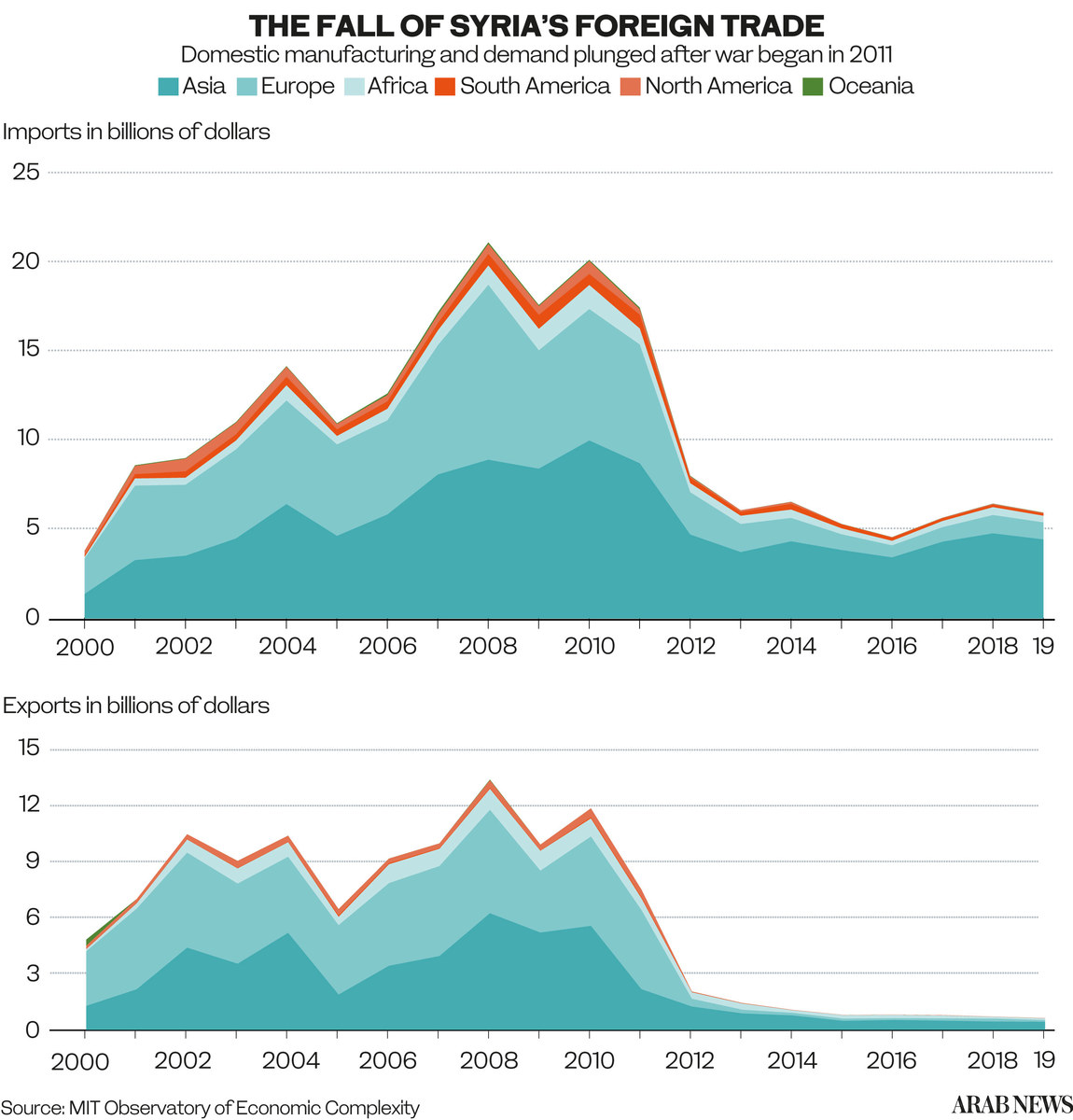

DUBAI: After more than a decade of civil war, regime-held Syria is in a state of economic ruin. Conflict, endemic corruption, drought and the mass migration of skilled workers have exacted a devastating toll, leaving the country ripe for exploitation.

