NEW YORK CITY / BOGOTA, Colombia: Since the Taliban seized Kabul in August 2021, two decades of progress in women’s education, employment, and empowerment in Afghan public life have been dramatically rolled back, leading to calls for the international community to increase pressure on the regime.

Speaking at a recent UN news conference, Naheed Farid, an Afghan women’s rights activist who was the youngest-ever politician elected to the nation’s parliament in 2010, urged world leaders to label the Taliban a “gender apartheid” regime.

Afghan women’s rights activist Naheed Farid speaks at a UN conference on women rights. (Supplied)

“Afghan women are experiencing one of the biggest human rights crises in the world and in the history of human rights. What is happening in Afghanistan is gender apartheid,” Farid told reporters in New York on Sept. 12.

“I’m not the first to say that. But the inaction of the international community and decision-makers at large makes it important for all of us to repeat this every time we can.”

Just as it had in South Africa in the 1980s and ’90s, Farid said the apartheid label could be a catalyst for change in Afghanistan, where severe restrictions have been placed on women’s movements, right to work and access to education since the Taliban took power.

The OIC and other multilateral bodies need to get the Taliban to respect women’s and human rights issues, says advocate Naheed Farid. (Supplied)

When world leaders meet for the UN General Assembly in New York City, Farid said, they must speak with Afghan women living in exile and try to grasp the severity of the situation facing women and girls in Afghanistan.

“All Afghan women, regardless of where they are, feel abandoned by the international community, feel like their voices are not heard, and their demands not reflected in any of the discussions and policies impacting the future of their countries,” she said.

Farid called on the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and other multilateral bodies to create a platform for Afghan women to directly negotiate with the Taliban on women’s rights and human rights issues.

Also speaking at the press conference, Najiba Sanjar, an Afghan feminist and human rights activist, urged governments to maintain sanctions on the Taliban, to ban the group’s representatives from the UN, and for all delegations meeting with regime officials to include women.

“There was a need to engage with the Taliban to protect women’s rights in Afghanistan, but this engagement first must not be behind closed doors with the absence of Afghan women,” said Sanjar.

“Secondly, the engagement with the Taliban should not give legitimacy and recognition to the Taliban. And, as always, and especially this month before the world convenes for the UN General Assembly, we ask that Afghan women are not forgotten, not silenced, and not relinquished as collateral damage of the world’s broken promises.”

According to a new UN report, achieving full gender equality worldwide could be centuries away, with existing disparities compounded in recent times by multiple global crises and a backlash against empowerment of women in some countries.

By the end of 2022, around 383 million women and girls will live in extreme poverty compared to 368 million men and boys, says UN report. (AFP)

In 2015, the UN launched the Sustainable Development Goals — a set of aspirations covering everything from ending hunger to making education available to all — to be achieved by 2030. Among them was the goal of gender equality.

However, according to the UN report, titled “Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2022,” compiled by UN Women and the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, this goal is unlikely to be achieved this century, let alone by the end of the decade.

At the current rate of progress, the report estimates it will take up to 286 years to close gaps in legal protection and remove discriminatory laws, 140 years for women to be represented equally in positions of power and leadership in the workplace, and at least 40 years to achieve equal representation in national parliaments.

To eradicate child marriage by 2030, the report says progress must be 17 times faster than the progress of the last decade. It also points to a reversal in the reduction of poverty and says rising prices are likely to exacerbate this trend.

By the end of 2022, around 383 million women and girls will live in extreme poverty compared to 368 million men and boys. Many more will have insufficient income to meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and adequate shelter in most parts of the world, the report adds.

“This is a tipping point for women’s rights and gender equality as we approach the halfway mark to 2030,” Sima Bahous, UN Women executive director, said in a statement.

“It is critical that we rally now to invest in women and girls to reclaim and accelerate progress. The data show undeniable regressions in their lives made worse by the global crises — in incomes, safety, education, and health. The longer we take to reverse this trend, the more it will cost us all.”

Several overlapping crises have contributed to this reversal in women’s rights and opportunities. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic repercussions have taken a disproportionate toll on women and women-headed households.

In 2020, school and preschool closures during the pandemic required 672 billion hours of additional unpaid childcare globally. Assuming the gender divide in care work remained the same as before the pandemic, women would have shouldered 512 billion of those hours.

