DUBAI: Comments recently made by a White House official to Al-Arabiya point to progress in indirect negotiations between Lebanon and Israel to find a solution to their maritime boundary dispute. But any progress raises a host of questions that Hezbollah, the Iran-backed militia which holds sway over the Lebanese government, will find deeply embarrassing.

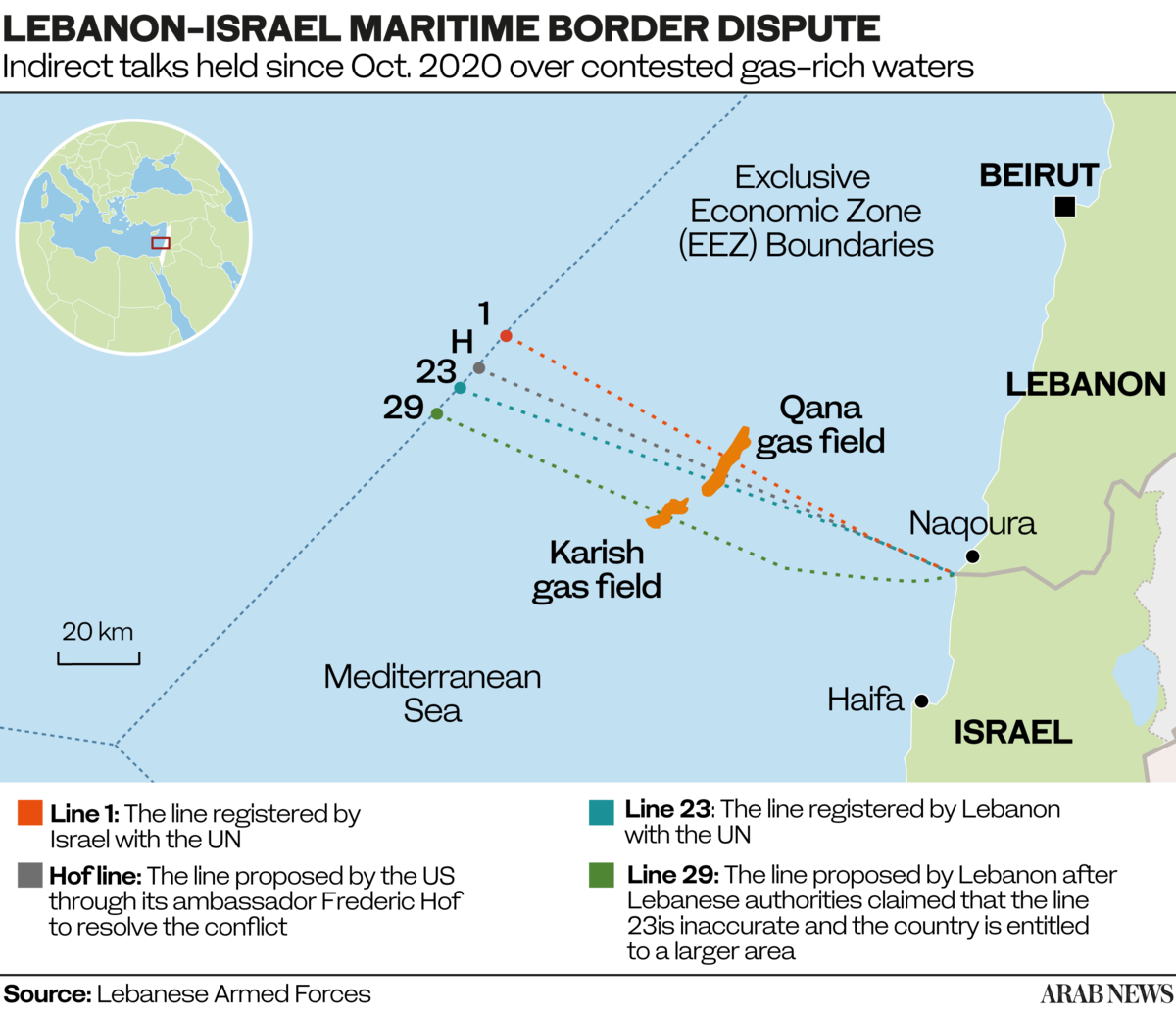

Technically at war since 1948 and with no diplomatic relations, Lebanon and Israel are at odds over an area of 860 sq km of the Mediterranean Sea believed to contain rich deposits of natural gas. They have been engaged in intermittent negotiations since October 2020 over the gas-rich waters they both claim to lie in their exclusive economic zones.

