DUBAI: Even before the economic collapse in Lebanon, Syrian and Palestinian refugees living there were struggling to get by. Many chose to uproot themselves once again and set out in search of a better life overseas, often turning to people smugglers for help.

Now, the situation looks so hopeless that a growing number of Lebanese citizens who lack the means to pay for safe and legal passage abroad are also risking their lives to make the same dangerous, illegal sea crossings to Europe.

In early June, the Lebanese military apprehended 64 people in the north of the country who were attempting to board a smuggling vessel bound for Cyprus. Among them were several Lebanese citizens, driven to desperation by severe economic hardship.

“I cannot feed my family. I feel like less of a man every day,” Abu Abdullah, a 57-year-old delivery worker from Tripoli, the poorest city in the country, told Arab News. “I would rather risk my life at sea than hear the cries of my children when they grow hungry.”

Inflation, unemployment, shortages of food, fuel and medicine, a crumbling healthcare system, and dysfunctional governance have created a perfect storm of poverty and hopelessness.

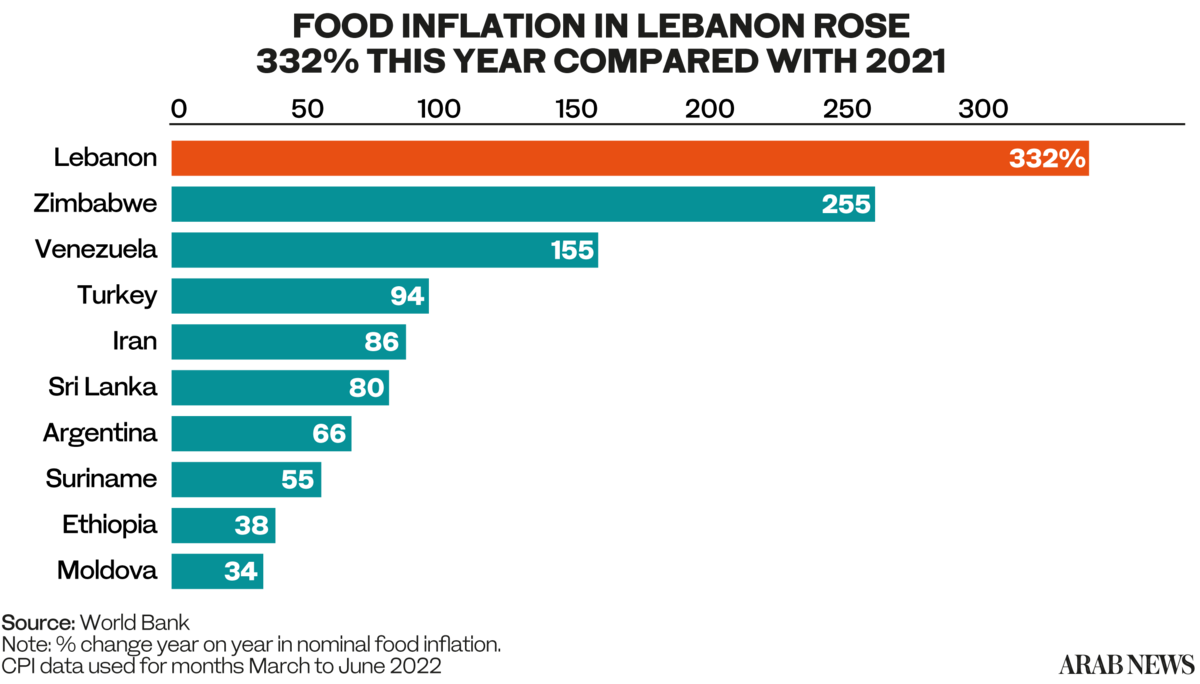

Shortage of grain as a result of the war in Ukraine has compounded Lebanon’s economic woes, with the prices of staples skyrocketing. Queues for bread are a common sight in many towns while public-sector workers have often gone on strike demanding better pay.

