JEDDAH: Although the majority of Saudi Arabia’s terrain is covered by desert, a surprisingly large number of indigenous plant species are able to withstand the harsh climate. Now, under the umbrella of the Saudi Green Initiative, efforts are underway to preserve, and even increase, the amount of vegetation across the Kingdom.

From its desert vistas in the north to the southern region of Asir, the Kingdom is home to an abundance of vegetation, including more than 2,000 wild plant species belonging to 142 families. According to the Saudi National Center for Wildlife, however, about 600 of thee species are classified as endangered and 21 are already thought to be extinct.

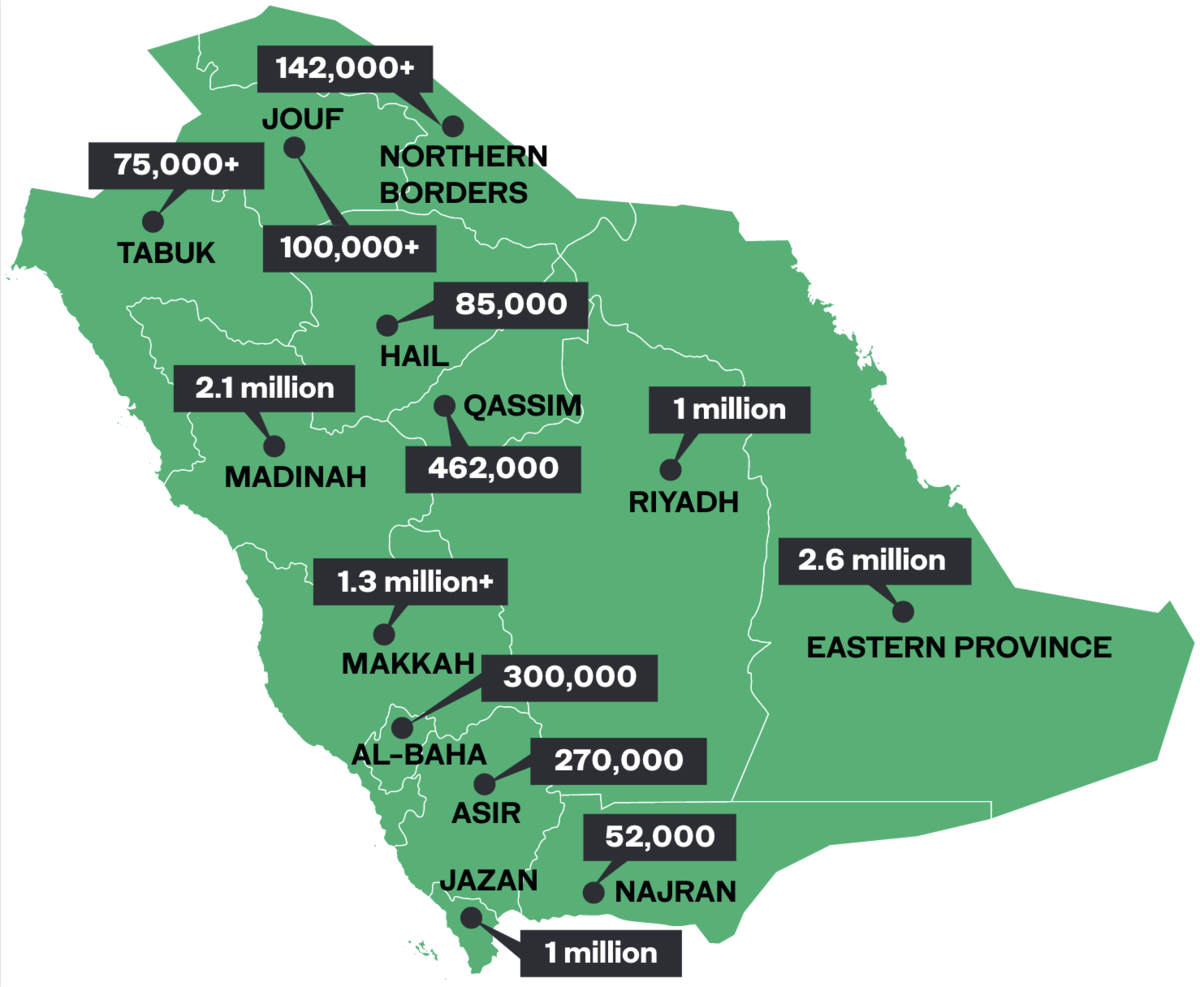

The SGI, announced in March 2021, is the largest afforestation project the country has ever seen, with a target of planting 450 million trees by 2030. By the end of 2021, about 10 million trees had already been planted across all of the Kingdom’s 13 regions.

When one thinks of Saudi Arabia, forests might not be the first type of ecosystem that springs to mind. However, the Kingdom has about 2.7 million hectares of woodland, primarily in the remote southwestern highlands of Abha and Asir.

On the face of it, the goal of planting 450 million trees may sound ambitious, to say nothing of the planned greening of the desert, especially given the frenetic urban expansion the Kingdom is witnessing.

But in fact, to counter the potential harm of urban sprawl, the Saudi government has set specific SGI goals to incorporate green spaces harmoniously into urban expansion, including parkland and afforestation within the limits of the Kingdom’s desert cities.

