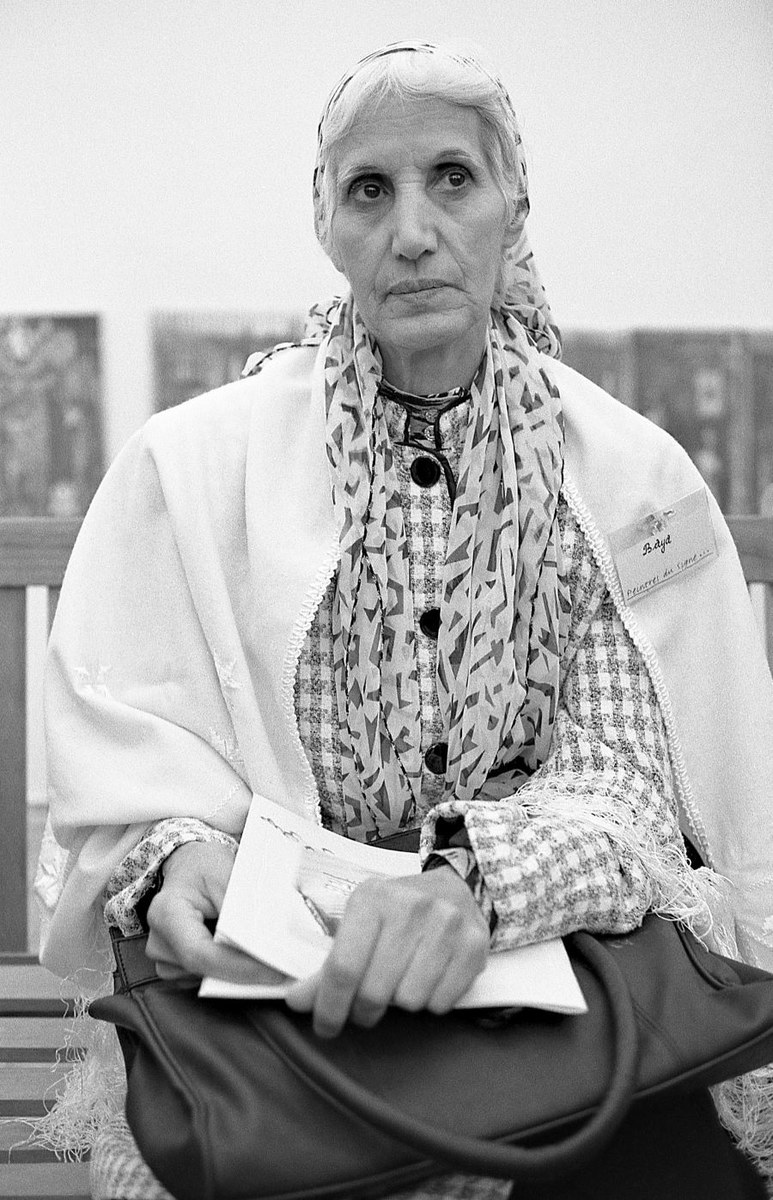

Baya at an exhibition of Algerian artists in September 1998. (A.O. Mohand-min)

Caminat was the first and greatest supporter of Baya’s exceptional artistic talent, which was noted by Parisian gallery owner Aimé Maeght on a trip to Algiers. Maeght invited the 16-year-old to contribute to a major exhibition in Paris in November 1947, where her work dazzled art lovers in the French capital, including André Breton, who wrote: “I speak not like so many others to lament an end, but to promote a beginning. The beginning of an age of emancipation and harmony, in radical rupture … And, of this beginning, Baya is queen.”

“Baya was a gifted artist and a hard worker,” Claude Lemand, one of the exhibition’s curators, told Arab News. “She affirmed her personality, her identity, her autonomy, her decision to (be an artist) at a very young age, but without ever offending others.”

BAYA, 'Lady and Birds in Blue,' 1993. (Alberto Ricci-min)

In 1953, Baya married musician El Hadj Mahfoud Mahieddine and took a 10-year break to devote herself to her family in their home in Blida, Algeria. When she started producing art again, new perspectives were revealed, no doubt influenced by the Algerian War of Independence, which had taken place in the interim.

It was a pivotal period for the artist. “From 1963, she developed new themes, starting with her landscapes — her Garden of Eden — a joyful celebration of nature and life … surrounded by sunny mountains and dunes, with four rivers, the symbolic trees of Algeria — the olive tree and the date palm, and full of birds and fish of all colors. The birds sing, the fish dance,” Lemand said. “Oasis or island, the Garden of Eden has the colors of Algeria: the blue of the Mediterranean, the red of its land, the green of its vegetation, the gold of its dunes.”

Some critics highlighted the repetitive nature of Baya’s work, and in response, Lemand explained, she developed other themes, including her “living stills,” which often incorporated musical instruments, inspired by her husband’s profession.

“All the elements of her (still life works) are represented as living beings, their eyes always wide open to others and to the world, with expressive attitudes of seduction and mutual affection, participating in general harmony, in a symphony of forms and colors,” Lemand added.

From 1963 onwards, Baya developed a third theme: women: “Musicians, dancers, mothers, women alone in their garden or in groups, blooming and happy, standing or sitting, surrounded by musical instruments and birds with which they converse,” Lemand said.

Visitors to the exhibition will see the power of Baya’s joyful, vibrant paintings alongside the elegance of her clay sculptures.

“Baya favors turquoise blue, Indian pink, emerald and deep purple. She paints with unparalleled finesse the world of childhood and motherhood, expressing her fascination for the memory of her mother,” Lemand said. “She drew first in pencil, then she put the color. She started with the women and then moved on to other elements, leaving blanks in her early works, before giving in to the ‘horror of the void’ of the Arab-Muslim aesthetic and filling with motifs all the spaces left empty in her compositions.”

In her paintings, there is harmony between women and all living beings: “Each has their own language, which is understood by all the actors on the scene,” Lemand observed.

Far from the naive image that some have of her work, Baya appears here as an empress of a lush kingdom where young women could freely put their dreams down on paper. As Breton wrote, Baya was the “Queen of happy Arabia.”