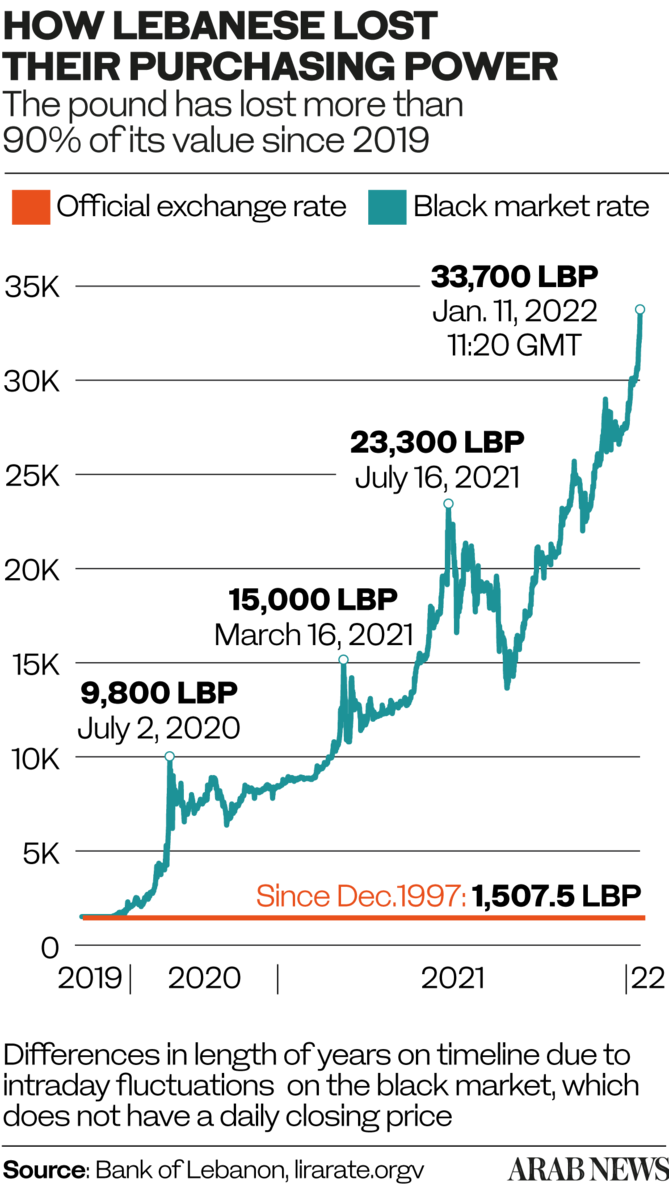

The nation’s currency has lost about 95 percent of its value since 2019. As of July, the minimum monthly wage was worth the equivalent of $23 based on the black market exchange rate of 29,500 Lebanese pounds to the dollar. Before the financial collapse, it was worth $444.

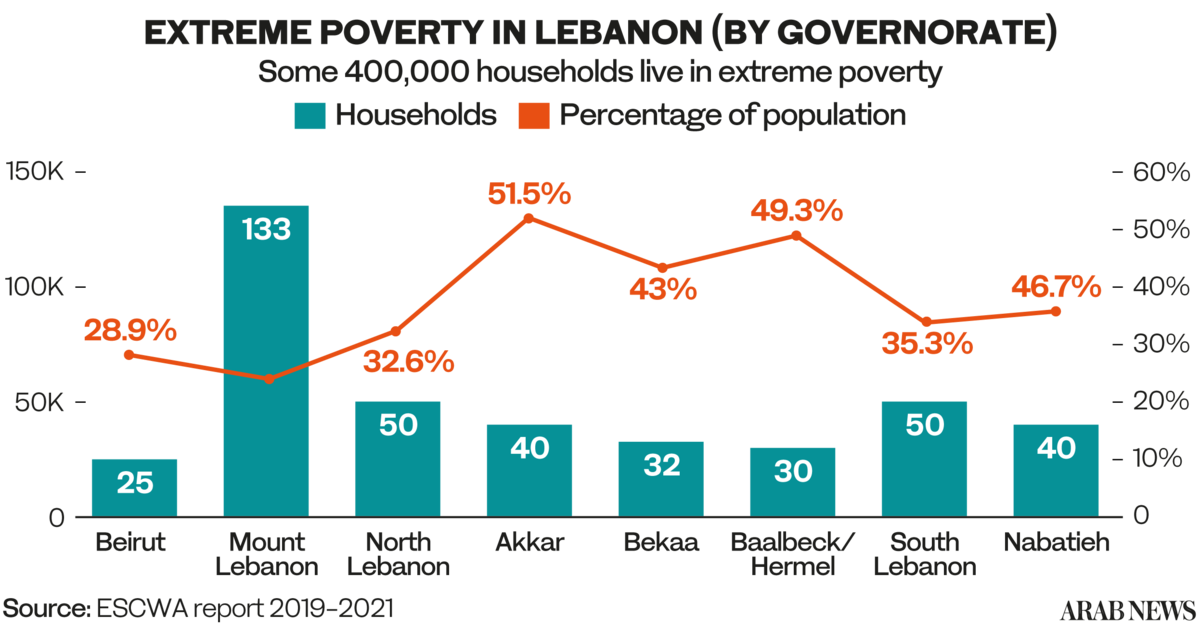

About half of the population now lives below the poverty line.

