DUBAI: As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine enters its fourth week, any lingering fondness that Ukrainians may have had for shared bonds of kinship and culture is hard to come by. The overwhelming feeling now seems to be a blend of anger, resentment and bitterness that is likely to last generations.

Underlying the current attempt to bring Ukraine back into the fold of Russia appears to be the conviction that the two peoples are one and the same — the product of a shared history spanning centuries.

The Kremlin has said its “special military operation” is aimed at protecting Russia’s security and that of Russian-speaking people in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region.

However, for many Ukrainians, particularly those who came of age after 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine declared independence, the invasion has only served to accentuate the ethnic, political, and cultural differences between Russia and Ukraine at the expense of their commonalities.

“My paternal grandparents are from Ukraine,” Eugene B. Kogan, a researcher at Harvard Business School who emigrated to the US from Russia in the 1990s, told Arab News. “The unexpected effect of this war is that I have a renewed interest in understanding where my ancestors came from and in my family history.”

Far from drawing Russians and Ukrainians closer, the invasion, which started on Feb. 24, appears to have driven a deeper wedge between the two peoples, while fanning the flames of Ukrainian nationalism and cementing further the political and defense ties that bind Ukraine to Western Europe.

Regardless of the seething bitterness, indeed hate, that consumes many Ukrainians as their cities are pulverized by the Russian military, the two peoples share undeniable bonds, linked by a common thread of history in everything from religion and written script to politics, geography, social customs, and cuisine.

In a recent opinion piece in The Guardian, Alex Halberstadt, author of “Young Heroes of the Soviet Union,” said: “Ukrainians and Russians share much of their culture and history, and an estimated 11 million Russians have Ukrainian relatives. Millions more have Ukrainian spouses and friends.”

Both nations, alongside Belarus, can trace their cultural ancestry back to the medieval kingdom of Kievan Rus, whose 9th century Prince Vladimir I, the Grand Duke of Kyiv, was baptized in Crimea after rejecting paganism, becoming the first Christian ruler of all Russia. In fact, in 2014, when Russian President Vladimir Putin annexed Crimea, he cited this moment in history to help justify his actions.

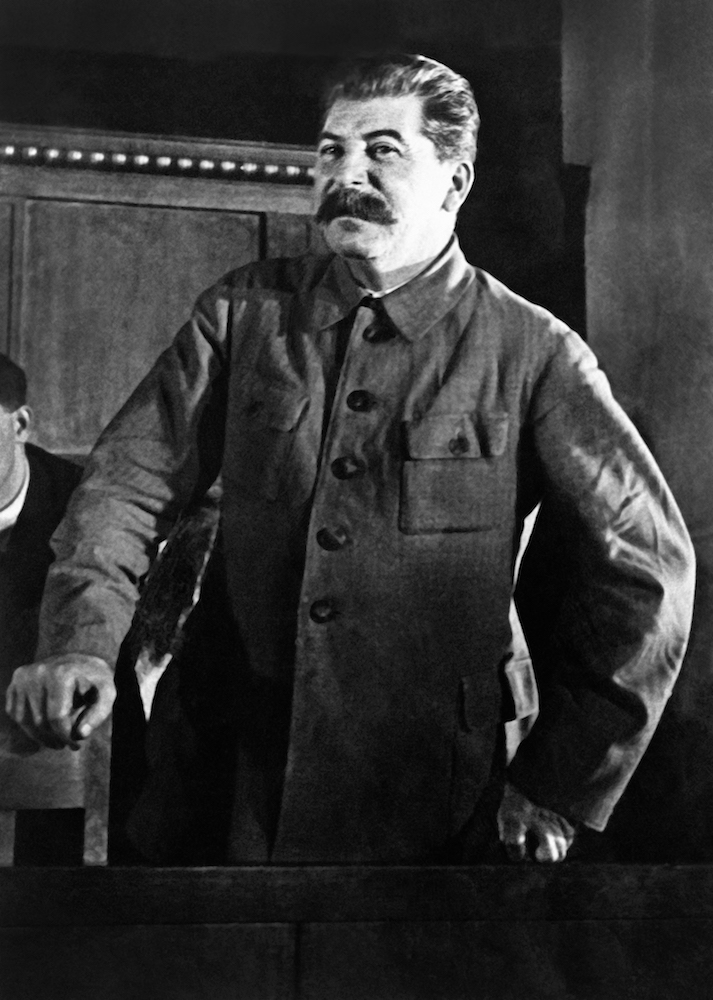

The former dictator of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin. (AFP)

Religious identity has played a part in the justification of the war on the grounds of defending the Moscow-oriented Orthodox Christian population of Ukraine, who are divided between an independent-minded group based in Kyiv and another loyal to its patriarch in Moscow.

Leaders of both Ukrainian Orthodox communities, however, have fiercely denounced the invasion, as have Ukraine’s significant Catholic minority.

Another factor is demographics. When Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, a policy of Ukrainian out-bound and Russian in-bound migration saw the ethnic Ukrainian share of the population decline from 77 percent in 1959 to 73 percent in 1991.

Upon Ukraine’s independence, however, this trend was thrown into reverse. By the turn of the 21st century, Ukrainians made up more than three-quarters of the population, while Russians made up the largest minority.

