DUBAI: “In the aftermath of British colonial rule, a few crucial weeks in 1947 initiated complex and still-unresolved processes of displacement, fragmentation, conflict, and nation-building that spanned decades, and which continue to deeply scar the societies and peoples of the subcontinent.”

This is how Dubai’s Jameel Arts Center introduces its latest exhibition, “Proposals for a Monument to Partition.”

It is 75 years since partition divided British India into two independent dominions — India and Pakistan (which was later divided again into Pakistan and Bangladesh) — leaving millions of people displaced along religious lines and creating what is believed to be the biggest refugee crisis ever (mass migration continued for many years afterwards). It also sparked outbreaks of widespread violence that left hundreds of thousands (a conservative estimate) dead on both sides of the newly created border.

Little wonder, then, that the show’s curator, the Sharjah-born writer and art historian Murtaza Vali, describes partition as a “foundational trauma” — one which still has a marked influence on events in the Global South.

For Vali, “Proposals for a Memorial to Partition” brings together a number of themes that have occupied his thoughts for many years — including trauma, displacement, nationalism, and the rise of authoritarianism.

The idea for the show had its seeds in work Vali did for the 10th Sharjah Biennial in 2011, when he was invited to contribute to a project called “A Manual For Treason.”

Sharjah-born writer and art historian Murtaza Vali is the show curator. (Supplied)

“I was very interested in the dialectical tension between treason and patriotism and how it’s basically the sovereign power of the nation state that decides who’s considered a traitor and who’s considered a patriot,” Vali tells Arab News. “In the South Asian context, nationalism looms large. Nationalism was the movement that helped us gain independence. So nationalism has this very strong anti-colonial bent that also brings with it a liberatory politics. But there were also very important thinkers who were suspicious of nationalism and its ills from the very beginning.

“Growing up as a South Asian in the UAE, I felt this draw to national identity — because I grew up with this feeling of never being entirely at home where I was — but also a suspicion of it,” he continues. “So, I came up with six essays that were looking at liminal figures who straddled this very fine line between treason and patriotism.” He also invited six artists to contribute work to the book. “I had to explore a format that made sense in that context and I came up with this idea of soliciting proposals for a memorial to partition,” he explains.

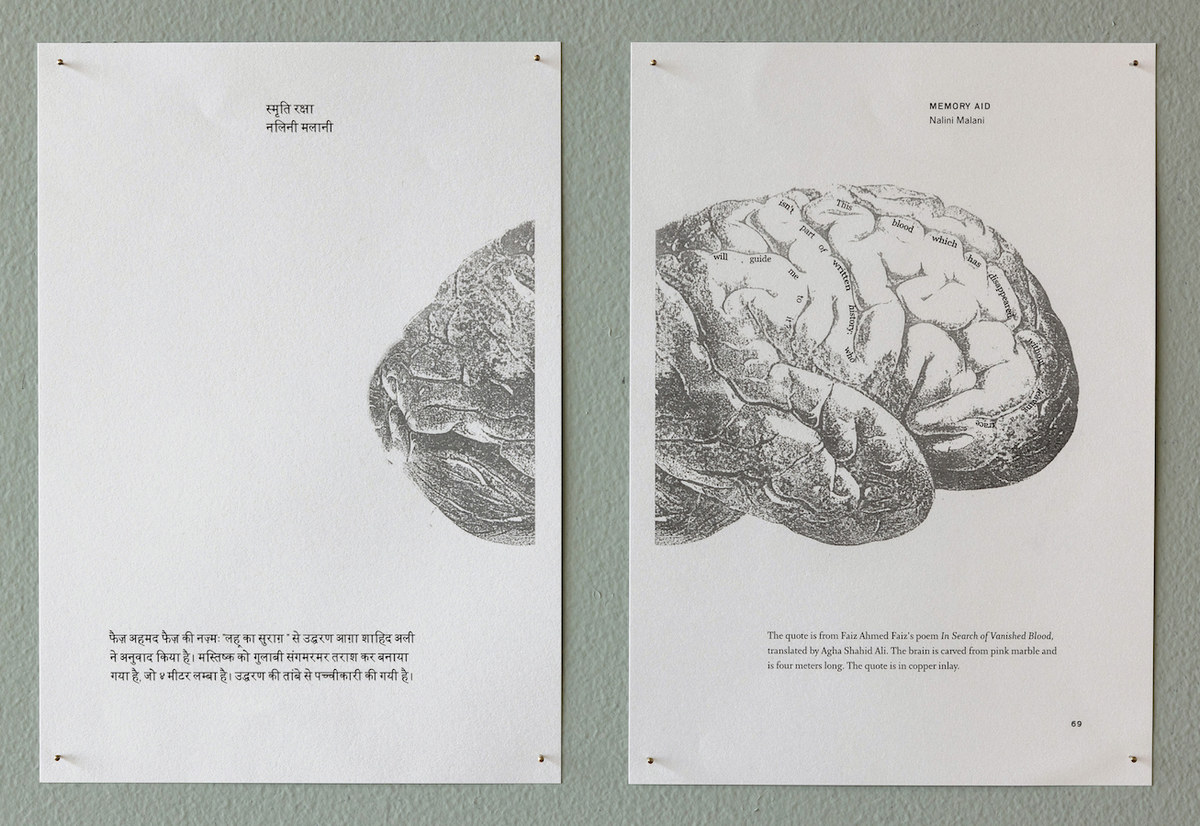

Nalini Malani, ‘Memory Aid.’ (Supplied)

