JEDDAH: Charity is part and parcel of Ramadan for any Muslim who can afford to donate to the needy. In fact, zakat, as it is known, is one of the five pillars of Islam.

However, this spirit of generosity is all too often exploited by criminals who mobilize women, children, the elderly and the disabled to enrich themselves.

In Saudi Arabia, the government has responded to the problem by launching a number of state-regulated charity platforms as well as public-awareness drives whose objective is to prevent such exploitation and ensure that donations do not end up financing terrorism.

Well-meaning donors are discouraged from shelling out money that could end up financing terrorist activities. (Supplied)

The Kingdom’s Presidency of State Security recently launched a powerful social-media campaign featuring a video in which a woman coerces three children to beg in the streets.

When a passer-by hands the women money, she places it in her shirt pocket, exposing an assault rifle and a suicide vest hidden beneath her black garb.

The woman then removes her veil to reveal she is in fact a man in disguise. The message is simple: “Donating to unknown individuals increases the possibility of terrorist financing.”

Saudi Arabia introduced a new anti-beggary law in 2021. Under its provisions, anyone who engages in begging, incites begging or helps begging in any way can face up to six months in jail, a fine of SR50,000 ($13,329), or both.

Culprits within an organized group that engages in begging, meanwhile, can face up to a year in jail, a fine of $26,659, or both.

Under the anti-begging law, anyone who asks for money directly or indirectly, fakes injuries or disabilities, or uses children to influence others into giving them money is considered a beggar.

Non-Saudi offenders can be deported after serving their sentence and can be banned from re-entering the Kingdom. A newly revised statute also considered begging through social-media platforms to be equal to traditional begging.

While there are genuinely needy people in the relatively affluent Arab Gulf countries who beg during the holy month of Ramadan, criminal groups have been known to run elaborate syndicates, trafficking vulnerable people into Saudi Arabia to collect money on their behalf.

Non-Saudi offenders of the anti-begging law can be deported after serving their sentence. (SPA file photo)

Ali, a Yemeni boy who claims to be 12-years-old but looks much younger, spends his days with two other boys of a similar age begging and cleaning car windshields on one of Jeddah’s main bridges.

“I came less than a year ago,” Ali told Arab News, squeegee and soap bottle in hand on the busy roadside. “I just want to help my family. I can’t go home now without making any money. I have a family. Please help.”

On a nearby street corner, elderly men and women in wheelchairs wait for passing motorists to stop to give them food or money, clutching papers claiming they cannot afford their medical expenses.

At the traffic lights, disheveled children holding infants on their hips tap on the windows of passing vehicles, open palms upturned begging for loose change.

The sight is familiar throughout the Middle East. But even the most trusting of people can be left with the nagging doubt: Where does the money go? Could this scene, which never fails to tug at the heartstrings, have been staged by an unseen handler? Are the motorists only fueling the problem by handing out cash?

Well-meaning donors are discouraged from shelling out money that could end up financing terrorist activities. (Supplied)

The Kingdom’s countermeasures are not confined to street-level begging. Saudi authorities have for some time focused on combating criminal gangs and extremist groups fraudulently posing as legitimate charitable organizations.

In 2016, the Interior Ministry said that it was illegal for organizations to raise funds without first obtaining a permit from the relevant authorities.

Charitable organizations have also been called on to become more transparent about how they collect and use public donations. The government’s own digitalization drive has greatly improved transparency and increased efficiency in the delivery of e-services.

The digital transformation is expanding in the charitable sector with the creation of new regulated services, including Ehsan, Shefaa, KSrelief, and the National Donations Platform, developed and supervised by the Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority.

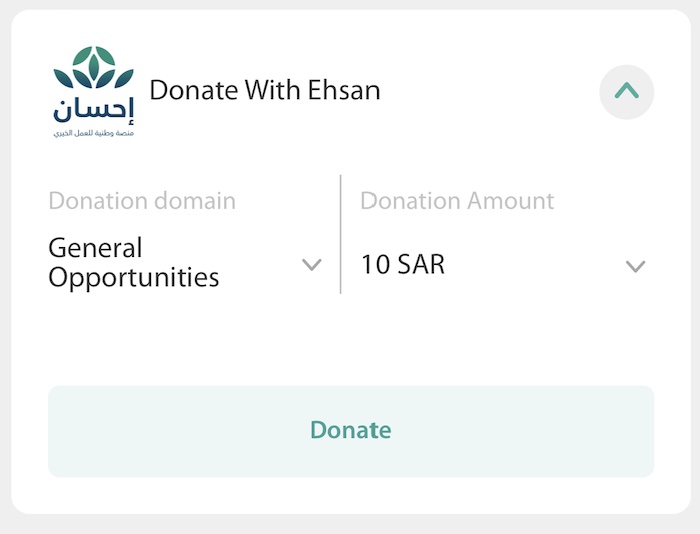

Ehsan, a platform launched in 2021, enables philanthropists and donors to choose from a selection of charitable causes that they deem close to their heart, from social and economic issues, to health, education and the environment.

By focusing on individual values and specific societal issues, Ehsan aims to encourage a greater sense of social responsibility among the general public and private-sector organizations, while also promoting a culture of transparency in charitable giving.

INNUMBERS

$1.4 billion - Donations made through the KSrelief platform.

$386.5 million - Donations through the Ehsan platform.

$25.9 million - Donations through the Shefaa platform.

One of Ehsan’s services, the Furijat initiative, is a debt-repayment scheme for people convicted of financial crimes who are released from prison once their debt is paid off. Another initiative called Tyassarat helps debt-burdened citizens to rearrange their finances and get back on track.

Donors using the Ehsan platform can choose how much they would like to give and can pay by debit or credit card or with Apple Pay.

Donations became even easier in early February this year through the Tawakkalna smartphone app, the official Saudi Contact Tracing service launched to trace the spread of COVID-19.

Last year, King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman made multiple donations via Ehsan that pushed the platform’s total figure past the SR1 billion mark. Since its launch, Ehsan has received more than SR1.4 billion ($373.2 million) in donations and handed them out to more than 4.3 million beneficiaries.

On Wednesday King Salman approved the launch — for the second year in a row — of the National Campaign for Charitable Work through the Ehsan platform.

The National Donations Platform likewise provides easy solutions to connect donors with needy individuals across the Kingdom, while ensuring a reliable and secure digital donation process supervised by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development.

To date, more than 3.5 million people have benefited from money gifted through the National Donations Platform, including orphans, the sick, the elderly and people living in substandard housing.

Those wishing to contribute to overseas aid projects can do so through the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center, KSRelief, which works in 79 countries, supporting everything from the provision of specialist surgeries to landmine clearance.

Saudi Arabia's KSrelief distributed 1,800 Ramadan food baskets in the Sindh province of Pakistan, benefiting 12,600 individuals. (SPA)

As of February this year, $5.6 billion has been spent on the implementation of some 1,919 projects, many of them relating to food security and public health campaigns. Yemen, Palestine and Syria are its top three beneficiaries.

With many Arab countries struggling to overcome the economic blows of the COVID-19 pandemic and the inflationary impact of the war in Ukraine on food and fuel prices, charitable donations are needed now more than ever to support those in need.

Fortunately, public outpourings of generosity, even before the holy month of Ramadan, have allowed aid agencies in the Kingdom and beyond to provide relief where it is needed most.

By regulating donations and ensuring transparency, Saudi authorities can now ensure this assistance does not end up lining the pockets of criminals or funding acts of terrorism but instead reaches those who are genuinely in need.