DUBAI: The explosion that ripped through Beirut Port on August 4, 2020, devastated the Lebanese capital. Two years later, the city has not yet recovered from the damage and deaths caused that day.

The blast wrecked hundreds of heritage buildings located in the city’s historic neighborhoods of Mar Mikhaël and Gemmayzeh, many of which were already in a state of disrepair. The government has shown little interest in repairing them. The buildings that have been restored have relied largely on privately funded initiatives.

One such building is Medawar 479, also known as The Blue House. Situated on Beirut’s waterfront, close to what was the epicenter of the explosion, and previously a restaurant, this charming and significant site was one of the original shoreline’s cluster of more than 25 heritage buildings, many of which were destroyed in the explosion.

The Blue House on August, 7 2020. (Getty)

The Beirut Heritage Initiative was launched in the aftermath of the explosion to act as an independent and inclusive collective for the restoration of the city’s built cultural heritage. The BHI approached The Honor Frost Foundation, a maritime archaeology charity, in 2020 to collaborate on restoring The Blue House. Work began in November 2021.

“We launched BHI a few days after the blast. It was founded by architects, heritage experts, and activists that wanted to fundraise for the heritage buildings, mainly in Beirut, which were affected by the blast,” architect Yasmine Dagher of the BHI told Arab News. “In late 2020 we contacted the Honor Frost Foundation and proposed to them several buildings that used to be on the shoreline to have funding for the renovation of the buildings and HFF selected one out of the two buildings that we proposed.

“The funding for the renovation comes in exchange for the usage of the space for a certain number of years,” she continued.

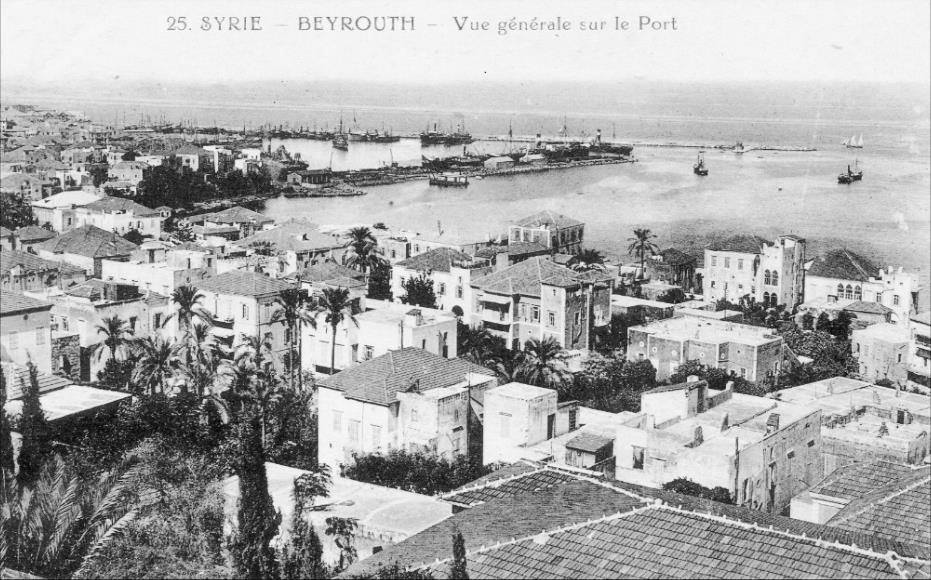

A shot of Beirut Port in 1890 - The Blue House is on the waterfront, second from the left. (Supplied)

The owner of the building is now returning to the top floor of The Blue House, while the Honor Frost Foundation will occupy the first floor, she explained.

The late Honor Frost was an early pioneer of marine archaeology, and had a special connection with Lebanon, so it is fitting that the charity will now have an office in Beirut. The country was a key site of exploration for Frost from 1957 onwards, after she had completed her training under Jacques Cousteau’s diving partner, Frédéric Dumas.

Her work led her to the ancient harbors of Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre, where she researched and documented coastal landscapes, harbor archaeology, site-formation processes, and anchors.

It was at these ancient sites that Frost’s interest in stone anchors began. In Byblos she spotted a series of them built into the Bronze Age temple and discovered similar anchors off the nearby coast, thus improving our knowledge of ancient maritime trade patterns.

Since its launch in 2010, the HFF has invested $3.3m in Lebanese projects, including creating an underwater archaeology course— the first of its kind — at the American University of Beirut, in addition to the granting of scholarships and the Beirut Port Project, a survey of the port area that provides an important overview of the city’s maritime cultural landscape.

Repainting the interiors. (Justine Chalfoun)

“She never thought of herself as a (female pioneer),” chair of HFF trustees, Alison Cathie, told Arab News of Frost. “She simply thought of herself as someone who was doing something for the world.”

And the charity that shares her name is carrying on that work, with the restoration of The Blue House. Once the home of an important merchant, but most recently a restaurant, The Blue House was erected in 1890. It is a fine example of the style of Beirut houses of the late 19th century. Its north façade would once have offered stunning, expansive views out over the Mediterranean Sea.

The restoration work was carried out over the course of a year and included structural consolidation and reconstruction of the pitched roof and the north façade, as well as interior work. Architect-restorer Joe Kallas, supported by Distruct Solutions, Awaida for Construction and Engineering, and Yasmine El-Majzoub from the BHI team led the restoration process, which has actually revealed numerous previously unknown — or perhaps forgotten — features of the building.

Restoration work included the reinstation of a set of previously capped triple arches that formed the principal bay window overlooking the harbor. During the work, it was discovered that the central span had been vaulted and made into a rectangular shape during the 20th century.

Reconstructing the arches. (Yasmine El-Majzoub)

The team have now reinstated the original façade design, reusing materials found on site and employing traditional craft techniques to preserve the identity of the building. Among the highlights of the restoration work are the windows, which have been renovated, and rebuilt where necessary, in Lebanese cedar wood, using historic archives to recreate the original design and murals, which had lain hidden for decades, in delicate blue stenciling. These were uncovered and restored in the central halls on the first and second floors.

The restoration work is now fully complete. The next phase, the BHI team say, involves furnishing the home for occupation in spring 2023.

The Blue House was chosen as a focus for the HFF’s work chiefly for its commanding position on the former shoreline. But it will also provide a fitting office for the charity in Lebanon on completion, an office that will double as both a workspace and occasional exhibition space.

“We have also done a complete assessment of the maritime archaeology at the port of Beirut for Lebanon’s director of antiquities,” Cathie said. “When it comes to rebuilding, they will know what goes where.”

“We hope this restoration project will encourage more people to visit the house and appreciate its heritage,” Dagher added. “Before the blast, heritage buildings were very private; not a lot of people had access to these kinds of buildings. The owner of The Blue House wants people to have awareness of it, and for Lebanon’s heritage to be accessible to citizens and to visitors.”