US President Joe Biden’s administration has proposed a compromise solution, which would create an S-shaped maritime economic boundary between the two countries. Amos Hochstein, the US senior adviser for energy security, told Al-Hurra TV in June that a proposal Lebanese officials presented to him will enable negotiations “to go forward.”

In recent months, Hochstein, in his capacity as the special presidential coordinator on the border deal, has made multiple trips to Beirut and Tel Aviv.

“We continue to narrow the gaps between the parties and believe a lasting compromise is possible,” the unnamed White House official told Al-Arabiya this week. The official praised what he called the “consultative spirit” of both parties.

The optimistic assessment came against a backdrop of seemingly coordinated anti-Israel posturing by Lebanese government officials and their coalition ally, Hezbollah. Michel Aoun, the Lebanese president, and his Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) have maintained a strategic alliance with Hezbollah since 2006 that has enabled them to fill public and administrative institutions with loyalists.

Lebanese President Michel Aoun (R) meeting with US special envoy Amos Hochstein (C) and US Ambassador Dorothy Shea in Baabda, east of Beirut, on June 14, 2022. (DALATI AND NOHRA photo via AFP)

The understanding between the leading Lebanese Christian and Shiite parties has been tested at times by Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah’s warlike rhetoric and broadsides against Lebanon’s traditional Arab allies. But with the ongoing negotiations with Israel, Hezbollah’s much vaunted commitment to “resistance,” its political strength and even its relevance have been called into question.

“Hezbollah accuses all its opponents of being Zionist and imperialist agents. So, any occasion to prove it wrong is welcome,” Nadim Shehadi, a Lebanese economist and political commentator, told Arab News. “That said, this is one of the rare instances where the presence of Hezbollah possibly strengthens the Lebanese negotiation position.”

Hezbollah has threatened to attack Israel if a deal acceptable to Lebanon is not reached by a clear deadline. In early July, it dispatched drones twice toward the Karish gas field — where Israel has a drilling site — three of which were shot down by the Israeli military.

Although the drones were unarmed, they demonstrated Hezbollah’s ability to strike the offshore facility and up the ante in the US-mediated negotiations with Israel. In recent months, Israel has also repeatedly accused Hezbollah of impeding UN peacekeepers stationed along the Lebanon-Israel border from performing their duties.

UNIFIL and Lebanese military vehicles on guard at the demarcation of the maritime frontier between the Israel and Lebanon, in the southern Lebanese border town of Naqura. (AFP file photo)

Still, Hezbollah is said to privately want to avoid another conflict at a time Lebanon is going through a crippling economic crisis that has plunged more than three-quarters of its population into poverty. The last war it fought with Israel, 16 years ago, left nearly 1,200 Lebanese — mostly civilians — dead, pushing large swathes of the country into ruins.

“To be sure, Hezbollah can obstruct the negotiations any time and they hold the process hostage,” Shehadi told Arab News. “The theatrics of sending drones to take photos of the Israeli gas installations were in keeping with its approach.”

The Lebanese government officials whose histrionics too made headlines recently were Walid Fayyad, the energy minister, and Hector Hajjar, the social affairs minister, with their act of throwing rocks toward Israeli territory.

The duo, both linked to Aoun’s FPM, were part of a group of eight Lebanese ministers who were on a border-area tour. In the video, which went viral after it was broadcast by Al-Jadeed TV, Fayyad and Hajjar could be heard teasing each other about their rock-throwing abilities.

Lebanon's Minister for Social Affairs Hector Hajjar (R) throws a stone while Energy Minister Walid Fayyad (L) watches during a visit to the southern border with Israel on August 30, 2022. (AFP)

Fayyad, who in the clip tells Hajjar to “step aside, so I won’t hit your head,” is a frequent interlocutor for the Lebanese government during the discussions with Hochstein on the boundary dispute with Israel. Michael Young, a senior editor with Carnegie Middle East in Beirut, surmises that the two ministers’ actions may have something to do with the upcoming presidential election to find a successor to Aoun.

“I am not sure if it was planned that way, but the effect was showing that they stood with the ‘resistance against Israel,’” he told Arab News.

Shehadi concurred, saying that “everyone is playing along, including the cabinet ministers”, adding: “The new independent MPs who visited the border danced the (Levantine folk dance) dabke there. It’s all part of a subtle internal Lebanese political dialogue.”