Modern Ukraine shows influences of many other cultures in the post-Soviet neighborhood — not just Russia. Prior to its incorporation into the Soviet Union, the country was subject to long periods of domination by Poland and Lithuania. It enjoyed a brief bout of independence between 1918 and 1920, during which several of its border regions were controlled by Romania, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, all of which left their mark.

We always thought of ourselves as brothers and sisters. We have so much shared history and to see what is happening is even more heartbreaking because of that.

The Russian and Ukrainian languages, while both stemming from the same branch of the Slavic language family, have their own distinct features. The Ukrainian language shares many similarities with Polish.

Although Russian is the most widely spoken minority language in Ukraine, a significant number of people in the country also speak Yiddish, Polish, Belarusian, Romanian, Moldovan, Bulgarian, Crimean Turkish, and Hungarian.

Russia has left an indelible mark, nonetheless. During both the tsarist and the Soviet periods, Russian was the common language of government administration and public life in Ukraine, with the native tongue of the local population reduced to a secondary status.

In the decade after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, the Ukrainian language was initially afforded equal status with Russian. But, during the 1930s, a policy of Russification was implemented, and it was only in 1989 that Ukrainian became the country’s official language once again, its status confirmed in the 1996 constitution.

Many of the present-day commonalities between the two cultures are actually the result of long spells of Russification, first under the Romanovs and later under Joseph Stalin when the Soviet dictator unleashed his disastrous collectivization policy on the Ukrainian population.

While Ukraine enjoyed a brief period of independence from the end of the First World War in 1918 until 1920, for much of its history it has been a junior partner in its own existence — despite this, many Ukrainians and Russians have familial ties to each other, with close cultural and linguistic bonds. (Getty Images)

Nadia Kaabi-Linke, a Ukrainian-Arab artist based in Berlin, was due to open a solo exhibition at the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv on March 4 but is now back in Berlin helping Ukrainian refugees.

She told Arab News: “I would not put the relationship between Ukraine and Russia in terms of similarities right now because, after the invasion, many things have changed in my mind and in the core of my own being.

“I have started to question my mother tongue — my Ukrainian mother spoke to me in Russian — and I never did before. I even speak Russian to my two children.

“I will not discuss differences and similarities, but I will put it in a way that I might not have ever done before the invasion. Now I feel it is fitting to say this is colonization,” she said.

Unsurprisingly, it is not just people with Ukrainian heritage who feel that the rhetoric of nationalism has poisoned a once close relationship, pulling the two peoples apart.

A body covered with a blanket lies among damages in a residential area after shelling in Kyiv on March 18, 2022, as Russian troops try to encircle the Ukrainian capital. (AFP)

Russian-born Tanya Kronfli, who has lived in the Gulf for nearly 10 years, told Arab News: “I feel heartbroken, sad, angry, and helpless. We always thought of each other as brothers and sisters. We have so much shared history and to see what is happening is even more heartbreaking because of that.”

Kronfli pointed out that Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians were “from different countries but are the same people. Our languages are nearly the same and many families have intermarried. It’s such a mix with many similarities.”

The Kremlin has repeatedly said that NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe and Ukraine’s ambition to join the alliance created a security dilemma for Russia. It has continued to demand Ukraine’s disarmament and guarantees that it would never join NATO — conditions that Kyiv and NATO have ruled out.

Kogan said: “Another security analysis is that the Kremlin felt uneasy with Ukrainians’ Westward leanings and democratic aspirations, thanks lately to the efforts of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

“Past color revolutions (Georgia in 2003, Ukraine 2004, Kyrgyzstan 2005) and Zelensky’s West-leaning ambitions are of deep concern to the Kremlin’s sense of control over Russia’s near abroad.”

Intent on halting Ukraine’s drift to the West, Moscow has rejected the idea of Ukrainian national identity, saying that Russia’s Ukrainian brothers and sisters have been taken hostage by a Western-backed Nazi cabal, and that Russian troops would be welcomed as liberators.

A Ukrainian policeman secures the area by a five-storey residential building that partially collapsed after a shelling in Kyiv. (AFP)

“One often-heard argument is that the post-Soviet Russian leadership never accepted Ukraine as a nation and Ukrainians as a separate people requiring a geopolitically viable nation state in the international system,” Kogan added.

In a speech just days before the invasion began, Putin defended his formal recognition of the breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics by declaring that Ukraine was an invention of Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, who he said had wrongly endowed Ukraine with a sense of statehood by allowing it to enjoy autonomy within the Soviet Union.

“Modern Ukraine was entirely and fully created by Russia, more specifically the Bolshevik, communist Russia,” Putin said in a televised address.

“This process began practically immediately after the 1917 revolution, and moreover Lenin and his associates did it in the sloppiest way in relation to Russia — by dividing, tearing from her pieces of her own historical territory.”

It remains unclear whether all Russians believe this interpretation of history or consider it a plausible moral justification for the invasion.

It is true that through wars, disasters, and Soviet tyranny, Russians and Ukrainians, living side by side as neighbors or compatriots, managed to preserve their kinship.

Nevertheless, for many Ukrainians, their distinctive history, identity, and sovereign right to choose their own destiny are evidently not matters open to debate.