DUBAI: Across Iraq, water sources that have been taken for granted and relied upon throughout centuries of hardship, chaos and drought are under threat. So too, as a result, are the livelihoods of many people in the country who find themselves facing unprecedented challenges in accessing one of life’s essential resources.

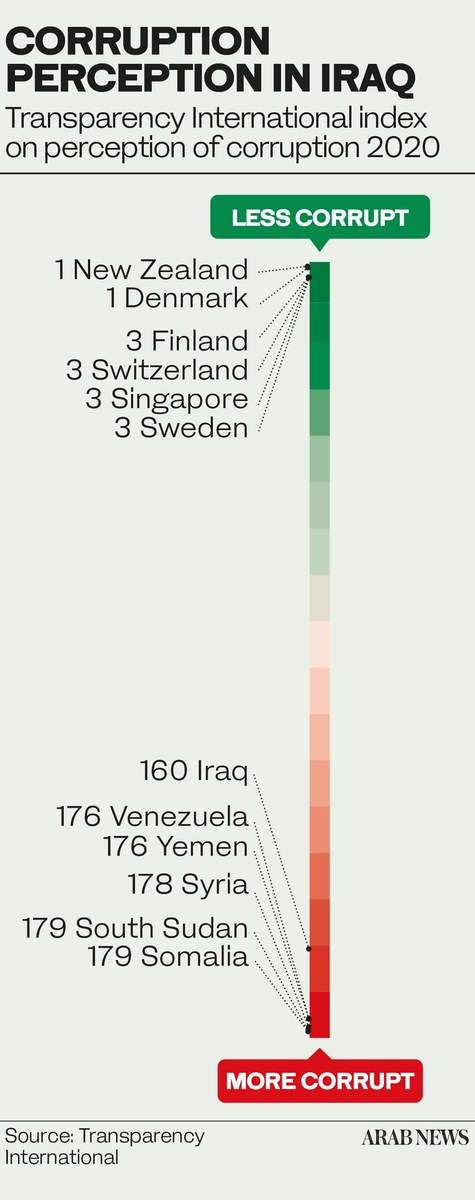

A combination of conflicts, corruption, mismanagement and regional political disputes has left the people of Iraq facing chronic water shortages that are having severe effects on the country’s agriculture, economy and the health of its citizens, so much so that the viability of many communities is now in question.

Over the past five years Baghdad residents have grown used to the sight of islands of land protruding along the Tigris River where once only its mighty waters were visible. It is a phenomenon associated with rivers in which water levels have dropped to record low levels as a result of decreasing volumes.

As a result, a number of barren islands now dot the surface of one of the world’s most storied waterways as it meanders meekly through the Iraqi capital, a shadow of the swift, green torrent that helped sustain the ancient land through the ages.

Salam, who gave only his first name, is a taxi driver who has lived in Baghdad all of his life. In years gone by he watched the Tigris roar through the city but he said its flow has diminished over the years and now he can see the narrow riverbed.

“I’m doing better than most in the rest of Iraq,” he told Arab News. “My water charges are still relatively affordable but I do have to buy a lot of drinking water for cooking as I cannot use tap water, which is way too contaminated.”

He has friends and relatives in Diyala, in central-eastern Iraq, and for them he said it is a different story.

“My farmer friends are struggling, so I often lend them money to get by. May God help them,” he explained.

In southern Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers combine to spill into the fabled Mesopotamian Marshes, buffaloes drink from stagnant pools of polluted water and farmers paddle traditional canoes through what used to be pristine potable water but now more resembles industrial sludge.

The livelihoods of millions of people are in peril as diminishing river volumes compound the effects of low rainfall and heat waves in Iraq. (AFP)

The supply of freshwater to the once mighty rivers has been restricted at their sources by dams built in Turkey, which have blocked much of the flow of the Euphrates and Tigris into Syria and Iraq.

The two rivers supply 98 percent of Iraq’s surface water. Other water sources have been stemmed in Iran, which means that the once-reliable volumes of water that helped staved off famine and sickness, even during years of dire drought, are now far from guaranteed.

In 2018, the UN classified Iraq as fifth in the world in terms of nations’ vulnerability to climate change. The effects have been clear over the past 15 years, with lower rainfalls and longer and hotter heat waves becoming more frequent.

