DUBAI: Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have been praised by the World Food Programme’s regional representative for contributions “that have saved lives and continue to save lives, by making possible the distribution of nutritious food to children, mothers, lactating mothers and expectant mothers.”

Appearing on “Frankly Speaking,” Arab News’ weekly current affairs talk show, Mageed Yahia, WFP representative to the GCC region, cited war-torn Yemen as an example where Saudi Arabia and the UAE “came together to rescue our programs” in 2018 and prevent starvation.

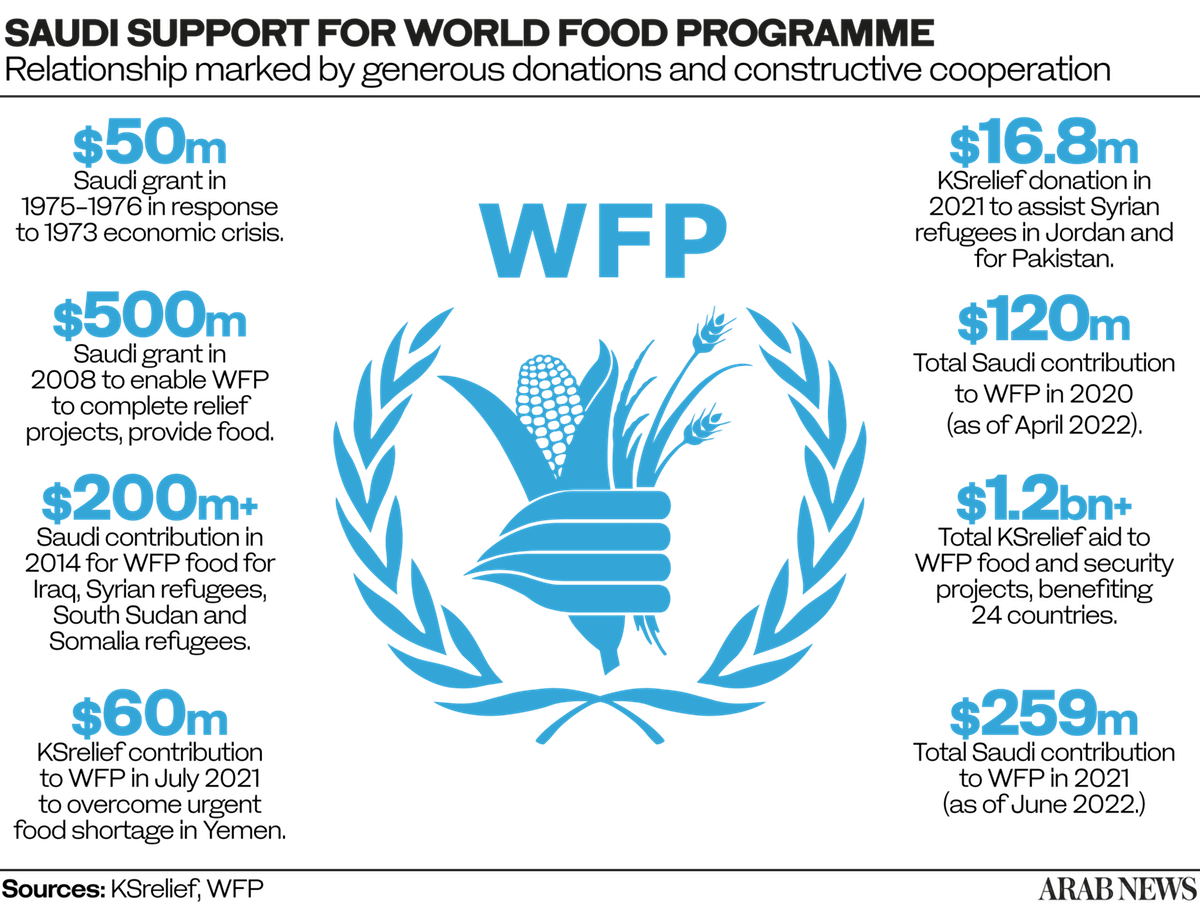

“The biggest impact of that contribution, which was ($1) billion to the UN agencies operating in Yemen, was averting famine. And that was really impactful in that since then the contribution from the Saudis has continued, and continues until now. Again, the impact of that is saving lives.”

Yahia’s comments appear to contradict those made by WFP Executive Director David Beasley during his recent visit to Iceland, where he publicly scolded the Gulf states and China for “not stepping up” in the fight against the global food crisis.

‘Reaching zero hunger by 2030 is possible,’ says WFP regional representative Mageed Yahia, ‘if all the world pulls together.’ (AN Photo)

Claiming that the “Gulf states with massive oil profits right now” are “not stepping up,” Beasley was quoted by the UN’s official website as telling Icelandic TV: “Iceland is not a big country but it is punching above its weight. It is a great role model for other countries to follow.”

