DUBAI: As Egyptian-Swedish filmmaker Tarik Saleh sat in the audience the 2022 Cannes premiere of his latest film, “Boy from Heaven,” he found himself unable to focus on his own accomplishment. Even as his hero, the legendary Greek filmmaker Costa-Gavras, turned from the seat in front of him to offer a nod of approval, even as more than 2,000 enraptured guests sat on the edges of their seats behind him, all Saleh could think was, “I wish someone else had made this.”

“If someone else would just make these films, I wouldn’t make them. I would just watch them,” Saleh told Arab News, speaking on the sidelines of the festival. “The problem is no one will make them unless I do. I guess some things I just have to do myself.”

One can see why others may have shied away from making a film like “Boy from Heaven,” which was awarded both Best Screenplay and the coveted François Chalais Prize at Cannes. After all, a thriller about the inner workings of the highly-influential Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo following the death of the Grand Imam and a corrupt political effort to replace him was always bound to draw controversy.

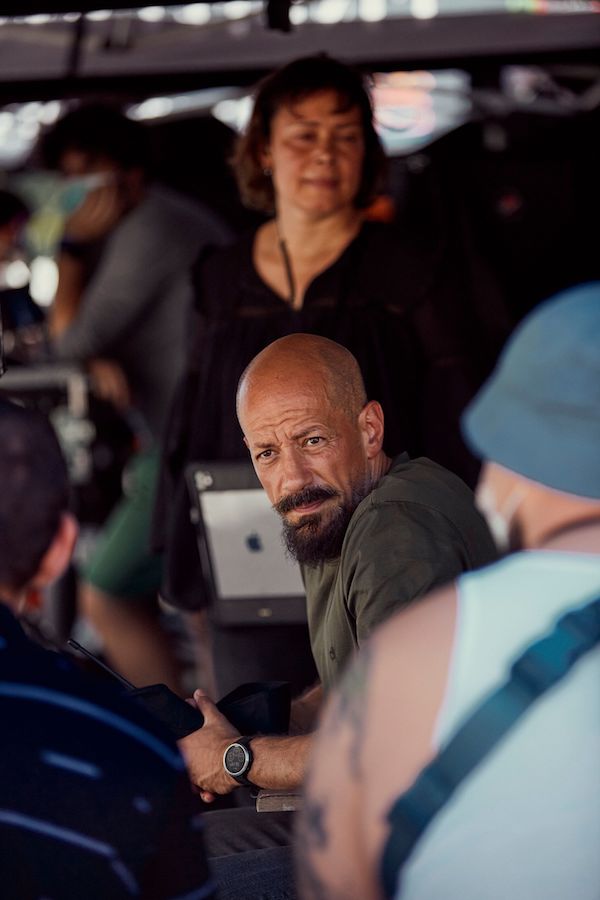

Saleh was born in Stockholm in 1972 to an Egyptian father and Swedish mother. (Supplied)

“The funny thing is, I don’t intend to provoke anyone — not that there’s anything wrong with a little provocation. I just want to tell a good story, and make a good film,” Saleh said.

The idea came to Saleh as he reread one of his favorite books, Umberto Eco’s “The Name of the Rose,” a murder-mystery set in an Italian monastery in the 14th century. It occurred to him what a similar scandal set in al-Azhar might look like, before he quickly dismissed the thought as impossible in the current political climate.

“I started thinking, ‘Are you allowed to tell that story? How will people react?’ I immediately started self-censoring — which made me realize that’s exactly why I have to tell it. I realized that if I told this story without holding back, I would walk out into territory that no one has ever been. That in itself is controversial,” says Saleh.

Saleh was born in Stockholm in 1972 to an Egyptian father and Swedish mother, and long before he ever even visited the country, he reflexively answered that he is Egyptian first. That’s because, growing up, none of his fellow Swedes would accept him as one of their own.