“My salary barely lasts a few weeks and the tips I get amount to nothing,” said Abu Abdullah. “One of my sons roams around the neighborhood dumpster diving, looking for tins and plastic to sell. It breaks my heart having to see him do this. But in order to eat we don’t have another choice.”

Since 2019, Lebanon has been in the throes of its worst-ever financial crisis. The effects have been compounded by the economic strain of the COVID-19 pandemic and the nation’s political paralysis.

For many Lebanese, the final straw was the devastating explosion at Beirut’s port on Aug. 4, 2020. At least 218 people were killed and 7,000 injured by the blast, which caused at least $15 billion in property damage and left an estimated 300,000 people homeless.

These concurrent crises have sent thousands of young Lebanese abroad in search of greater financial security and more opportunities, including many of the country’s top medical professionals and educators.

For those who remain and feel they no longer have anything left to lose, the thought of paying people smugglers to illegally ferry them across the Mediterranean to an EU country has become increasingly appealing, despite the obvious dangers.

In April, a boat carrying 84 people capsized off Lebanon’s coast near Tripoli after it was intercepted by the navy. Only 45 of the people on board were rescued. Six are known to have drowned, including a baby. The rest are officially classified as missing.

“A relative of mine lost her husband and toddler at sea around two years ago,” said Abu Abdullah. “The tragedy still haunts the family. And yet, here I am mulling and entertaining the thought that I should get on the next boat.”

The situation is perhaps even tougher for the millions of Syrian and Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon. Long treated as an underclass and denied access to several forms of employment and welfare, many of them now face a similar dilemma of whether to stay put or attempt a risky journey.

Medics wait on the pier as soldiers search for survivors off the coast of the nothern Lebanese city of Tripoli after a migrant boat capsized. At least six people died and almost 50 others were rescued. (AFP)

“I escaped the war in Syria and lived in Lebanon for three years,” Islam Mejel, a 23-year-old Syrian Palestinian, told Arab News from his new home in Greece.

“I tried time and time again and applied for visas to travel legally by land but who would give a Syrian Palestinian man a visa? I fled from Lebanon — I had to. I am the eldest and have to take care of the family I left back in Lebanon.”

Mejel described the terrifying ordeal he experienced while crossing the sea to Greece.

INNUMBERS

* 22% of Lebanese households now considered food insecure.

* 1.3m Syrian refugees in Lebanon categorized as food insecure.

(Source: World Food Program)

“We were a group of 50,” he said. “They split us between two small boats. The boats couldn’t handle the passengers. The second boat sank. Some survived and the rest were lost at sea.

“When we finally made it to a Greek island, the captain scuttled the boat and radioed for organizations to come and help us. Then he left. I knew the chances of me dying were high but I had to try.”

The extreme risks that refugees are willing to take to find security and economic opportunity abroad, often after having been displaced several times, speak volumes about the severity of Lebanon’s socio-economic collapse.

“For Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, there were already multiple layers of vulnerabilities they were exposed to prior to the crisis, such as the prohibition on owning houses or property and prohibitions on working in liberal professions, alongside limited social and political rights,” a researcher of Palestinian refugee issues in Lebanon, who asked not to be named, told Arab News.

“What’s happening now is an accumulation of crises built over time — COVID-19, the economic collapse — that have built upon pre-existing vulnerabilities the Palestinian refugee community previously faced in Lebanon.”

The researcher said the rate of illegal immigration, according to some sources, has increased in recent months, particularly among the youth.

One well-known trafficker is said to charge more than $5,000 to get a person out of Lebanon by plane, transiting through three airports before arriving in Europe where the migrants tear up their identity papers and apply for refugee status. For those without the financial means for this air route, the option of traveling by sea is less expensive but much more risky.

However, some sources the researcher spoke to said the rate of illegal emigration is currently in decline owing to the astronomical sums charged by smugglers even for the cheaper options. Such is the desperate state of personal finances in Lebanon that even a potentially deadly sea crossing is now beyond the means of many.

Lebanese families are risking their lives to escape. (AFP)

This is why some are reportedly opting to apply for a program called Talent Beyond Boundaries, which offers work visas for Palestinian youths seeking employment in other countries.

Lebanon was regarded by its citizens and foreign investors as a land of promise after the end of the civil war when the buzz of reconstruction replaced the rhetoric of sectarian slogans.

But these days, its citizens, as well as the people from neighboring states who found refugee in Lebanon, are looking abroad for opportunity and economic security. As a result the country is being deprived of the skilled young workers it will need to recover from the current crisis.

The general consensus is that until Lebanon’s political paralysis can be overcome and long-delayed economic reforms are implemented, the human tide is unlikely to stop. “It was a humiliation, day in, day out in Lebanon,” said Mejel. “I couldn’t take it anymore.”