Beasley’s characterization of the two Gulf countries also flies in the face of the WFP’s own summary of 2021 global contributions (as of June 21, 2022), which show Saudi Arabia and the UAE as the seventh and 12th biggest donors, respectively. In fact, on a per capita basis, the two states come out as the WFP’s top two donors globally.

As recently as November last year, the WFP welcomed “a timely and generous contribution” of $16.8 million from Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center (KSrelief) to assist Syrian refugees in Jordan and to support nutrition programs for women and children in Pakistan.

The Saudi contribution was made as the WFP struggled to secure funds to continue support to some 465,000 vulnerable refugees in Jordan — most of them from Syria — and assist more than 66,000 of the most vulnerable children and women in Pakistan.

Yahia acknowledged the manifold benefits of Gulf aid to Yemen through the WFP. “The impact of that is that we’re keeping people alive there,” he said.

“The Saudi contribution helps us, of course, in this life-saving agenda, but also in the nutrition agenda when giving specialized nutritious food to children, to mothers, lactating mothers and pregnant mothers. Because if you don’t do that today, tomorrow you will have a negative effect of that, (in terms of) school-feeding that we are providing.

He added: “We are providing school meals both in the north and in the south. And that’s a development activity that we’re doing. It is important what the Saudis and the Emiratis are doing with us in Yemen to help keep people alive, saving their lives and (allowing the continuation of education).

“This is something very important for the children there.”

Asked how many lives have possibly felt the impact of the joint Saudi-UAE aid support, Yahia said: “We’re talking about 40 million people in Yemen. That’s maybe half of the population, or more than half of the population.”

Global food prices rose rapidly earlier this year as the war in Ukraine disrupted the supply and distribution of grain and fertilizer. This followed hot on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, which had exposed the vulnerability of global supply chains.

As a result, many observers have concluded that it is highly unlikely the UN will achieve its Sustainable Development Goal of eliminating hunger by the end of the decade. Yahia still holds out hope.

“The good news first is that reaching zero hunger in 2030 is possible. It’s something doable if all the world comes together. If there is the political will, we can do it. But we have been going in reverse for the last five years,” he said.