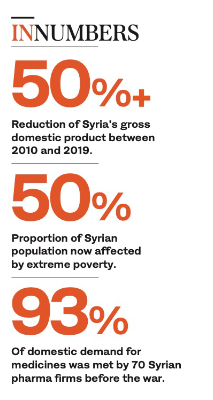

According to the World Bank, Syria’s gross domestic product shrank by at least 50 percent between 2010 and 2019, leaving more than 90 percent of the population below the poverty line and more than 50 percent facing extreme poverty. In this vulnerable state, Syria’s domestic markets have been flooded with cheap imports.

Iran, capitalizing on its military and political backing for the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad, has expanded its exports to Syria, exploiting and exacerbating the disintegration of the country’s manufacturing base by monopolizing entire markets.

The collapse of domestic industry since the war began in 2011 has provided businessmen close to the Assad regime with lucrative opportunities to import cheaply made goods from Iran, to the detriment of Syrian producers.

While few of the grandiose reconstruction agreements between Tehran and Damascus have broken ground as yet, Iran has succeeded in breaking into Syria’s pharmaceutical and food industries, muscling out the local competition.

Prior to the uprising that sparked the civil war, Syria had a thriving pharmaceuticals industry; about 70 factories nationwide met 93 percent of domestic demand and exported to about 60 countries.

However, a decade of war has left these factories and the power grid needed to sustain such industries in ruins. Violence and persecution have sent legions of skilled workers into exile, while sanctions have blocked access to raw materials and machine parts.

Light bulbs made in Iran have flooded the Syrian market. (Supplied)

As a result, by 2020 Syria’s overall pharmaceutical production capacity had fallen by about 75 percent.

“The active ingredients for medicines are very difficult to import and are very expensive,” Hamed, a student of pharmaceuticals nearing graduation at a leading Syrian university, told Arab News.

“Many factories stopped production lines due to shortages of the active ingredients and energy.”

Drugs close to their expiration date often find their way into Syria, where they are taken nonetheless by desperate patients. (AFP file)

The crisis facing Syria’s pharmaceuticals industry, along with similar challenges in the domestic agricultural sector, has been aggravated by a sharp devaluation of the currency that began in late 2019.

Tied to the banking crisis in neighboring Lebanon, the devaluation caused the import of crucial components — including, seeds, pesticides, fertilizer, diesel and the raw materials needed for the manufacture of medicines — to become exceedingly expensive.

Syrian companies and industrialists had long deposited their capital in Lebanese banks to avoid Western sanctions. When the Lebanese currency plunged in value, therefore, so too did Syrian deposits.

Meanwhile, the devastating decline of Syria’s power grid amid years of fighting and neglect has caused production to become even more expensive, as factories and cold-storage facilities have been forced to rely on costly private generators.

Power cuts in Syria has forced factories and cold-storage facilities to rely on costly private generators. (AFP file photo)

All of this is on top of endemic corruption, which has long necessitated the payment of bribes to local officials, along with the loss of essential staff to military conscription and displacement.

As the prices of Syrian-made products soared, foreign and domestic demand evaporated and the market for cheap foreign imports exploded.

The regime’s protectionist policies are equally disruptive. According to Hamed, “limitations imposed by the Ministry of Health” on the prices and export of Syrian-made medicines have rendered local manufacturing unprofitable and further fueled the growth of the black market.

The plunging value of the Syrian pound has made it profitable for Iranian importers to grab all the Syrian exports they could find. (AFP file photo)

The destruction of Syria’s productive capacity, combined with the depreciation of Iran’s currency under years of Western sanctions, has been a boon for Iranian exporters, who have been able to flood the Syrian market with cheap products.

Iran has been especially successful in exporting pharmaceutical goods to Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. It has organized trade fairs and signed distribution deals slanted in its favor, even though many consumers view Iranian-made medicines as substandard.

About 75 percent of the medicines sold on the Iraqi market are brought into the country through illegal border crossings with Iran. These drugs are often close to their expiration date or lack the required active ingredients to help patients.

Drugs close to their expiration date often find their way into Syria, where they are taken nonetheless by desperate patients. (AFP file)

According to Khedr, a Syrian pharmacist living in the west of the country, the quality of the Iranian medicines is “not great” and they are mostly found in state hospitals rather than private pharmacies, where the customers tend to favor better-quality alternatives.

Abdullah, a doctor at a hospital in Damascus, is similarly skeptical about the efficacy of the drugs from Iran.

