LONDON: Since the death of Mahsa Amini after being taken into custody by Iran’s notorious morality police, protests have raged in cities across the Islamic Republic, beginning in Amini’s home province of Kurdistan.

Amini, a 22-year-old ethnic Kurdish woman, died on Sept. 16, three days after she was arrested in Tehran by the Gasht-e Ershad, the regime’s vice squad, which enforces strict rules on women’s dress, including the hijab.

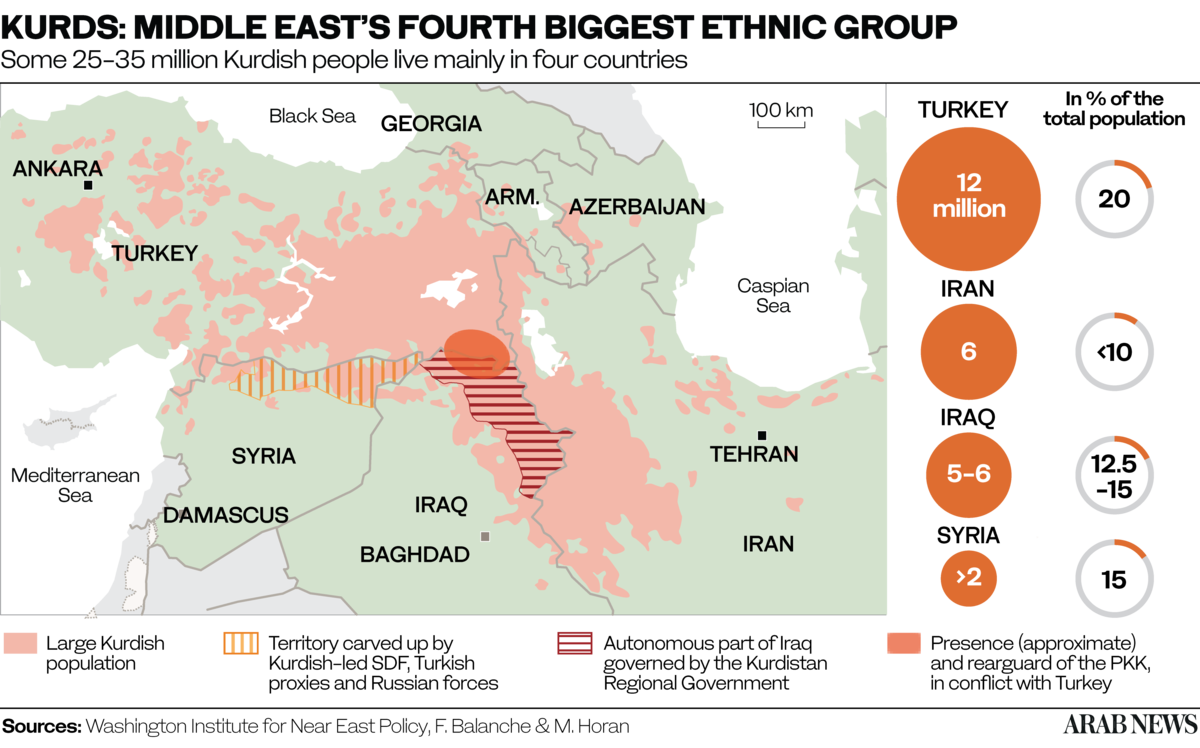

Her death has highlighted the oppression and marginalization of women in Iran. It has also cast a light on the ill-treatment of the country’s non-Persian ethnic minorities, particularly its substantial Kurdish population, concentrated in the west of the country.

In turn, this has highlighted the contrasting treatment of women in other areas of the Middle East in which Kurds make up a majority of the local population — in northern Iraq, southeast Turkey and northern Syria — where women are prominent in both civic and military life.

On Sept. 24, a protest was held in solidarity with the women of Iran outside the UN compound in Irbil, capital of the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region of Iraq. Many of those who took part were Iranian Kurds living in self-imposed exile in a city known for its culture of tolerance.

Kurdish opposition groups have consistently fought for an alternative vision for society. (AFP)

Bearing placards with Amini’s face, the protesters chanted “women, life, freedom,” and “death to the dictator,” in reference to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

“They killed (Amini) because of a piece of hair coming out from her hijab. The youth are asking for freedom. They are asking for rights for all the people because everyone has the right to have dignity and freedom,” one protester Namam Ismaili, an Iranian Kurd from Sardasht, a Kurdish town in Iran’s northwest, told Reuters.

“We are not against religion, and we are not against Islam. We are secularists, and we want religion to be separate from politics,” Maysoon Majidi, a Kurdish Iranian actor and director living in Irbil, told the news agency.

Last week, Masoud Barzani, president of Iraqi Kurdistan’s governing party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party, called Amini’s family to express his condolences, saying he hoped justice would be served.

Last week, Masoud Barzani, president of Iraqi Kurdistan’s governing party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party, called Amini’s family to express his condolences, saying he hoped justice would be served.

Kurdish political identity throughout the region and among the community’s large European diaspora embraces secularist, nationalist and even socialist traditions. In the case of Iran’s Kurds, this frequently puts them at odds with the country’s theocratic regime.

On Sept. 23, the Kurdish-majority town of Oshnavieh in Iran’s West Azerbaijan province briefly fell into the hands of protesters, who set fire to government offices, banks, and a base belonging to the regime’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Amini’s death has highlighted the oppression and marginalization of women in Iran. (AFP)

In response, the IRGC shelled the offices of Iranian Kurdish opposition groups based in Sidakan in Iraq, accusing the Kurdish parties of inciting “chaos.”

