DUBAI: In the spring of 1893, the German diplomat and archaeologist Max von Oppenheim embarked on an expedition from Damascus to Basra. The journey would take him through the Syrian desert and south through Mesopotamia to the Arabian Gulf. In total, he would travel more than 1,200 kilometers.

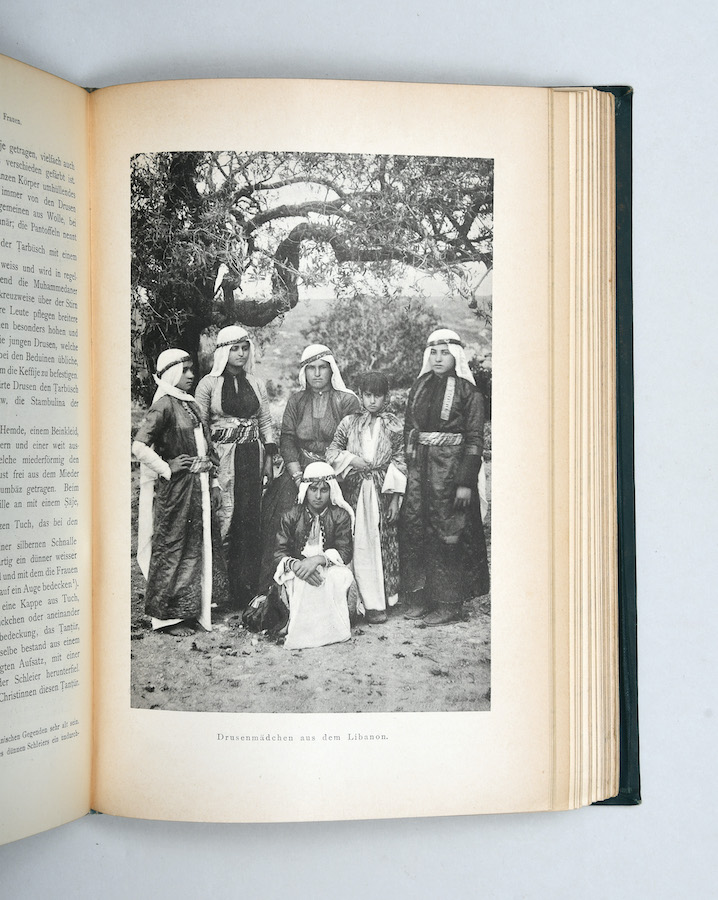

Along the way, Oppenheim kept a meticulous record of everything he saw. He took photographs, mapped the landscape, collected material on the Bedouin, and built up biographical portraits of the people he encountered. He would later say: “In the course of this expedition, I came to love the wild, unconstrained life of the sons of the desert.”

Oppenheim’s record of his journey would lead to the publication of “Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf,” a two-volume account of his travels through the Hauran (southern Syria and northern Jordan), the Syrian desert, and modern-day Iraq. A remarkable historical document, the first edition was published between 1899 and 1900 by Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen) and has remained a key source for the understanding of the region for 120 years.

