ABU DHABI: As Kosovo celebrates its 14th independence day, Europe’s newest country — and one with the continent’s youngest population — has much to be proud of. More than 100 countries have recognized Kosovo since it declared its independence from Serbia on Feb. 17, 2008.

Despite a high government turnover rate, Kosovo continues to be a robust democracy with a dense network of nongovernmental institutions and civil society groups. It has a resilient economy, a capable leadership and excellent relations with the EU, US and the Gulf countries.

Still, much remains to be done. Getting Kosovo fully engaged and integrated into the region and European and Euro-Atlantic institutions is a work in progress. Relations with its neighbors Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina are far from normalized. As for Russia, China and the five EU members that do not recognize Kosovo’s statehood, there is no sign yet of any change in their attitude.

Fortunately for Kosovo, the people who currently hold the two highest offices in the land — Albin Kurti and Vjosa Osmani — cut their political teeth on the issue of corruption. Since late March 2021, politics in Kosovo has been shaped jointly by movements launched respectively by Kurti and Osmani, Guxo and Vetevendosja.

Kurti is the country’s sixth prime minister while Osmani is the fifth elected head of state. Both are seen as untainted politicians with no wartime baggage, having clear visions for the country, and unafraid to spell out their positions on matters involving Kosovo’s allies as well as adversaries.

They also have no illusions about the tasks at hand. Both regionally and internally, Kosovo is faced with major challenges. Unless its domestic problems are tackled as a matter of priority, the country’s dream of standing on its feet and boosting its chances to integrate into the EU, which Kosovars strongly desire, will remain unfulfilled.

Topping the list is the endemic corruption in both the government and the private sector. The mere perception of corruption being tackled would spur foreign investment, as investors avoid countries where corruption is widespread and palms have to be greased at every level.

In a 2021 report by the UNDP, Kosovo Serbs listed unemployment, personal safety and urban development as their top three concerns. For other ethnic groups, poverty and regular access to electricity were the top priorities for the foreseeable future.

On the bright side, all ethnic groups agreed that the legislative, executive and judicial branches of the government had become more efficient and less corrupt.

READ MORE

Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti spoke exclusively to Arab News in a wide-ranging interview to mark the 14th Independence Day of his country. From NATO to relations with Gulf nations, read the full interview here.

Then there is the need for faster economic development, given the persistently high levels of poverty and unemployment, insufficient domestic and foreign investment, and problems in the business environment.

Another domestic challenge for the Kosovo government is the protection of human rights, regardless of people’s ethnicity, religion, political beliefs and orientation. Treating all citizens as equal before the law in both theory and practice will undoubtedly improve Kosovo’s chances of integration into the EU.

Kosovo’s secular democratic foundation cannot be taken for granted in view of the threats presented by authoritarian leaders in such EU countries as Poland and Hungary. Keeping religion out of civilian affairs is just as important as preserving free and fair elections, freedom of the press and assembly, and a judiciary free of political influence.

Kosovo faced a long rebuilding process after the destruction of the war, but the country is now eyeing EU accession as its political confidence grows. (Shutterstock)

EU integration could well be the best catalyst for transforming the socio-political and economic conditions in Kosovo. But the road so far has proved rockier than predicted.