Tasnim news agency, which is affiliated with the IRGC, said the shelling targeted the offices of Komala and the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran for allegedly sending “armed teams and a large amount of weapons … to the border cities of the country to cause chaos.”

The KDPI is a Kurdish opposition party that has waged an on-and-off armed campaign against the regime since the Islamic Revolution. Komala, meanwhile, is a leftist Kurdish armed opposition party, which fights for the rights of Kurds in Iran.

Although Iran’s constitution grants ethnic minorities equal rights, allowing them to use their own language and practice their own traditions, the Kurds, Ahwazi Arabs, Baloch, and other groups say they are treated as second-class citizens — their resources extracted, their towns starved of investment, and their communities aggressively policed.

Kurdish opposition groups in Iran have fought for decades to obtain greater political and cultural rights for their communities, which are spread across a part of the country known to Kurds as Rojhelat — or Eastern Kurdistan.

This nationalist spirit has often meant women’s emancipation has been viewed as a secondary concern against the overarching fight for Kurdish nationhood, especially in the case of Iraqi Kurdish leaders, who have long drawn their support from traditional tribal structures.

However, elsewhere in the region, Kurdish opposition groups have consistently fought for an alternative vision for society — one that is based on democratic values and on the equal status of women.

Nowhere is this perhaps more obvious than in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), where the political arm of the US-allied Syria Democratic Forces has established a self-governing polity known to Kurds as Rojava — or Western Kurdistan.

On Friday, Mazloum Abdi, commander in chief of the SDF, condemned the killing of Amini, describing it as a “moral failure” of the ruling authorities in Iran.

He also expressed solidarity with the protests in Iran via Twitter, saying: “The Kurdish and women’s issues must be resolved in appropriate ways.”

On Friday, Mazloum Abdi, commander in chief of the SDF, condemned the killing of Amini, describing it as a “moral failure” of the ruling authorities in Iran. (AFP)

In Rojava, Kurdish women fighting in guerrilla brigades against Daesh have achieved iconic status — especially the Women’s Protection Units, or YPJ, the all-women brigades of the People’s Protection Units.

These YPJ fighters won global acclaim in 2014 for their role in the liberation of the Kurdish-majority city of Kobane in northern Syria from an extremist group whose warped interpretation of Islam would have seen them enslaved.

Soon after their victory, images of young, unveiled, mostly Kurdish YPJ fighters appeared on magazine covers and in newspapers around the world, demolishing many prevailing stereotypes in the West about Middle Eastern women as passive victims.

Within the AANES, there are now several women-only organizations, while in the areas of Syria under YPJ control, child marriage has been abolished, the practice of men taking multiple wives outlawed, and domestic abuse treated with the utmost severity.

The focus on women has also led to a policy called the “co-chair” system, whereby all positions of authority are held by both a man and a woman with equal collaborative power. As a result, women in Kurdish areas of Syria hold 50 percent of official positions.

A similar model is employed by the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party in Turkey and among the ranks of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, inspired by the values of its jailed founder Abdullah Ocalan.

Although honor killings and female genital mutilation have remained all too common in parts of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, women’s political participation and leadership has improved greatly in recent years, with the role of speaker in the Kurdistan parliament twice being held by a woman.

Kurds, Ahwazi Arabs, Baloch, and other groups say they are treated as second-class citizens in Iran. (AFP)

In 2018, the Kurdistan Regional Government raised its gender quota in Parliament from 25 percent to 30 percent, so that 34 out of 111 sitting MPs are now women.

The Daesh attack on Yazidi women in Sinjar in Aug. 2014 also encouraged more Kurdish women to join the frontline war effort, challenging their victim role in warfare and broadening their identity from being mere caregivers to protectors.

This brought forward changes in Kurdish society concerning women’s roles and identities, making it easier for women to join the Peshmerga — the armed forces of the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

Despite the region’s recent achievements, Iraqi Kurdish women’s campaigner Sherri Talabany reported during the MERI Forum 2019 that women still face high rates of domestic violence and a low share in the labor market of just 14 percent.

Kurdish opposition groups in Iran have fought for decades to obtain greater political and cultural rights for their communities. (AFP)

Meanwhile, only three representatives in the 23-member Iraqi Cabinet are women, and only one in the KRG cabinet of 21 ministers.

But the picture is far bleaker in Iran, where female labor force participation reached just 17.54 percent in 2019, compared with the global average of 47.70 percent, giving Iran one of the lowest levels of female labor-force participation in the world.

Women in Iran also face restrictions in reaching managerial and decision-making positions in the public and private sectors. In addition, owing to Western sanctions, erratic economic policies and the COVID-19 pandemic, Iran’s economy has shrunk in recent years, affecting women’s employment opportunities.

What the protests sweeping Iran in response to Amini’s death appear to show is a general rejection of the maltreatment of women and ethnic minorities, frustration over the economic situation, and outrage at the heavy-handed ways of the morality police.

What the protests sweeping Iran in response to Amini’s death appear to show is a general rejection of the maltreatment of women and ethnic minorities, frustration over the economic situation, and outrage at the heavy-handed ways of the morality police.

Some Iranians who cross into Iraqi Kurdistan for work or to see relatives have told AFP that while Amini’s death was a trigger, the long-running economic crisis and the climate of repression fed into the explosion of anger.

“The difficult economic situation in Iran … the repression of freedoms, particularly those of women, and the rights of the Iranian people led to an implosion of the situation,” Azad Husseini, an Iranian Kurd who now works as a carpenter in Iraq, told the news agency.

“I don’t think the protests in Iranian cities are going to end anytime soon.”