JEDDAH: Health officials in Europe and the Americas are raising the alarm over the spread of monkeypox, with many declaring the outbreak a public-health emergency.

In Saudi Arabia, by contrast, where just three cases have been confirmed, the response has been more muted.

Saudi experts say there are several reasons for the Kingdom’s restrained approach, including the presence of well-established surveillance, detection and preventative measures resulting from its handling of previous infectious-disease outbreaks, and the extremely low transmission rate seen in the region.

“We know that especially in the Gulf region and in Saudi Arabia, there have been many efforts to document increasing cases and implement rigorous methods for detecting them, making sure that the right preventative and curative measures are in place to prevent the spread of monkeypox, as well as treating it right away from a medical standpoint,” Dr. Nawaf Albali, a Saudi physician, told Arab News.

“Countries have to implement the proper monitoring and surveillance standards on the borders and increase screening, increase diagnostic capabilities within and beyond borders.”

Once a relatively rare disease, monkeypox has been present in a handful of central and west African countries since the 1970s, with occasional outbreaks of no more than 100 cases over the past four decades.

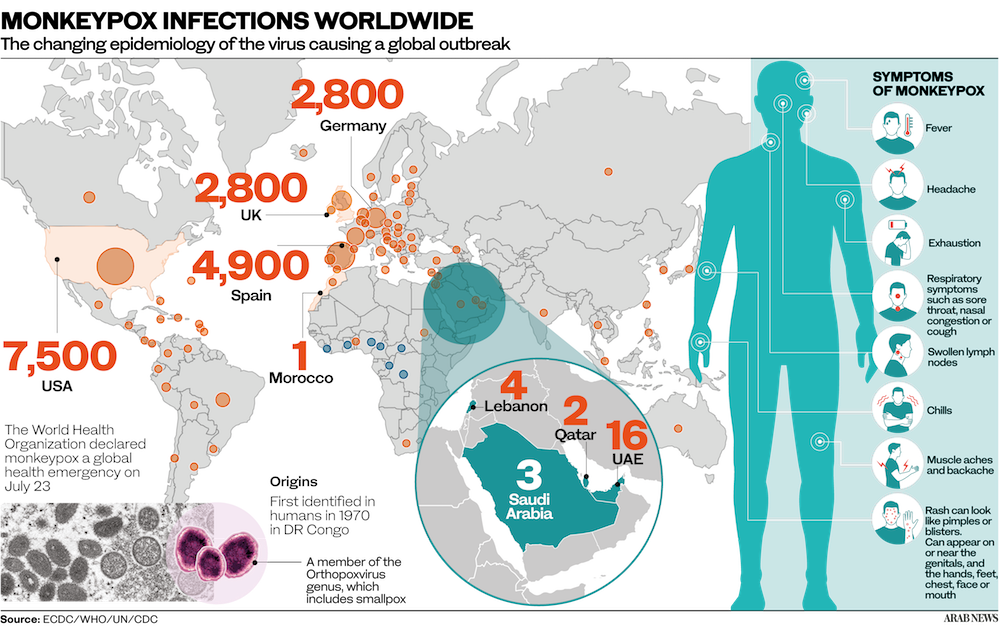

People with the illness tend to develop a rash that may be located on or near the genitals or anus, and on other areas such as the hands, feet, chest, face or mouth.

The rash will go through several stages, including scabs, before healing. It can initially look like pimples or blisters, and may be painful or itchy.

Other symptoms can include fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, exhaustion, muscle aches, backache, headaches, a sore throat, nasal congestion or a cough.

These symptoms usually start within three weeks of exposure to the monkeypox virus, and will typically last two to four weeks.

Authorities have detected dozens of cases across Europe, North America and beyond since May, breaking the 28,000-case mark worldwide.

Symptoms of the self-limiting disease typically last from two to four weeks. (Shutterstock)

The World Health Organization declared monkeypox a global health emergency on July 23. To date, there have been at least 75 suspected monkeypox deaths in Africa, mainly in Nigeria and Congo.

On July 29, Brazil and Spain both reported deaths linked to monkeypox, the first reported outside Africa. Spain reported a second death the next day, and India reported its first on Aug. 1.

Just three cases of monkeypox have been detected in Saudi Arabia, among passengers returning from Europe.

Regionally, the UAE has 16 confirmed cases and Qatar has two — indicative of a much slower spread compared to other parts of the world.

Monkeypox is transmitted when a person comes into contact with the eponymous virus from an animal, human or contaminated material.

It often spreads through skin-to-skin contact, and many, though not all, cases have been through physical relations between men.

“The way it spreads is either through skin-to-skin contact, or through contact with certain body fluids, for example sweat, or exposure to sensitive parts in the body like the genitals or private parts,” said Albali.