Globally, women lost an estimated $800 billion in income in 2020 due to the pandemic, and, despite a rebound, their participation in labor markets is projected to be lower in 2022 than it was pre-pandemic.

At the same time, regional conflicts and the impact of climate change have displaced millions. There are now more women and girls who are forcibly displaced than ever before — some 44 million women and girls by the end of 2021.

Meanwhile, about 38 percent of female-headed households in war-affected areas experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2021, compared to 20 percent of male-headed households, according to the UN report.

The war in Ukraine has only compounded this food insecurity, causing a spike in the market price of bread, cooking oils, and other staples in some of the world’s most vulnerable, import-dependent contexts.

“Cascading global crises are putting the achievement of the SDGs in jeopardy, with the world’s most vulnerable population groups disproportionately impacted, in particular women and girls,” Maria-Francesca Spatolisano, assistant secretary-general for policy coordination and inter-agency affairs at UN/DESA, said in a statement.

“Gender equality is a foundation for achieving all SDGs and it should be at the heart of building back better.”

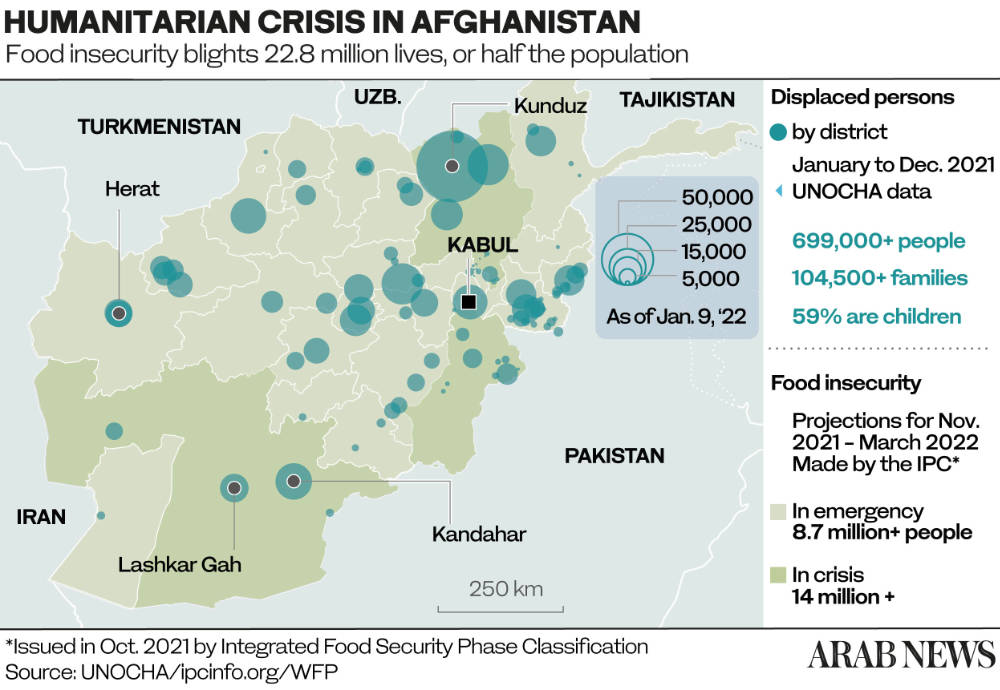

Isolated on the world stage, deprived of essential financial assistance, and afflicted by drought and other natural disasters, Afghanistan is uniquely vulnerable to this amalgam of crises.

