RIYADH: Visitors to Wadi Hanifa, an expansive valley in Riyadh lined with palm trees and streams of water, were greeted last weekend by a number of new, large-scale contemporary works of public art created by Saudi and international artists.

The installations are part of Noor Riyadh, an annual festival of light and art featuring more than 190 works by about 130 Saudi and international artists from 40 countries. They are on display until Nov. 19 at 40 locations in five main hubs across Riyadh.

Children played soccer in front of “One Thousand Galaxies of Light,” a work by American/Puerto Rican artist Gisela Colon, which consists of an elliptical configuration of 100 upright white light tubes, each of them is 2.5 meters tall.

Children play in front of ‘One Thousand Galaxies of Light,’ a work by American/Puerto Rican artist Gisela Colon, which consists of an elliptical configuration of 100 upright white light tubes, each of them is 2.5 meters tall. (Supplied)

Colon, who also participated in the first edition of Desert X AlUla in 2020, said she drew on physics, cosmology and biology for this work, which imagines a forest of mythical horizons metaphorically pointing toward a vibrant future, in line with the theme of Noor Riyadh this year: “We Dream of New Horizons.”

At a nearby major thoroughfare, passersby can see Riyadh-based choreographer, dancer and artist Sarah Brahim’s installation, “De Anima,” featuring images projected on the underside of a bridge in the Wadi Hanifa wetlands.

“In this work I was inspired by the way that light permeates through the body and back out again in various ways,” Brahim told Arab News.

Ahaad Alamoudi’s work ‘Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow’ is a performative installation that considers the role of light as a natural carrier of information. It is comprised of two ancient pigeon towers, alluding to the historical use of pigeons as message bearers. (Supplied)

“The work is re-theorizing Aristotle’s text ‘De Anima’ and is looking at five different souls during five different times of the day, about how light animates the soul and the essence of life. Each person represents a physical and metaphorical type of light.”

Brahim also emphasizes the use of time in her piece. Visitors to the installation are offered headphones through which they can listen to a soundtrack as they view the images.

Another work on display at Wadi Hanifah is Saudi multimedia artist Ahaad Alamoudi’s “Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow,” a performative installation that considers the role of light as a natural carrier of information. It is comprised of two ancient pigeon towers, alluding to the historical use of pigeons as message bearers, and a singer who performs a mawwal, a type of traditional Arab song, while light shines out from the openings in each tower.

Noor Riyadh is the first program implemented under the auspices of Riyadh Art. (Supplied)

“The meaning of light is very accessible and appropriate to a city like Riyadh,” Miguel Blanco-Carrasco, the executive director of Noor Riyadh, told Arab News. “The city comes to life after the sunset because of the temperature and the geography of Riyadh.”

In the evening, many residents often go out to dinner or spend time in the city’s many parks. As a result, the festival was devised with the aim of installing art in some of the places in Riyadh where the people are were most likely to see it.

“Light is an accessible medium to everyone, regardless of their educational levels or class or understanding of contemporary art,” said Blanco-Carrasco. “We want to take art everywhere and we want to make it accessible to everyone.”

At a nearby major thoroughfare, passersby can see Riyadh-based choreographer, dancer and artist Sarah Brahim’s installation, ‘De Anima,’ featuring images projected on the underside of a bridge in the Wadi Hanifa wetlands. (Supplied)