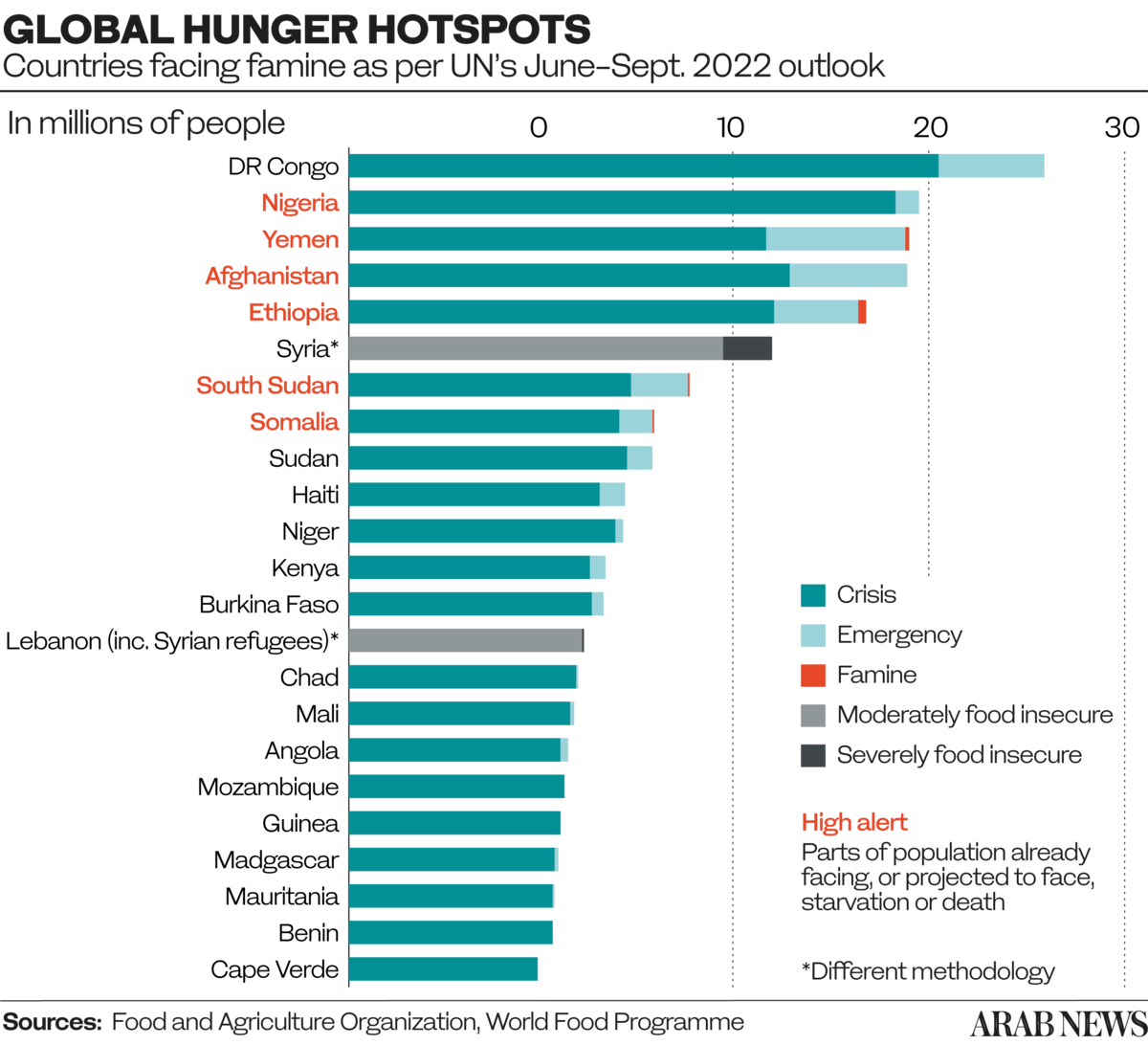

“We saw good progress in 2015 when the number of hungry people decreased, but then it started to increase. Conflict is the main driver of hunger around the world. Now we see it in Yemen, we see it in Syria, in Afghanistan, in South Sudan and in the Sahel.

“Second is the climate. Food production, to a large extent, depends on climate. So if there is any change there, then food production is a problem. You have the situation now in the Horn of Africa, where in Somalia around 3 to 4 million people are displaced because of drought.”

Contributions by Gulf states were praised by World Food Programme regional representative for averting famine, and safeguarding children and mothers in Yemen. (AN Photo)

Yahia took pains to explain a conundrum of the global food crisis: “In many cases, hunger is not the result of scarcity but rather a matter of affordability. Food is available everywhere. The world produces more than is consumed. But some communities, 800 million people, cannot afford this food.”

According to the regional director, in countries of the Middle East and North Africa that are largely reliant on imports of food and fertilizers — particularly in such crisis-hit nations as Lebanon, Syria and Yemen — the spiraling cost of these commodities has increased rates of hunger and malnutrition.

“You look at the currency devaluation in Lebanon. It’s huge. You look at inflation — food price inflation there is huge,” Yahia said. “Lebanon in itself depends to a large extent on food imports. At the same time, Lebanon is a host to 1 million Syrian refugees. So all these things are coming together.”

In the case of Yemen, the distribution of aid is also routinely disrupted by the Iran-backed Houthi militia, which controls swathes of the country, including the capital, Sanaa. Yahia says that gaining access to vulnerable populations is half the battle.

“Like in any conflict, one of the major issues that we face when we work in conflict areas is access to the population,” he said. “And that, of course, takes maybe 50 percent of our efforts to negotiate access to this population.

“Second is the number of people that depend on our food assistance. And now because of funding, because of prolonged conflict, we are taking really tough decisions in Yemen by reducing our rations.”

He warned that the reduction in the amount of food the WFP is able to distribute in Yemen is also the result of a decline in the amount of financial assistance provided by donor countries, combined with the sheer scale of need in multiple crisis zones across the globe.

With multiple overlapping crises blighting vast areas of the developing world, WFP is short of the funding required to support existing projects Yahia told Katie Jensen on Frankly Speaking. (AN Photo)

“It’s mainly due to the protracted nature of the crisis, but also of crises coming up in different parts of the world that may be competing with the situation in Yemen,” Yahia said. “But, at the end of the day, we need to keep Yemen, Syria, South Sudan, all these places in the headlines so that people do not forget about the situation there.”

One way the WFP aims to address supply chain disruptions, mitigate shortages of funding, and improve the accessibility and affordability of food is to encourage production closer to the point of need.

“You have 80 percent of the food in Africa produced by smallholder farmers, but unfortunately some of them end up as beneficiaries of our assistance,” he said. “Why? Because of losses that they make, because they don’t have access to markets. There is no logistics supply chain and storage facilities are not adequate. So more than half of their harvest is lost.”

In order to support local farmers, the WFP counts on donor countries. However, according to Yahia, with multiple overlapping crises blighting vast swathes of the developing world, the agency is short of the funding required to support existing projects.

“We need an additional $9 billion because our projection for 2022 alone is $24 billion,” he said. “So far we have raised around $9 billion. We know we will not be able to reach our projected requirements, but if we don’t get it, then next year, with the availability crisis looming, we will need more than that.

Yahia added: “In the short term, you need to help these communities. You need to save their lives. Unfortunately, because of the conflicts, because of climate, which is a real threat to full food security because of the economy, this number continues to grow.”