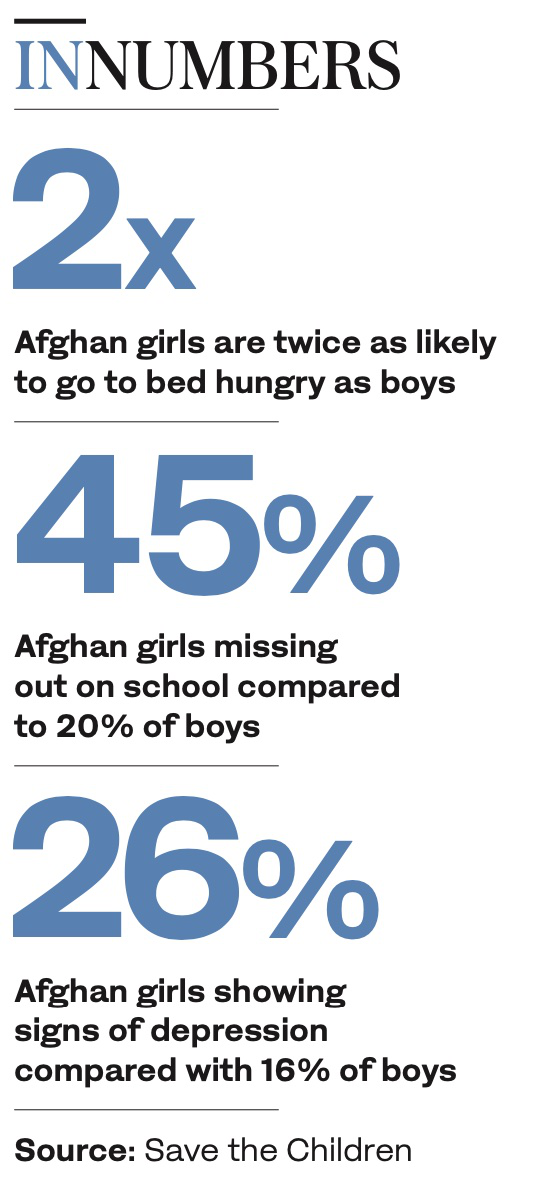

A recent survey of women inside Afghanistan highlighted at the press conference by Sanjar, found that only 4 percent of women reported always having enough food to eat, while a quarter said their income had dropped to zero.

Family violence and femicide have reportedly increased, and 57 percent of Afghan women are married before the age of 19, the survey found. There are even cases of families selling their daughters and their possessions to buy food.

Family violence and femicide have reportedly increased, and 57 percent of Afghan women are married before the age of 19, the survey found. There are even cases of families selling their daughters and their possessions to buy food.

“We are all watching the sufferings of women, girls and minorities from the screens of our TVs as if an action movie is going on,” Sanjar told reporters. “A true form of injustice is taking place right in front of our eyes. And we are all watching silently and partaking in this sin by staying complacent and accepting it as a new normal.”

And the Taliban’s treatment of women could be worsening the situation for Afghanistan as a whole. Unless the Taliban shows it is willing to soften its hardline approach, particularly on matters relating to women’s rights, the regime is unlikely to gain access to billions of dollars in desperately needed aid, loans and frozen assets held by the US, International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Furthermore, keeping women out of work costs Afghanistan up to $1 billion, or 5 percent of gross domestic product, according to the UN.

“It is more important than ever to keep the situation of women in Afghanistan high on our agenda,” said Mona Juul, permanent representative of Norway to the UN, speaking at the Sept. 12 UN press conference, which was organized by the Norwegian mission.

Norway is the penholder on Afghanistan-related issues at the Security Council. The role of penholder refers to the member of the UN body that leads the negotiations and drafting of resolutions on a particular issue.

Juul added: “One year after the Taliban takeover, the situation for women and girls has deteriorated at a shocking scale and speed. Countries, like my own, will continue to engage with the Taliban directly to underscore how girls’ education and women’s participation are fundamental, not least to respond to the dire humanitarian and economic crisis in the country.”

Studies have shown that each additional year of schooling can boost a girl’s earnings as an adult by up to 20 percent with further impacts on poverty reduction, better maternal health, lower child mortality, greater HIV prevention, and reduced violence against women.

“In Afghanistan, like everywhere else in the world, sustainable peace and development can only happen when women fully participate in all aspects of political life,” said Juul. “No country can afford to leave behind their women and girls.”

For millions of Afghan women and girls who had experienced some semblance of freedom under a UN-recognized government from 2001 to 2021, the future under the Taliban appears unfathomably bleak.

“I’m hearing more and more stories from Afghan women choosing to take their life out of hopelessness and despair,” said Farid.

“This is the ultimate indicator on how bad the situation is for Afghan women and girls — that they are choosing death, and that this is preferred for them than living under the Taliban regime.”