Studies by the Iraqi government reveal that the country is now about 40 percent desert, and the salinity of much of the land is too high for agriculture.

In southern Iraq in recent years, water barely covers 30 percent of what were once marshlands but are now being replaced by dry, cracked earth, a sight locals were unaccustomed to.

The effects of the changing climate are tangible: The 2020-21 winter season was one of the driest on record in Iraq, marked by a reduction in water flow of 29 percent in the Tigris and 73 percent in the Euphrates. Rainfall has been increasingly sporadic over the past 20 years.

FASTFACTS

* Iraq’s population of 40 million is expected to double by 2050.

* The Tigris and Euphrates provide 98 percent of Iraq’s surface water.

* Precipitation is predicted to drop by 25 percent by 2050.

* More than half of cultivable land faces the threat of salinization.

For now, however, the regional politics of water is a more pressing problem. Finding ways to compel Ankara and Tehran to allow the Iraqi rivers to flow more freely is a challenge that preoccupies Iraqi officials.

Toward the end of 2021, Mahdi Rashid Al-Hamdani, Iraq’s minister of water resources, announced he planned to file a complaint against Iran for cutting the water supply at the border and causing a catastrophe in Diyala province. Iraqi authorities said their country has only been receiving one-tenth of an agreed quota. Meanwhile, the amount of water flowing from Turkey has diminished by almost two-thirds in recent years.

A report published by the Norwegian Refugee Council last year, titled Iraq’s Drought Crisis, found that many farmers have fallen into debt in an attempt to keep their livestock alive. It also revealed that one in two families in drought-affected areas need food aid. At least seven million Iraqis are affected by ongoing drought.

A tractor ploughing a parcel of agricultural land on the outskirts of the the town of Tel Keppe (Tel Kaif) north of the city of Mosul in the northern Iraqi province of Nineveh. (AFP/File Photo)

Farmers urgently require drought-tolerant seeds and additional feed for their cattle, goats and sheep to prevent further losses of livestock, according to Caroline Zullo, Iraq’s advocacy adviser at the Norwegian Refugee Council.

In the longer term, irrigation infrastructure for farmers must be established or rehabilitated, alongside improved water resource-management plans on local and national levels, Zullo told Arab News.

The effects of the drought across governorates have been significant, including crop and livestock losses, greater barriers to access to food, declining incomes, and drought-induced displacement of vulnerable families.

The effect of water scarcity on children, even in built-up, urban areas, has long been a cause for alarm. A 2021 UNICEF report titled Running Dry stated that nearly three out of five children in Iraq have no access to safely managed water. Many households have been forced to dig wells to obtain water that is not potable and, in some cases, unsafe even for necessities such as washing and laundry.

Water quality in the southern city of Basra is among the worst in the country, according to many studies. A report published by Human Rights Watch in 2018, titled Basra is Thirsty, stated that at least 118,000 people had been hospitalized in recent months suffering from symptoms related to issues of sanitation and water quality. At the time, the Basra health directorate urged people to boil water before drinking it.

The effects of water shortages on demographics in Iraq is evidenced by the thousands fleeing urban areas to the outskirts of larger cities, which in turn are struggling to cater for the needs of their new arrivals.