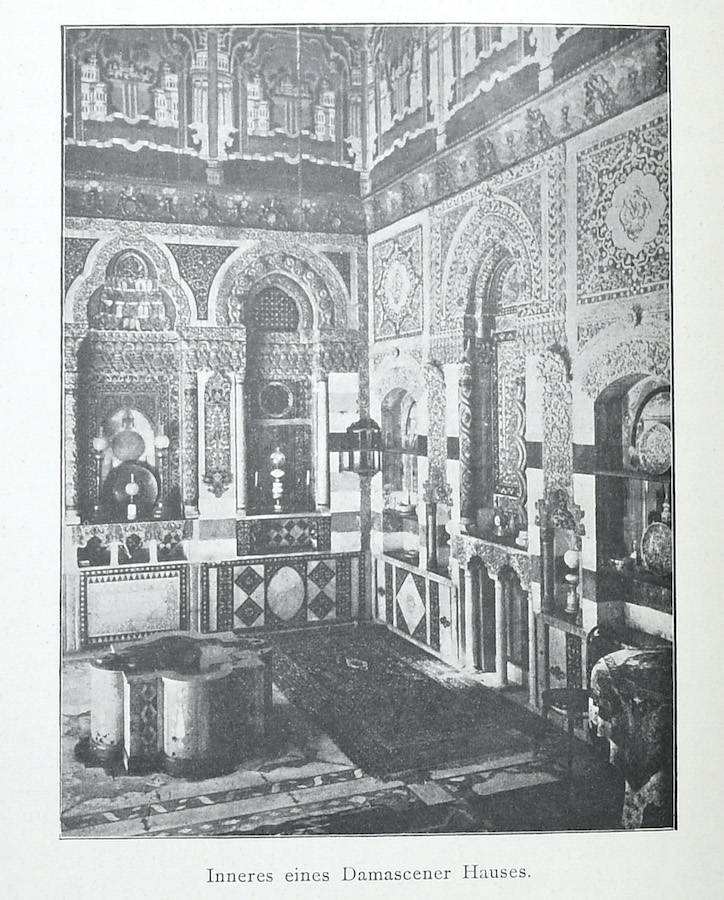

This picture shows the interior of a damascene house. (Supplied)

“Both the book’s remarkably thorough and detailed content and its rarity make it a compelling and sought-after work,” says Duncan McCoshan, a cataloguer at London-based rare book dealer Peter Harrington. “These are very handsomely produced volumes that, for a commercial publication, spared no expense.”

As well as two “genuinely impressive” large folding maps by the German cartographer Richard Kiepert, the work contains a series of stunning photographs, about a third of which are by the renowned German photographer Hermann Burchardt, although he goes uncredited. During the course of his career Oppenheim often took photographs himself, but he also travelled with a team of professionals, including the British film pioneer Robert Paul and the German photographer Waldemar Titzenthaler.

The two volumes — copies of which were brought to the Sharjah International Book Fair by Peter Harrington earlier this month — were printed at a time when publishers were experimenting with various techniques of binding, illustrating and decorating books, says McCoshan. “The results of these innovations can be spectacular, as with this set, when the book survives in sharp condition. However, many of these improvements mean that the book can easily become tired – the lettering and decorative ‘blocking’ can wear off, and the multiple plates bound in tend to weaken the binding, becoming loose.

This picture shows a courtyard of a damascene house. (Supplied)

“This is particularly so in the case of key reference titles like this which came in for quite a lot of serious use over an extended period. Then the superb, highly detailed maps are loose in pockets, so that they can be removed, laid out flat and studied closely; and maybe borrowed and perhaps never returned. It is far from common in any condition, but to find it bright, tight, and complete as it is here is very unusual indeed.”

Despite the value of his work, Oppenheim was a controversial figure. He had originally trained as a lawyer, held various consular and diplomatic postings, and later became an archaeologist. Arguably his greatest archaeological achievement would be the discovery and excavation of the Neolithic site of Tell Halaf in north-eastern Syria.

But behind this public persona lay “a rather shadowy figure” who moved through the region as “an adventurer for German imperial ambition.”

Oppenheim’s record of his journey would lead to the publication of “Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf,” a two-volume account of his travels through the Hauran, the Syrian desert, and modern-day Iraq. (Supplied)

As McCoshan explains, Oppenheim used “archaeology and anthropology as a cover for an attempt to undermine British prestige, much as Lawrence of Arabia was doing on the other side of the coin.” As a consequence, he was known to British intelligence as ‘the Kaiser’s spy.’

“He was seen by the Allied Powers of the First World War as the chief instigator and organizer of jihad, the intention of which was to destabilize the region and draw in troops from Britain and France,” says McCoshan, who first encountered Oppenheim through the works of the British author and historian Peter Hopkirk. “We know about it because British intelligence in the region was always highly suspicious of his activities.”

This is a picture of Druze women in Lebanon. (Supplied)

In 1899, Oppenheim embarked on another journey, this time from Cairo via Aleppo to Damascus and northern Mesopotamia. Ostensibly an expedition to determine possible routes for the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway, of which Deutsche Bank was a primary sponsor, his covert mission was the dissemination of anti-British propaganda and the undermining of British prestige. It was during this trip that he discovered Tell Halaf.

“Oppenheim’s book brings to life the geo-political importance of the region and deepens our understanding of it at the turn of the 20th century,” says McCoshan. Something he achieved “through his painstaking research, his bravura investigations, and his conspicuous sympathy for the peoples of the region, in particular the Bedouin.”