“This type of contact and this kind of intimate contact aren’t that common (in the Gulf). It doesn’t mean that they’re not there, but they’re not as common.”

Health officials in Europe and the Americas are raising the alarm over the spread of monkeypox. (AFP)

Dr. Abdulaziz Al-Angari, assistant professor of epidemiology at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences in Riyadh, said although the WHO has declared monkeypox a public-health emergency of international concern, it is not yet a pandemic.

“The rate of infection is slow and limited considering the transmission pathways of the virus,” he told Arab News.

To calculate an odds ratio (a statistic that quantifies the strength of the association between two events), a sufficient number of cases needs to be considered. To date, there have been too few cases in the Kingdom to draw conclusions.

“More detailed information about the cases such as survey investigation (demographic data, history, practices, traveling information etc.) is needed,” said Al-Angari.

Saudi Arabia and several other countries have taken necessary steps to gather such real-time data and prevent the spread — lessons that were learned from previous viral outbreaks.

In 2012, the first case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome caused by the MERS coronavirus was identified in Saudi Arabia.

Studies have shown that humans are infected through direct or indirect contact with infected dromedary camels, but the exact transmission route remains unclear.

The experience prompted the Kingdom to develop detection and containment strategies and infrastructure, which swung into action in 2020 when COVID-19 emerged.

Registered pharmacist Sapna Patel demonstrates the preparation of a dose of the monkeypox vaccine at a pop-up vaccination clinic. (AFP)

The Ministry of Health launched a command-and-control center, and accelerated the establishment of the Saudi Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Our experience with MERS-CoV was painful and peculiar in our region, and between 2013 and 2015, health authorities understood the magnitude of disease prevention, lockdowns, closing of markets and certain commercial activities related to camels,” said Albali.

“So we understand the effectiveness of early intervention when it comes to disease control. We’ve developed that kind of capability and the sense of urgency around the world health system.”

Reiterating the importance of early detection and documenting cases, Al-Angari said: “The global health systems developed critically after the recent pandemic in data collection, surveillance and tracking systems.

“With this, contact tracing is a must to prevent the upcoming introduction of the virus to new populations.

“Although it might not be necessary now, using systems such as the Tawakkalna app might be considered at some point.”

The Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority developed Tawakkalna to support the government’s efforts to confront COVID-19 by managing the process of granting permits for leaving home during the lockdown phase, which helped limit the spread of the virus.

In June, the app received the UN Public Service Award 2022 for institutional resilience and innovative responses to the pandemic.

The Kingdom understands the effectiveness of early intervention when it comes to disease control, according to Dr. Abdulaziz Al-Angari, assistant professor of epidemiology at KSAU-HS. (Supplied)

With travel demand skyrocketing after the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions, Al-Angari underscored the importance of monitoring points of entry.

“Since the (monkeypox) virus is transmitted from human to human, all necessary arrangements should be implemented,” he said.

“Activation of thermal cameras is necessary at all times, not only for this disease but for all future ones, and random health screening of people who are in contact with animals on a regular basis is important to prevent zoonotic diseases.”

Just like the early days of COVID-19, infrared cameras placed at airport arrival halls are an integral part of the syndromic surveillance process — a process of collecting, analyzing and interpreting health-related data to provide an early warning of health threats.

“Once a camera detects one of the symptoms of the illness (such as elevated body temperature), the case is isolated at the airport, and as part of Saudi Arabia’s preventive measures, other individuals that could’ve potentially been exposed to the case must also be tested,” said Albali.

“That’s how the cases were detected, and an investigation was launched after, with no other cases detected to date.”

Beyond surveillance, according to Albali, health authorities must provide sufficient information and guidelines for travelers heading to countries considered monkeypox hotspots.

“The main lesson learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is a heightened community awareness about the virus and how to protect themselves,” he said.

“The same rule of thumb now applies to this current outbreak, even though it’s barely made a mark on our shores in Saudi Arabia, and with the transparent communication strategy by health authorities, the level of awareness will continue to increase and further protect the community from future outbreaks.”

Monkeypox immunization programs have been launched in the US, the UK, Denmark, Spain, Germany, France and Canada among other countries. However, Saudi Arabia is unlikely to launch a vaccine rollout unless it becomes necessary for the purpose of protecting the most vulnerable, such as children, the elderly and the immunocompromised.

Although monkeypox in most cases has no complications, the Saudi Ministry of Health told Arab News that the vaccine is available as a precautionary measure and is given only to people who are at higher risk for infection because they have had contact with confirmed cases.

“Vaccines can be implemented,” said epidemiologist Al-Angari with the caveat that distribution on a mass community level is unlikely to happen in the Kingdom because monkeypox “isn’t a current threat, at least (not) in this region.”