Partition, Vali says, had been on his mind for a while. His interest in artists dealing with history meant he was aware of “one or two important works … that grappled with the legacy of partition,” but as he dug further, he found that there was also “this kind of absence around the subject, which was especially telling in visual arts and culture. Very few artists in the decades following partition tried to grapple with, or represent, the violence, displacement and trauma that was associated with it.”

“So, I got quite fascinated with this idea of absence,” he continues. “What about this event made it, in some sense, unrepresentable? It’s like with the Holocaust: It’s such a horrific incident that it becomes unrepresentable in contemporary terms."

“So that’s where this idea of coming up with proposals for a memorial to partition came in; to actually ask people to imagine a site, or an event, or a ritual, or an object, that would aid in addressing this absence of acknowledgement of a foundational trauma.”

Aside from the horrors of partition, Vali believes there are other reasons for that ‘absence.’ “It was an event that (went hand-in-hand) with independence,” he says. “So one of my theories is that because the violence — the riots, the murders, the abduction and rape of women — (was carried out) on both sides, it’s hard to identify (a single) culprit. So, everybody moves on and forgets about it. The other thing is that, with independence, there’s a strong push towards nation building and development and modernization, and the uplifting of the poor. And in that optimism, anything that troubles that spirit of nationhood gets swept under the carpet. I was interested in exploring some of that as well.”

Visitors view Bani Abidi's video installations ‘Mangoes’ and ‘Mother’s Lands’ and Nabla Yahya’s ‘Silsila’ cyanotypes. (Supplied)

From those six original proposals, the project has now expanded (and may continue to do so, Vali says he always envisioned it as “an accumulative project”) to include three newly commissioned works and proposals from a dozen other artists. The multitude of proposals (which include the cross-border collection of plant seeds, a syllabus, an audio installation, and more), he explains, is intentional — acknowledging that there can be no one memorial that would suit everyone. And the proposal format allows “a degree of poetic, or Utopian, or surreal thinking; it takes some of the pressure off because the project never has to be realized.”

The results are certainly thought-provoking, often simple — as basic as a t-shirt, say, or Amitava Kumar’s suggestion for giving ‘pairs’ of gifts, with each pair consisting of an item from each country — and often emotive. Faiza Hasan’s moving proposal, for example, combines charcoal drawings of her grandmother’s photographs and bric-a-brac with official documents, including one stating that a requested birth certificate cannot be issued because “the concerned register is not available”; Dubai-based artist Nabla Yahya created “Silsila,” a series of cyanotypes, the centerpiece of which is a photograph of the original document acceding Kashmir.

“There were a couple of people (from Kashmir) who came up to me,” Vali says, “and were, like, ‘It’s amazing that everything that has happened in the last 75 years, all the violence and the injustice — the document that set it in motion is so banal.’”

Amitava Kumar, ‘Small Proposals for a Memorial,’ series of four digital drawings. (Supplied)

There is also humor here, most obviously in an installation from Pak Khawateen Painting Club — a collective of Pakistani women artists — which resembles the kind of anonymous government office familiar to so many of us, where time seems to stretch out endlessly while you wait for someone to stamp something: A brown wooden desk, a pot plant, neatly arranged folders; a swivel chair…

“They came back to us with this idea of creating a folder of discourse between different departments in any kind of bureaucratic structure — each of them took on a role in a different department,” Vali explains. “All of the communication is entirely fake — basically an illustration of how post-colonial bureaucratic inertia makes it almost impossible to realize a project like a memorial to partition.”

The variety of approaches on display seems to confirm Vali’s theory that there can be no one memorial to this event. But perhaps the show itself could fulfill that role? It is certainly a powerful attempt. And relevant.

“I think partition is this trauma that repeats cyclically, so a lot of the ongoing problems across South Asia are all traumatic returns of partition,” Vali says. “I hope the show gives people an opportunity to reflect on that and have conversations around this subject.

“I also hope that — in whatever little way — the show brings that spirit of always tempering patriotism with a degree of self-reflection about what it means. It comes back to something that I hold dear, which is that it’s important to be suspicious of nationalism,” he continues. “It is a powerful, powerful rallying cry, and it’s a source of identity and belonging, but it can also very quickly turn dark.”