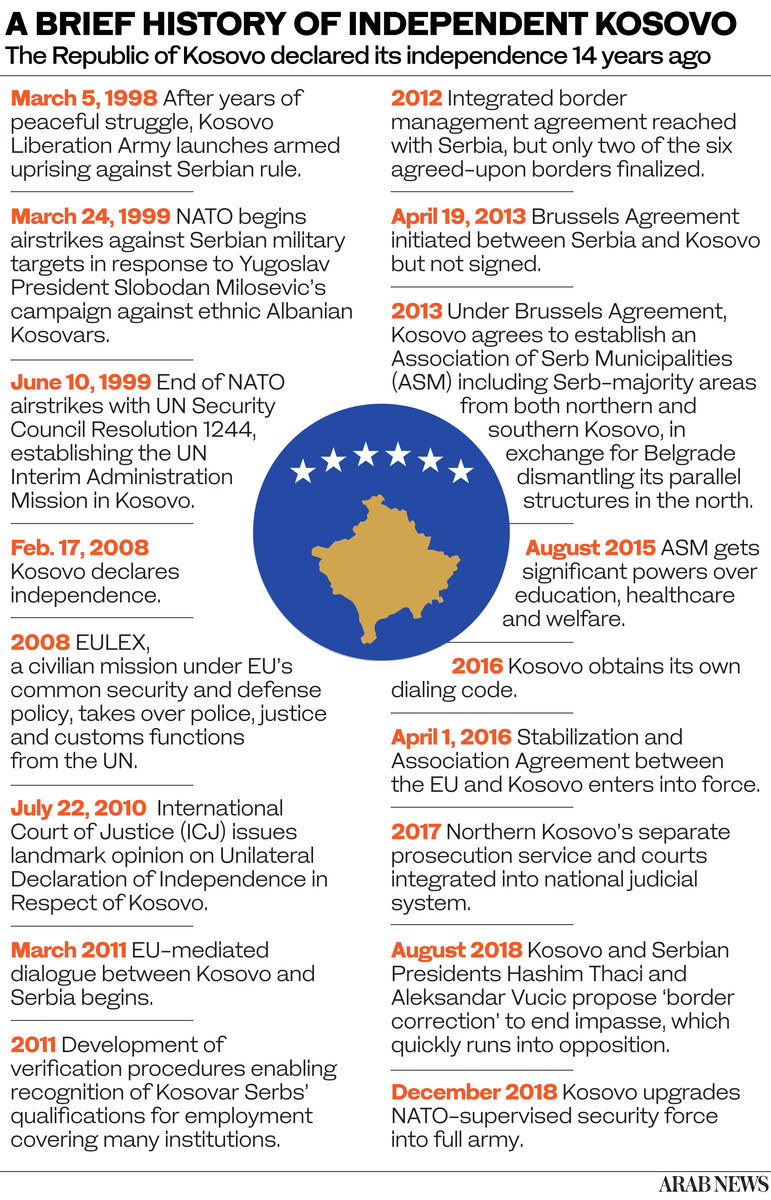

In 2016, Kosovo signed the Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU, marking the most significant milestone in its history toward European integration. Two years later, the European Commission published its expansion plan for the Union’s post-2025 enlargement, including Kosovo and five of its neighbors — Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia.

The road to EU integration for Kosovo has so far has proved rockier than predicted. (AFP file photo)

In 2020, Kosovo lifted its 100 percent tariff on imports from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, a move that enabled restoration of trade with Serbia and Bosnia and the resumption of the EU-facilitated Belgrade-Pristina dialogue. However, Kosovo’s pursuit of EU membership has come to grief mainly over Serbia’s refusal to recognize its independence.

Serbia, which sees Kosovo as its own territory, continues to canvass countries to withdraw their recognition of Kosovo’s independence, although two former Yugoslav republics have defied such pressure: Macedonia (now the Republic of North Macedonia), which became a member of NATO in 2020, and Montenegro.

One of the main obstacles to normalization of relations with Serbia is the status of Serbs in Kosovo (Eastern Orthodox Christians comprise 84.5 percent of Serbia’s population while 95.6 percent of Kosovo’s population are Muslims, most of them ethnic Albanians).

READ MORE

Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti condemned the continuing series of Houthi attacks on civilian targets in Saudi Arabia, and more recently the UAE, agreeing that such assaults reveal the Houthis to be a terrorist group. Read more here.

For the past two decades, Mitrovica in northern Kosovo has straddled a fault line between Serbs in the north and ethnic Albanians in the south.

The Serbs in Mitrovica and other northern enclaves have doggedly refused to acknowledge Kosovo’s independence. Before 1999, the city’s residents lived in mixed neighborhoods, but in the years following the war, the deep divisions separating Albanians and Serbs have solidified, leaving little room for dialogue.

NATO underwrites the fragile peace while the Ibar River effectively partitions the two communities, but EU-brokered on-off talks have yielded little progress over the years.

Prime Minister Kurti has suggested greater synchronization between Washington and Brussels in the Western Balkans while Kosovo works on three goals: Strengthening the rule of law, achieving security through NATO membership and forging greater European unity through Western Balkan membership of the EU.

Prime Minister Albin Kurti reviews Kosovo's honor guard in Pristina. (AFP file photo)

Additionally, Kosovo has time-tested partners in the Middle East who are committed to its independence and wellbeing, with Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the lead. The Kingdom was one of the earliest countries to recognize Kosovo’s independence, one of its main supporters at the International Criminal Court, and a key force behind the OIC’s recognition of its sovereignty in 2009.

One year after the Kosovo War, Saudi Arabia spent at least SR12 million ($3.2 million) in reconstructing houses, schools and mosques. In 2020, Kosovo and Saudi Arabia began the joint implementation of an agreement on avoidance of double taxation.

At a ceremony in Riyadh in January 2020 where Kosovar career diplomat Lulzim Mjeku was among a group of ambassadors who presented their credentials, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman emphasized his willingness to work with each country to enhance and develop bilateral relations.

Kosovar Ambassador Lulzim Mjeku presenting his their credentials to King Salman during a ceremony in Riyadh in January 2020. (Twitter photo)

During Kosovo’s fight against COVID-19, the Muslim World League sent valuable humanitarian assistance. Last year, Kurti thanked the Kingdom’s leadership for its support for Kosovo in all international forums and for providing aid for alleviating human suffering.

More recent talks between the two countries have focused on boosting cooperation in economy, trade, tourism, investment, education, health and infrastructure.

As for the UAE, it joined Nato’s KFOR peacekeepers in 1999, undertaking an aid mission that involved feeding thousands of fleeing refugees on the Albanian border. In collaboration with the Red Crescent, the UAE built a camp that, at its peak, served up to 15,000 people a day.

Members of the NATO-led peacekeepers in Kosovo (KFOR) attend the change of command ceremony in Pristina on Oct. 15, 2021. (AFP)

Almost 1,500 Emirati troops would serve in Kosovo over two operations: One was with KFOR from the spring of 1999 to late 2001. The other operation was the White Hands aid mission across the border, in Albania, between March and late June 1999.

The Gulf countries’ close rapport with the countries of the Western Balkans holds the promise of facilitating the normalization of relations between Kosovo and all its neighbors, and unlocking the region’s full human and economic potential.

As Kosovo’s ties with Arab countries evolve from being centered around humanitarianism and reconstruction to political, economic and security cooperation, the transformation could well have a salutary effect on its relations with Serbia, too.