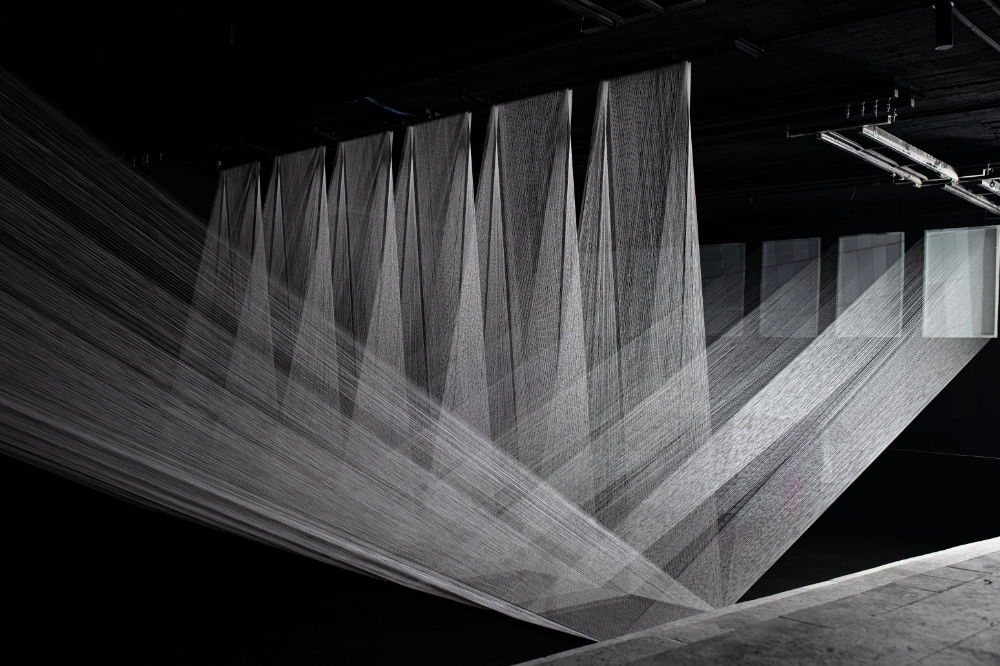

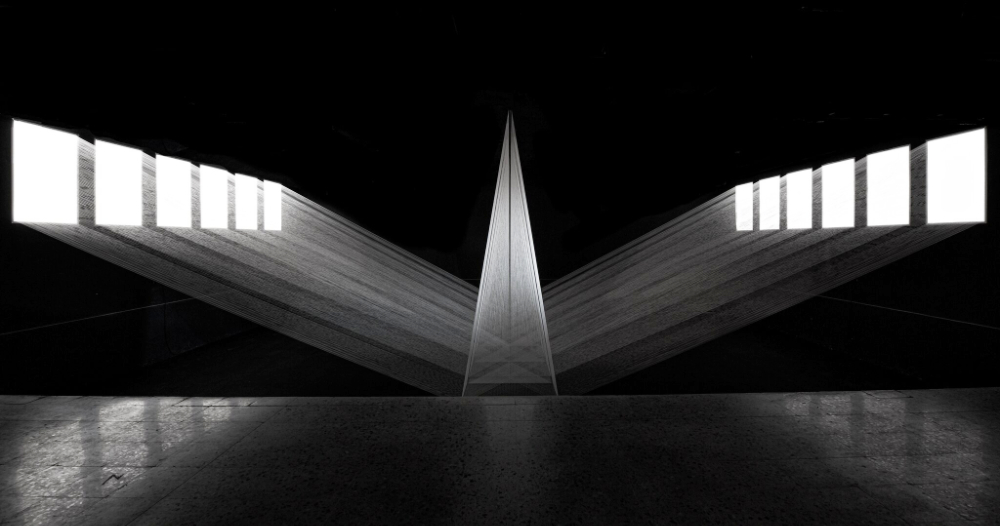

Another highlight of Noor Riyadh is Saudi artist Muhannad Shono’s “I See You Brightest in the Dark,” which is on show in Bayt Al-Malaz.

Saudi-Palestinian artist Ayman Yossri Daydban’s “If God Willing, All Will be Resolved,” meanwhile, uses carefully chosen stills from subtitled movies to create a work that paints Arabic script with light.

It takes its inspiration from the commonly used Arabic phrase, “Inshallah,” meaning “God willing,” which is rendered in large, neon white text on the structure of the derelict Irqah Hospital. It overlooks the abandoned urban landscape around it, breathing new life into a space now largely devoid of human presence.

Noor Riyadh is the first program implemented under the auspices of Riyadh Art. (Supplied)

“Carving the Future,” by Saudi artist Obaid Al-Safi, is presented in a desert landscape. With the work, the artist is questioning the relationship between the desert and the civilization that emerged from it, pondering the links between the Kingdom’s ancient past and its more recent transformations.

Saudi artist Ayman Zedani’s poignant “Between Biotic and Bionic,” in Riyadh’s Olaya district, explores how, in cities across the Gulf region, nature is increasingly something people experience as simulacra, or imitations, such as artificial rainforests or neon jungles, blurring the distinction between what is real and that which is artificial.

It brings together, in Zedani’s signature style, elements of light, sound, sculpture and nature in structures made from welded metal that are covered in resurrection plants, which are types of plants that can survive periods of extreme dehydration, in a nod to the desert landscape and the effects of climate change.

A text work by Joel Andrianomearisoa, an artist from Madagascar, is unmissable. Installed in King Abdullah Financial District and created using neon lights and metal, it relays the message, “On a Never-Ending Horizon, a Future Nostalgia to Keep the Present Alive,” which speaks of love, hope and dreams for the future.

Noor Riyadh is the first program implemented under the auspices of Riyadh Art, the first public art initiative in the Kingdom. It aims to transform the city into a “gallery without walls,” to beautify it and enhance the creative spirit among the population.

One of its objectives, Blanco-Carrasco said, is to “remove any preconceived ideas of contemporary art as accessible only to the elites; we want to make it available to everyone in Riyadh. Noor Riyadh is their festival.”