“Iranian medications are found in all Syrian hospitals, and I use them in my practice as well, but they are not of good quality,” he told Arab News.

For many people living in Syria’s poverty-stricken communities, however, any medicine is better than no medicine. And with shortages rife, in part because of a black market trade in locally made goods, few have any choice other than to buy the Iranian brands.

For many people poverty-stricken communities in Syriae, any medicine is better than no medicine. (AFP file photo)

“Compared to locally made medicines, people try to avoid the Iranian ones,” said Hamid. “But, in recent months, some Syrian-made medicines have entirely disappeared from the market as they are being smuggled into Lebanon. So people are relying on Iranian medicine to a greater extent.”

Iranian-made opioids are also finding their way onto the black market. Such pain medications can be highly addictive, or deadly if taken in high doses.

According to Abdullah, such medications “require special types of prescriptions or can only be found in institutions belonging to the Ministry of Health, because they contain morphine and other opiates for painkillers.”

He added: “If one is caught with these types of medications (without a proper prescription), one can be arrested for drug dealing. But they’re flooding the market and it’s all Iranian-made.”

In May, the Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce hosted a forum in Tehran, during which representatives from the private sectors in the two countries exchanged ideas on how to expand trade ties.

In May, the Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce hosted a forum in Tehran, during which representatives from the private sectors in the two countries exchanged ideas on how to expand trade ties.

“Our plan is to increase the level of mutual trade to $1 billion in the first phase, and realizing this goal requires the strong presence of the Iranian private sector in Syrian markets,” Gholam-Hossein Shafeie, the head of the chamber, told delegates, according to the Tehran Times.

In part, the Syrian regime has been driven into the arms of Tehran, to get help rebuilding infrastructure and restarting the economy, by virtue of their shared pariah status. Both governments have been squeezed by Western sanctions and global isolation.

“We are ready to cooperate with the Iranian private sector to find solutions for removing barriers and neutralizing the impacts of the US sanctions,” Shafiq Dayoub, the Syrian ambassador to Iran, told the joint chamber.

Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis, right, and Iranian Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri shake hands after the signing of an agreement in the Damascus on Jan. 28, 2019. (AFP file photo)

However, a daunting problem this developing partnership faces is the trade imbalance between the two economies, which means Syria is the junior partner and allows Iran to set the terms.

“There is not enough foreign currency in Syria to pay for Iranian exports and also Syria does not have much to export to Iran in return,” Abbas Akbari, secretary of the Iran-Syria Economic Relations Development Headquarters, told the forum.

Iranian candy products have replaced locally made sweets in many parts of Syria. (Supplied)

It is Syrian farmers and manufacturers who pay the price for this trade imbalance. Just like the situation in the pharmaceutical industry, a flood of cheap Iranian imports, combined with the Syrian regime’s strict controls on exports, has devastated the livelihoods of local food producers.

Where once Syria was a regional breadbasket, replete with fertile land and food-production facilities of its own, supplemented by imports from neighboring Turkey, it is now almost entirely reliant on imports of fresh and non-perishable goods from Iran.

A street vendor waits for customers in the main market of the rebel-held city of al-Bab in Syria's northern Aleppo province on the border with Turkey. (AFP file photo)

Once again, the quality of these products is widely considered to be lesser than the alternatives, but the lower prices mean they are nonetheless an attractive option for impoverished Syrian consumers.

“Today I cooked macaroni made in a factory named after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini,” Bassam, a farmer living in Hama, told Arab News.

Abu Omar, a farmer from western Daraa, told Arab News that farmers in southern Syria are banned from exporting their produce until the needs of the local market are satisfied. Yet at the same time, Iranian goods are allowed to flood the Syrian market during the harvest season, harming the ability of local farmers to turn a profit.

In this file photo, Syrians work on a small field in a camp for internally displaced. (Photo courtesy of FAO)

“The farmer comes out losing money at the end of the harvest, having bought pesticides and diesel in dollars, paid the agricultural engineer (providing the seeds) in dollars, and his workers,” said Omar.

Farmers in southern Syria have appealed to the government for additional help but few dare to suggest that a halt to Iranian imports is needed to reset the balance.

“This is a state policy. A person can’t change it,” said Omar. “And if you offer your opinion, you can walk yourself right into prison.”