Wild plants, such as the blood lily, contribute to protection of Saudi Arabia’s unique biodiversity. (Supplied)

The greening of unmanaged surfaces within these cities will not only help to curb rising temperatures but also cut carbon dioxide emissions, improve air quality, provide opportunities for more active lifestyles, and beautify cities in a sustainable way.

In more rural climes, meanwhile, the greening efforts have to work against encroaching desertification, limited water resources and record-high temperatures, all of which are thought to be the result of climate change caused by humans.

The SGI road map sets out to halt and reverse desertification and soil degradation, preserve the Kingdom’s unique biodiversity, and maintain limited water resources in a nation where rainfall in scarce and groundwater is being depleted.

Currently, Saudi Arabia has 15 areas that are protected because of their biodiversity; 12 are on land and three of them are marine. The National Center for Wildlife proposes to increase that number to 75, 62 on land and 13 in coastal and marine areas.

The King Salman Royal Nature Reserve in northern Saudi Arabia covers about 6 percent of the Kingdom’s landmass. It includes mountain terrain, vast plains and high plateaus, and is home to about 300 animal species along with rare archaeological heritage sites, some dating back as far as 8,000 BC.

The reserve’s management has recently planted 100,000 seedings with the help and participation of volunteers in partnership with Maaden, a joint effort by the reserve’s authority and partners to contribute to SGI’s goals.

FASTFACTS

* 2,000 wild plant species are native to Saudi Arabia, belonging to 142 families. However, about 600 are classified as endangered and 21 are already extinct.

* 15 areas are protected in the Kingdom because of their biodiversity, 12 on land and 3 marine. The National Center for Wildlife plans to increase the number to 75.

“We are committed to increasing the vegetation cover, as we have already achieved in planting 600,000 plants as well as having many seed-sowing campaigns to increase the vegetation in the reserve,” a KSRNR spokesperson told Arab News.

“The trees and shrubs are perennial plants that restore the desert-degraded habitats. These plants are native species to the desert habitats and are adapted to the desert’s harsh conditions, such as drought and high temperatures, and do not require excessive water for irrigation.

“The reserve’s strategic objective is to establish a seedling program that includes many projects, such as installing the main nursery.”

Nevertheless, water remains a major challenge for conservation work and greening schemes in the Kingdom. Over the centuries, inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula found ways to sustain life and survive droughts by digging freshwater wells. Over time, and in the wake of the Kingdom’s economic boom in the 1970s, Saudis turned to modern farming methods, increasingly tapping groundwater reserves.

Saudi Arabia and its journey to 10 billion trees - SGI is aiming to contribute to the largest afforestation project in the world.

With no rivers or natural lakes, and very little annual rainfall to replenish sources, Saudi Arabia established seawater desalination plants in its eastern and western coastal areas to support inland cities. Nevertheless, the demand for freshwater is growing and natural aquifers are fast depleting.

The Saudi government is therefore exploring ways to preserve its water resources and use them more efficiently so that they can continue to meet the demands of a growing economy while also keeping green spaces well watered.

Maria Nava, a scientific consultant for Greening Arabia at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Center for Desert Agriculture, told Arab News that the SGI’s strategic team is likely to tap into treated wastewater to irrigate newly planted vegetation.

Another goal, she said, is “to reduce rainfall loss to the sea or through sand infiltration by the implementation and improvement of water harvesting in the Kingdom and remediation of soil for water retention where needed.”

Plants in urban areas tend to need much more water and canopy cover to provide shade than those growing in mountain, wadi and desert climates, Nava said.

“This vegetation requires more water compared with desert trees, which are drought-resistant and have fewer leaves,” she added.

Under the Saudi Green Initiative, efforts are underway to preserve and increase plant life as well as tree cover across the Kingdom. (Supplied)

Given the Kingdom’s diverse topography, much will need to be done to restore arid or semi-arid lands, prevent soil erosion, retain water, farm using permaculture techniques, and plant vegetation that is tolerant of local conditions, including the growing threat of dust storms.

“All areas in the Kingdom are important and are treated as such,” said Nava. “Each action zone has been deeply studied and analyzed for its potential for tree growth, water availability and aftercare of the vegetation.

“Within the scope of each zone, the propositions are based on being sustainable and that the vegetation can be kept and enhanced in the future. It is not that some have more attention than others; it is more that some, because of weather, water availability, soil, topography, etc., have a higher potential to ‘host’ vegetation than others.

“Nevertheless, all ecosystem changes will affect others, which has also been considered. Each strategy has been thought out in order to be sustainable.”

Driven by necessity, Saudi Arabia is rethinking its water-conservation strategy. Given the ambitious goals of the SGI, a shift from irrigation with desalinated water to the use of treated water was recommended because of the energy demands.

A bitter apple. (Shutterstock)

“Desalination is more energy-intensive than wastewater treatment,” said Nava. “It is possible to reuse all the wastewater for irrigation since the water quality is good for it and there are already plans for this to happen in the Kingdom.

“Currently there is already some reuse of treated wastewater, and as part of the national water strategy the reuse of treated wastewater will reach 70 percent by 2030, with plans to increase this percentage in the near future.”

As the nation becomes more aware of its natural bounties, communities across the Kingdom are also beginning to more actively participate in efforts to achieve the goals of the SGI and achieve a greener future.

“The communities are the base for all the initiatives to become real and succeed,” said Nava. “It is highly important to engage and involve the people, hear their needs, understand their traditions and make them part of the decisions.

“The implementation of the SGI has to be based on three main pillars: social, economic and sustainable.”