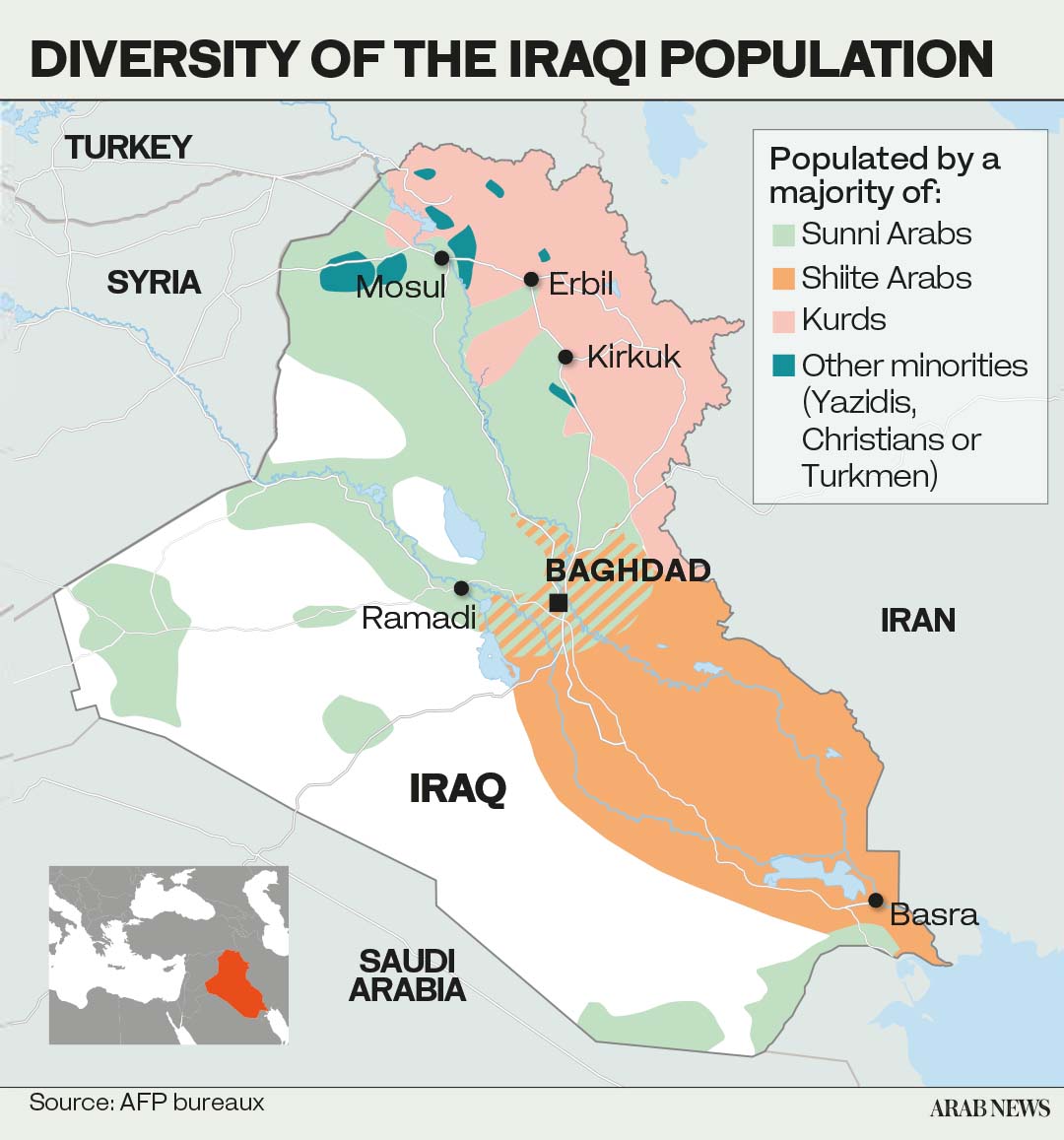

In the Kurdish north of the country, heavy snowfalls in the mountains in January have offered a reprieve so far this year. When winter turns to spring, the thaw will help to replenish reservoirs and prevent water scarcity before the onset of another fierce summer, where temperatures across Anbar province and deep into the country traditionally settle into the high 40s Celsius between May and mid-September.

Iraq’s central government remains weak and is therefore no match for powerful neighbors at the negotiating table. Five months after a national election, the country is still nowhere close to choosing a new president and prime minister or forming a government. If and when the political impasse ends, a weak and fractious government will still require international support to deal with a daunting challenge such as water security.

Rahman Khani, the head of the Kurdish Regional Government’s water resources and dams department at the agriculture ministry, said outdated methods are hindering the country’s water-management systems.

“We also suffer from pollution and traditional irrigation methods,” he told Arab News. “The solution is to reform internal water management, construct dams, and use modern irrigation technology, in addition to putting pressure on neighboring countries to release fair amounts of shared water.”

Looking to the future, experts say more must be done to help Iraq’s most vulnerable people.

“With drought conditions expected to continue and even worsen, farming communities are at risk of further crop failure, which could result in more displacement if action is not taken,” Zullo told Arab News.

As the dry season gives way to warmer weather, however, it is very likely that Iraqis will be more hungry and thirsty this summer than ever before.