“Boy from Heaven” is an unflinching work that takes a critical view off the ways in which politics can affect things that are supposed to be immune to its workings. (Supplied)

“Every day here in Sweden, I was asked, ‘Where are you from?’ If I answered ‘Sweden,’ they would not accept that. After a while, I just gave up. I said, ‘I'm from Egypt,’” says Saleh.

As much as he resented being otherized, Egypt still held a dear place in his heart. And still does.

“My father, instead of telling me fairy tales and bedtime stories, would tell me stories from his childhood in Egypt. From there, it became almost like an obsession for me,” says Saleh.

Throughout his life, Saleh has also had to endure cultural hate towards Muslims and the Arab world, in which bigotry was often misrepresented as fact. He even found a book in his library in school called “Arab,” a pseudo-scientific study that described “the Arab” as stupid and uncivilized.

“I grew up constantly having to defend us, to defend Arab humanity,” Saleh said. “When I started writing my own scripts, starting with ‘The Nile Hilton Incident’ (2017), I gave myself permission to have the audacity to ignore the fact that the Western world has been brainwashed to think that people from the Arab world aren’t human. So I set out to tell a human story, with the good and the bad, and not try to convince anyone of anything.”

(From L) Actor Tawfeek Barhom, director Tarik Saleh and Lebanese-Swedish actor Fares Fares at a photocall for ‘Boy from Heaven’ at the Cannes Film Festival in May. (AFP)

Saleh was inspired by the films of Alfonso Cuarón and Alejandro Iñárritu of Mexico, and Bong Joon Ho and Park Chan Wook of South Korea, who each made films of overflowing humanity that transcended above cultural borders. He decided he, too, could make a film like Joon Ho’s remarkable “Memories of a Murder” (2003), a film that was critical of its society, offered no context or explanations, but was never considered an indictment of an entire people.

“To all the critics of ‘Boy from Heaven’ who will say I don’t provide enough context, I say no, sorry, I don't owe you an explanation,” Saleh said. “I'm not here to teach you about Islam. Bong Joon Ho doesn’t explain Korean society. He's not a teacher. He's a filmmaker. A lot of Western people think they have a right to know. I say, no, you have a right to learn. You’re going to have to take this journey yourself.”

That is part of the reason that Saleh chose to have the main character of “Boy from Heaven” himself be alienating to Western audiences, subverting the Hollywood expectation that the outsider character would stand in for a skeptical Western viewer’s perspective.

“I knew it would be unsettling to take this journey with a person who is a believer, who is trying to do the right thing. And I’m very glad that I made it unsettling,” the filmmaker said.

Tarik Saleh won Best Screenplay at Cannes for ‘Boy from Heaven.’ (AFP)

While “Boy from Heaven” is — first and foremost — an unflinching work that takes a critical view off the ways in which politics can affect things that are supposed to be immune to its workings, Saleh wanted, primarily, to be respectful to the faith and accurate in his depictions of the university — which his own grandfather attended — and the mosque and perhaps forge a deeper connection with them himself.

“I worked with an imam who was very knowledgeable about Al-Azhar. I wanted to make sure that the depiction was correct and — for selfish reasons — I wanted to have conversations with him about life, about moral issues, my own doubts and problems. It was very fruitful,” said Saleh. “We had many interesting conversations about the dilemmas in the film. I realized I’m sort of telling myself the story, in many ways.”

For Saleh, the film’s story is about himself as much as anyone else. Good storytelling, after all, brings the viewer into the minds of its characters, preferably in a way that makes them understand a deeper truth, both about themselves and the world around them.

“That’s the transcendent thing about film — when you’re watching it, you’re making the decisions the character is making,” Saleh said. “What’s even more spectacular is the more corrupt decisions they’re taking, the more we, as human beings, can relate.

“Our leaders try to tell us that the enemy is on the other side of the ocean, or the other side of a border. But the truth is our enemy is in the mirror,” he continued. “Human beings, if we’re honest with ourselves, know that we are up against ourselves. That’s the basics of drama, and the basics of life.”