To Shehadi, the scenes on the border were reminiscent of the period immediately after the Israeli withdrawal from Southern Lebanon in May 2000, when Lebanese politicians joined in the theatrics of the “liberation by the resistance.”

Lebanese high school students dance at Fatima Gate in Lebanon's southern border town of Kfar Kila on June 2, 2000 to celebrate the Israeli army pullout. (AFP)

“The circumstances of the withdrawal were well known. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak had promised in July 1999 to withdraw to the international border and it was a fulfillment of that pledge,” Shehadi told Arab News. “The withdrawal was coordinated between Israel and Hezbollah with the help of two Swedish mediators.”

This time around, Lebanese analysts are watching closely for any political fallout of the obvious gap between the rhetoric and actions of Nasrallah in the context of the Lebanon-Israel negotiations.

Since the Islamic revolution of 1979, the regime in Tehran and its Shiite proxies have relied on a formula of seeking to co-opt the Palestinian resistance to increase their moral standing in the Arab world. They have intervened in neighboring countries, and justified this as necessary to liberate Palestine with such cross-sectarian slogans as “The path to Jerusalem passes through Karbala.”

As part of the same playbook, Hezbollah has constantly tried to portray itself as a pan-Islamic force fighting, first and foremost, for the Palestinian cause, determined to liberate Jerusalem from “Zionist occupation” while accusing Arabs of abandoning the holy city.

Hezbollah (yellow) and Amal (green) supporters demonstrate near the Israeli-Lebanese border, with graffiti depicting Iran's slain "Quds Force" commander Qasem Soleimani in Lebanon's southern town of Kfar Kila on May 25, 2022. (AFP)

In a speech in Beirut’s suburbs in 1998, Nasrallah reportedly called for the assassination of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat for signing peace treaties with Israel by invoking the example of the killer of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981. “Is there no Palestinian who can do what Khaled Islambouli did and say that Arafat’s presence on the face of this Earth is shameful to Palestinians and Muslims?” Nasrallah had thundered.

As recently as in August 2020, he was fulminating against the signing of the normalization agreement between Israel and the UAE. “This is a betrayal of Islam and Arabism, it is a betrayal of Jerusalem, of the Palestinian people,” he said during a speech commemorating the anniversary of the end of Hezbollah’s 2006 conflict with Israel.

Fast forward to September 2022 and, as Michael Young, the Carnegie Middle East editor, puts it, “Hezbollah today is engaged in indirection negotiations with Israel.”

Supporters of Lebanon's Iran-backed Shiite group Hezbollah attend a rally to listen to the speech off Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in the southern city of Nabatiyeh on May 9, 2022. (AFP)

“To an extent, Hassan Nasrallah’s upping the ante is to show that they are not negotiating indirectly with Israel, signing what may be a deal on offshore gas sharing. But no one doubts that they are negotiating indirectly with Israel,” he told Arab News.

“At the same time, Hezbollah needs to show its domestic supporters that it’s still anti-Israel, hence the escalation of threats and criticism of Israel if Lebanon’s gas rights are not respected.”

But if a deal materializes, sooner or later, will Hezbollah tie its own hands by neutralizing the “resistance” and saying that Israel has respected all its commitments to Lebanon? “Hezbollah’s view is much wider than that,” Young said. “As long as there’s an enemy, the resistance must continue. This is not the official view of the Lebanese government but it is implied in all Hezbollah statements.”

Israeli navy vessels patrol along the coast of Rosh Hanikra, an area at the border between Israel and Lebanon (Ras al-Naqura), on June 6, 2022. AFP)

Young believes that at this stage, Hezbollah does not want to negotiate the entire sea and land border. “The focus now is on the maritime border. I don’t believe there’s willingness to negotiate anything dealing with the contested border, the Shebaa Farms,” he told Arab News, referring to a small strip of land occupied by Israel since 1967.

“(But) the UN says the occupation ended with the Israelis’ withdrawal in 2000. The Lebanese position on Shebaa Farms is not the same as that of the Israelis or the UN.”

As for the negotiations over the maritime dispute, Young says if media reports are any guide, the Biden administration has been putting pressure on both Lebanon and Israel and there are signs of progress.

“I don’t think we can rule out an agreement,” he told Arab News. “I think all sides have an interest in one and we are moving to a potential agreement.”

According to the White House official who spoke to Al-Arabiya, Hochstein is in communication daily with both Israeli and Lebanese government officials.